Whitecross Street Debtors' Prison, City of London

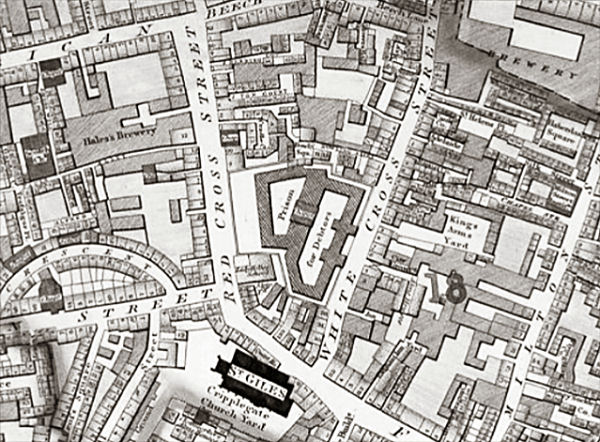

Whitecross Street Debtors' Prison was erected in 1813-15 at the east side of the southern end of Whitecross Street, where the Barbican Centre now stands. When it opened all the debtor inmates from Ludgate, Giltspur Street and Newgate prisons were transferred there.

In 1850, Hepworth Dixon wrote of the prison:

Whitecross-street is entirely a debtors' prison. It has never been a place of confinement for criminals. This is observable in the character of the building, as well as in the characters of its inmates. There is no work of any kind going forward. No attempt to offer or afford the unfortunates any sort of instruction is visible. Many of them, of course, do not need it; and others, who do, would not avail themselves of the privilege, if it were held out to them. But probably numbers would. There is, however, a religious service once a-day, and twice on a Sunday.

Whitecross-street prison is divided into six distinct divisions, or wards, respectively called,—1. the Middlesex ward; 2. the Poultry and Giltspur-street ward; 3. the Ludgate ward; 4. the Dietary ward; 5. the Remand ward; 6. the Female ward. These wards are quite separate, and no communication is permitted between the inmates of one and another. The establishment is capable of holding 500 persons. It is, however, very seldom that half that number is confined at one time within its walls. At this period last year it had 147 inmates; tho pressure of the times has since considerably increased the sum-total. There are now 205, of which number 8 are females. The population of this prison is, moreover, very migratory. Last year there were no less than 1,143 commitment — a part of the building having been set apart for persons committed under that act. Many debtors are now sent hither for a fixed term, mostly ten days, at the expiration of which they are discharged. This punishment is principally inflicted for contempt of court. A woman was recently locked up here for ten days, for contempt, because unable or unwilling to discharge a debt of sevenpence! In all such cases, a more penal discipline is enforced. The person incarcerated is not allowed to maintain him or herself, but is compelled to accept the county allowance. However, as the prison diet is good and plentiful, this is no very great hardship; and as their terms of confinement are always short, these are not the most unfortunate of the inmates of Whitecross-street.

Now let us enter the first or Middlesex ward. It is appropriated to the use of debtors from the county — whence its name — but not from the city; and this being a very large constituency, it can boast a very considerable and diversified number of representatives. We come suddenly into a spacious yard, flagged, clean, and airy —considering the dense part of the city in which the prison stands. It is now visiting hour (10 to 1, or 2 to 4), and the yard is consequently crowded. Within the visiting hours any person can enter the gaol to see his friends and acquaintance without restriction.

Round this yard are the lofty walls of the prison, and the general pile of the prison buildings, several stories high. On one side is a large board, containing a list of the benefactors of this portion of the prison. There are similar benefactions to each ward. Amongst others, one from Nell Gwynne, still periodically distributed in the shape of so many loaves of bread, attracts attention. These donations are now employed in hiring some of the poorer of the prisoners to make the beds, clean the floors, and do other menial offices for the rest Passing through a door in the yard, we enter the day-room of this ward. There are benches and tables down the sides, as in some of the cheap coffee-houses in London; and a large fire at the end, at which each man cooks, or has cooked for him, his victuals. On the wall, a number of pigeon-holes, or small cupboards, are placed, each man having the key of one, and keeping therein his bread and butter, tea and coffee, and so forth. These things are all brought in, and no stint is placed upon the quantity consumed. A man may exist in the prison who has been accustomed to good living, though he cannot live well. All kinds of luxuries are prohibited, as are also spirituous drinks. Each man may have a pint of wine a-day, but not more; and dice, cards, and all other instruments for gaming, are strictly vetoed. Chess, however, is permitted; and to a chosen few the game serves to relieve the tedium of a duresse which has no other time-consuming occupation. This day-room — the best, perhaps, in the whole establishment — is any thing but agreeable. Store-room, cooking-room, sitting-room, dining-room, reading-room, and smoking-room, for about forty to sixty persons — it is necessarily full of many scents, and is all but as foul as the streets of Cologne. Yet every man who is sent hither, answering to the condition of the ward, is compelled to take his share of the crowd and stench. There are no private apartments — no means of getting either quiet or privacy. The gentleman occupies the same day-room and night-room as the vagrant There is no distinction of persons in Whitecross street gaol. The unfortunate soldier, barrister, or merchant, is compelled to eat, herd, and sleep with the lowest vagabonds of his sex. The bed rooms are above, and arranged in long chambers in like manner, sixteen or eighteen in a room.

