Bridewell, London

Bridewell was originally a palace built by Henry VIII on the west bank of the River Fleet, and took its name from the holy waters in the area linked with St Bridget or Bride. In 1553, Edward VI handed over the site to the City of London authorities as a 'house of occupation' for idlers, vagrants, and prostitutes. Bridewell was rather different from other penal establishments in being part of the poor relief system rather than the criminal justice system. Its aims were to reform the idle and disorderly, to make them earn their keep, and to deter others from indolence. The costs of running Bridewell were largely met from a tax on local inhabitants rather than fees extracted from the inmates who were mostly penniless.

For the more industrious inmates, productive work was available using materials provided by City merchants. Those who were classed as 'sturdy' (i.e. able-bodied) beggars were required to work, and were fed on a 'thin diet onely sufficing to sustaine them in health'. Repeat offenders could be whipped, and were given hard labour such as beating hemp.

The 1576 Poor Act adopted Bridewell's model and proposed the establishment of a 'house of correction' in each county to deal with the able-bodied poor who refused to work. Every county had at least one bridewell operating by 1630. Houses of correction (also known as bridewells after the original London establishment) were supervised by Justices of the Peace and their costs supported from the local poor rates.

A remarkable scandal occurred in 1602 when the running of Bridewell was placed in the hands of private 'lessees' who were to be paid £300 a year to undertake the task. Within a few months, chaos reigned at the prison. The contractors, whose sole aim was to maximise their profit, had moved into the best rooms in the building and had released most of the pauper inmates. The diet fed to those who remained had declined to the point where many of them had died. They had left prison staff unpaid and had rented out workshops as homes for their relatives and friends. Finally, in collusion with eight prostitutes resident in the prison, they had turned the premises into an upmarket casino, restaurant and brothel. In the company of their glamorously dressed hostesses, patrons dined on a sumptuous repast of 'crabbes, lobsters, artetichoques, pyes and gallons of wyne at a tyme.' Use of the prison's single chambers for further pleasures could then be had upon a payment of two to five shillings. Following an inquiry, the lessees' contract was terminated in October 1602.

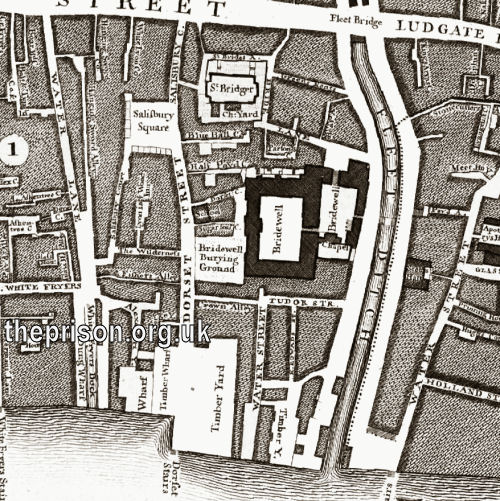

The Bridewell site is shown on the 1746 map below.

Bridewell site, City of London, 1746.

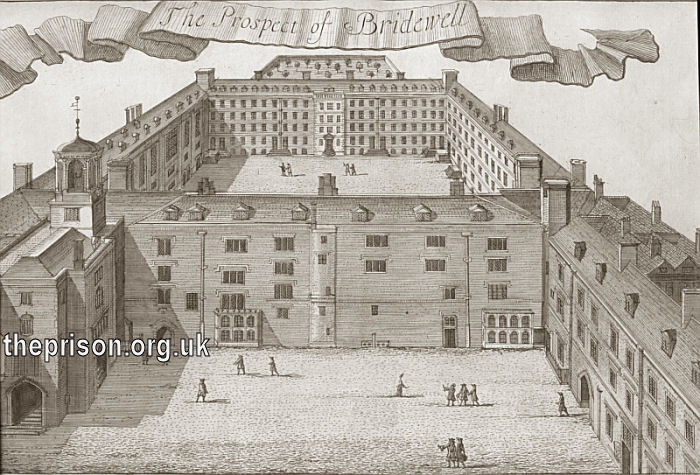

Bird's-eye view of Bridewell, c.1720.

River frontage of Bridewell, c.1660.

In 1777, John Howard reported:

That part of Bridewell which relates to my subject has wards for men and women quite separate. — The men's ward on the ground floor is a day-room in which they beat hemp; and, down a step, their night-room. One of the upper chambers is fitting up for an Infirmary. — The women's ward is a day-room on the ground-floor, in which they beat hemp; and a night-room over it. I was told that the chamber above this is to be fitted up for an Infirmary. The sick have, hitherto, been commonly sent to St. Bartholomew's Hospital. All the Prisoners are kept within doors.