The bedrooms are all badly ventilated. When the prison is full, it must be horrible to sleep in them. And the water-closets are in a disgraceful condition. The sanitary commission should instantly look to this particular. There is abundance of water: yet, for want of a little machinery, there is only one flushing a-day; sometimes not that. The stench is exceedingly disagreeable, and some of the detenues complain of it very much. The defect might be remedied at an expense of a few shillings, by adopting the apparatus now in use at the Bridewell and at several railway stations, by which the opening and closing of the closet door causes a flush of water to fall into the pan.

The other wards are in general character much like the Middlesex, and the one description will therefore serve for all. We will notice only the differences. The Poultry and Giltspur-street ward is occupied by city debtors who are not freemen: the Ludgate ward by city debtors who are freemen. There are very few in this latter ward — only seven at present; and it is the wealthiest in point of donations. In the Dietary ward are placed those persons who are unable to maintain themselves. Here is the saddest sight of all. Most of these persons are in for very small sums, indeed; and the fact of their accepting the prison diet is the best proof of their poverty. The county allowance is, however, liberal, consisting (for males) of 10 lb. 8oz. of wheaten bread; 1lb. 5oz. of cooked meat, without bone; 2lb. of potatos, cooked; 3 pints of soup; and 14 pints of oatmeal gruel, per week; the total cost of which is 4s. 3d. per head. The females have rather less bread, and cocoa instead of gruel; the cost being 4s. 1d. per head. This ward is full of miserable objects; and the effluvia of tobacco, cooking, and confined air in the day-room are almost overpowering.

The Remand ward is the most strictly kept in the gaol. The inmates are compelled to take the prison diet. Remands, commitments for fixed periods for contempt of court, and fraudulent debtors, are sent hither. The diet is the same as that last described. The female ward is attended by a matron; and the debtors therein have not permission to receive the visits of their male friends or relatives. They may, however, speak with them through an iron grating.

There is nothing like order or discipline in this prison. The inmates do much as they choose. No restraint, except in extraordinary cases of insubordination, is placed upon their acts or conversation. The governor is responsible for their personal safety, but nothing further, except — and he has no authority to deal with them unless their safe custody be imperilled — in extreme cases of unruliness, when he has power to place the refractory party in solitary confinement, in a very cold, unpleasant, underground cell, for forty-eight hours giving him for nourishment only bread and water. This is seldom necessary. The detenues have so much latitude allowed them, that they can have scarcely a wish for more. Letters are sent out for every post. Several copies of the morning journals are taken in, and books are admitted at discretion. There is a workroom in the dietary ward for such as prefer to work at their trades. But very few do so, because it is so difficult to obtain employment from the world without. People do not like to send their work — tailoring, shoemaking, &c. into a gaol; and those who try to support themselves by their prison labour almost always foil, and, after a time, throw themselves on the county allowance

The prison was closed in 1870, and all of the prisoners were removed to the newly built Holloway Prison.

Whitecross Street Debtors' Prison site, City of London, 1851.

Whitecross Street Debtors', City of London.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB. Holdings include: Rules and regulations; Returns as to state of prison and prisoners' health 1815; Plans (1812-1871); Records of Prisoners Names of prisoners in custody of Sheriffs in Debtors' Prison (September 1817); Inquests into deaths of prisoners (1815-39); Return of duties, names and ages of officers.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Has a wide variety of crime and prison records going back to the 1770s, including calendars of prisoners, prison registers and criminal registers.

- Find My Past has digitized many of the National Archives' prison records, including prisoner-of-war records, plus a variety of local records including Manchester, York and Plymouth. More information.

- Prison-related records on

Ancestry UK

include Prison Commission Records, 1770-1951

, and local records from London, Swansea, Gloucesterhire and West Yorkshire. More information.

- The Genealogist also has a number of National Archives' prison records. More information.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.