The women's rooms are large, and have opposite windows, for fresh air. Their ward, as well as the men's, has plenty of water: and there is a Hand-Ventilator on the outside, with a tube to each room of the women's ward. This is of great service, when the rooms are crowded with Prisoners, and the weather is warm.

The Prisoners are employed by a Hemp-dresser, who has the profit of their labour, an apartment in the Prison, and a salary of £14. I generally found them at work: they are provided for, so as to be able to perform it. The hours of work are in winter from eight to four; in summer from six to six, deducting meal-times. The Steward is allowed eight-pence a day for the maintenance of each Prisoner; and contracts to supply them as follows — On Sunday, Monday, Tuesday and Thursday, a penny loaf, ten ounces of dressed beef without bone, broth, and three pints of ten shilling beer: on Wednesday, Friday, and Saturday, a penny loaf, four ounces of cheese or some butter, a pint of milk-pottage, and three pints of ten shilling beer.

The Porter or Keeper is John Brown. Salary £80; no Fees. To the women's ward there is a Matron, Sarah Lyon, Salary £60. She takes care of the sick, both men and women; and is allowed a shilling a day for those that are put on the sick diet.

In Bridewell is a Public Chapel: the Prisoners go thither on Sunday morning (except such as are, in a manner, destitute of apparel): the men and women separated from each other, and from the rest of the congregation.

On the walls of the Hall and Court-room are hung up many Tables of very considerable Gifts and Legacies to this Hospital, in common with others: sufficient, one would think, to have made this Prison more commodious, by providing several work-rooms, and lodging-rooms, for keeping the Prisoners more separate.

In winter they have some firing. The night-rooms are supplied with straw, No other Prison in London has any straw or other bedding

In 1789, following a subsequent visit to Bridewell, Howard indicates that conditions in Bridewell were better than in many other prisons;

No alteration but the ventilators taken down. Each sex has a workroom and a night-room. They lie in boxes with a little straw on the floor, The prison not being strong, the men were in irons, some picking oakum, and others were making ropes, which is a new and proper employment. Mr. Hardwick, a hemp-dresser, has their labour, and a salary of twenty guineas a year. Allowance, one penny loaf each, and four days in the week ten ounces of beef without bone, &c. The allowance for persons constantly employed, is not too much, but would it not be better if they had less meat and more bread? The prison wants white-washing, and the men's night-room more light and air. At my first visit two men were in the infirmary; at my last, only one.

There are many excellent regulations in this establishment. The prisoners have a liberal allowance, suitable employment, and some proper instruction; but the visitor laments that they are not more separated.

Inmates: 1787, November 6, Men, 26; women, 25. 1788, September 13, Men, 19; women, 10.

A rather more negative view of Bridewell was presented by Hepworth Dixon in 1850:

As a House of Correction for criminals it could hardly be worse. The building itself is bad, and as it stands upon a cold damp soil, it is far from healthy. In wet weather the doors have water trickling down them, and the air is quite humid. Then the prisoners' apartments are small and straggling. There is a small room here and another there, the whole so ill arranged that no sort of superintendence, worthy of the name, can possibly be maintained. Each talks and does what seemeth good in his own judgment

The cells and corridors are confined and dark: both light and air are admitted in very insufficient quantities for the purposes of health. All these faults characterized the Bridewell when it was inspected by Howard, and they will continue to characterize it so long as the present building stands. No alteration short of absolute re-erection could nuke it a good prison; yet, on the other hand, it is not to be classed for a moment with such places as Giltspur-street Compter and Horsemonger-lane Gaol. It is infinitely superior to either of these in one prime respect — indeed it is superior to any gaol in London, except Pentonville and the Middlesex House of Detention, in this: it has separate sleeping apartments for all its inmates. But on the whole, it is a bad specimen of a prison for a civilized country, and ought to be disused for such a purpose.

The number of prisoners is generally about a hundred — of whom thirty will be females. The sentences are mostly for three months' hard labour. The only work enforced here is that of the wheel and oakum picking — the great majority of offenders being placed upon the former. The wheel machinery is erected within the body of the building. It is entered upon from an almost dark corridor, through small iron gates. As you enter this wing of the building from the open court, the prisoners seem to be working in absolute darkness. Peering through the grating, the motion of the wheel and the straining figure of the criminal may be dimly seen. The absence of any human sound — the dull, soughing voice of the wheel, like the agony of drowning men — the dark shadows toiling and treading in a journey which knows no progress, — force on the mind in voluntary sensations of horror and disgust

The system of discipline pursued in the Bridewell is a mere mockery of the silent system. Communication is forbidden during hours of work, but not prevented. The walkers of the wheel are commanded not to talk; but from the straggling nature of the building, and the paucity of prison officers, complete inspection and control are out of the question. And practically they talk just as much as they think proper, as, when at work, only a thin wooden partition separates one from another: nothing less than the presence of a warder could prevent them.

They who are not sentenced to hard labour are confined in the opposite wing of the prison. Under ground are two small, miserable cells — the day rooms of this department They are very cold and damp; consequently fires have to be kept in them, — a circumstance fatal to all discipline. In each of these rooms, at the time of our visit, there were eight or ten prisoners shut up, picking oakum. They were quite alone: that is, no officer was with them in the room. Occasionally they receive a visit; but by far the greater portion of the day they are quite alone, lolling over the fires, and instructing each other in their favourite arts. How different this to the work rooms of Millbank or Coldbath-fields!

There is no school in this prison. This is the fitting climax of its other faults — the crowning absurdity of the whole system of mismanagement If book-teaching be absolutely required anywhere — if it promise to be successful, to operate for good, any where — surely it is here in the Bridewell. Being summary convictions, the inference is, that persons come here to get their initiation into the prison-world. And the fact is so generally. The ill-directed youth of the city who commits his first petty offence is most likely to be sent hither. Upon the impressions which he takes away may depend the entire future of his existence: for good or evil, in a course of reform or a career of guilt, his incarceration in the Bridewell is the starting-point One thinks with pain and sorrow of the education which such a youth must get here now, and of the direction most likely to be given to his energies by the persons he will meet with. Three months' imprisonment here is enough to ruin any child for life. The boy must have powerful elements of good in him who can leave it no worse for ninety days' contact with its contaminations. Instead of subjecting the unfledged criminal to the pollution of unrestrained intercourse with offenders worse than himself, every care should be taken here, upon the threshold of his career, to lead him back from the fatal path into more reputable and honest courses. The negative act is not enough. He should not alone he kept from peril: he should also be put into the way of good. Two means are patent for this purpose — work and teaching. The work should be severe but useful: such as a man, in whom it was sought to foster habits of self-respect, might be asked to do. The instruction should be sound and regular. What the criminal mind wants most is discipline. Formerly there was a school at Bridewell: it has, for unknown reasons, been given up. Fatal mistake!

If anything could atone for the faults of the City Bridewell, it would be the institution attached to it, called the House of Occupation, in St George's-fields. This is, in fact, an industrial school. It has about 200 inmates, half male, half female. It is not a criminal establishment The majority of its scholars have not been in prison; the minority have — in the Bridewell. Children who are idle, unruly, disposed to be troublesome to their parents and to the community, are taken in, educated, and instructed in a trade, and after several years of careful training, are placed in situations, or permitted to go home to their parents, on the latter making proper application. The instruction given to them is sound and practical: the discipline enforced strict but not rigid; and the general result highly successful. The boys are taught trades: at present there is one or more learning each of these useful employments — engineering, painting, tailoring, shoemaking, masonry, brewing, baking, carpentry, rug-making, rope-making. The girls are being taught every species of domestic arts — washing, sewing, cooking, ironing, knitting, &c. Great care is also taken with the education of their minds. They are said to make admirable domestic servants, and very rarely indeed does one turn out ill. They are in great request: there being usually from twelve to twenty applications for servants on the books of the institution. As they are ready, they are put out

From the Bridewell the magistrates have a power of removal to the House of Occupation, and by this change of scene — this removal from old haunts, old comrades, and old temptations, — hundreds of poor boys are placed in a position for becoming useful and productive, instead of dangerous and expensive members of society. Would that we had more such institutions!

Bridewell was finally closed in 1855.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB. Holdings include: Court of Governors minutes (microfilms, 1559-1919); Prison Committee minutes (1775-1802); Prison Sub-Committee minutes (1792-1854); Prisoners' admission or discharge orders (1691-5, 1773, 1846-68); Prisoners' committal books (1809-1916); Weekly returns of prisoners in custody giving name, age, offence and length of sentence 1817-30); Prisoners' character books giving name, age, date, crime and sentence with remarks on prisoner's background and demeanour (1841-1916); Names of City apprentices sent to Bridewell (1837-1916); Inquests into deaths of prisoners (1783-1838).

Bibliography

- Hinkle, William G. A History of Bridewell Prison, 1553-1700 (2006, Edwin Mellen Press)

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- London Lives 1690 to 1800 has digitized Bridewell's 18th century minute books.

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.