Nationalisation

During the 19th century, the government became increasingly involved in the operation of prisons which had previously been a matter for local county and borough authorities.

Millbank Prison

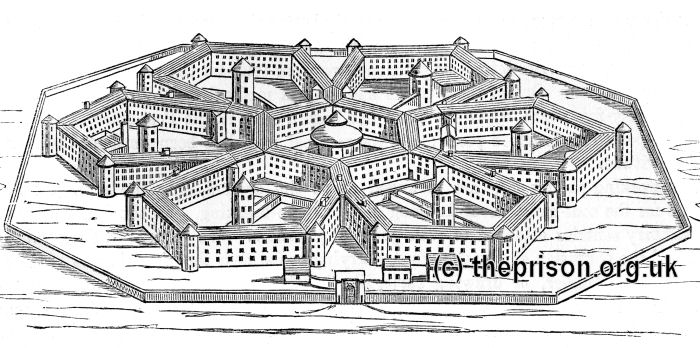

In 1810, there was a revival of a plan to build a new, large, national penitentiary — a scheme that had first been proposed more than thirty years earlier, as a possible solution to the closing of America to transportation. A parliamentary Select Committee decided to recommend the building of a single, large prison for up to 600 inmates — a figure later increased to 1000. The revolutionary design, based on Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon principle, comprised six pentagons, linked to a central hexagon. Construction began in 1812 and was finally completed in 1821. Millbank's regime combined solitary confinement, hard labour, and religious instruction. Despite high hopes, the Millbank scheme was eventually considered a failure and was relegated to use as a holding prison for transportees to Australia, then later as a military prison. More information on Millbank is provided on a separate page.

Millbank Prison, London. © Peter Higginbotham

Prison Inspection

The 1835 Prisons Act further increased central involvement in all the country's prisons. Each prison's rules were now required to be submitted for the Home Secretary's approval, and the Inspectors of Prisons were appointed to visit every establishment at least once a year. The Act also effectively endorsed the use of the 'separate' system of accommodation, with each prisoner housed in a self-contained cell, with virtually no contact with other inmates.

In 1843, under the direction of Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, the Inspectors examined the whole system of prison 'discipline', including such matters as the employment, diet, and health of prisoners, arrangements for their religious instruction and moral improvement, the use of punishments such as the tread-wheel, and the temperature of the cells. As a result of their investigations, a set of regulations was devised to try and bring some consistency to the operation of the 220 or so prisons then operating in England and Wales.

Pentonville Model Prison

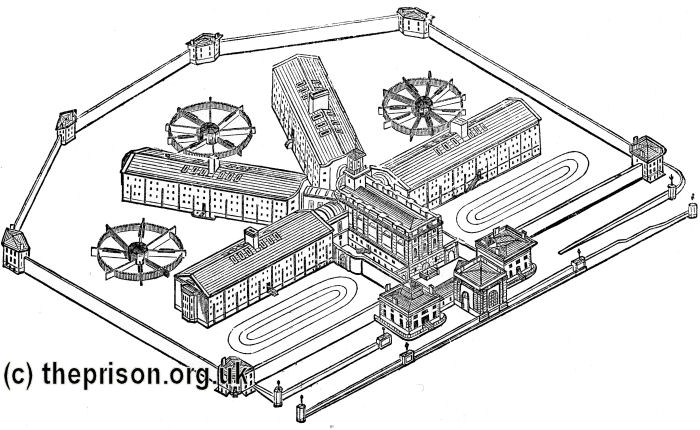

In April 1840, following a proposal by two of the Inspectors of Prisons, construction began of a new model prison at Pentonville, in north London,which was to be run on the separate system. The first inmates arrived in December 1842.

The main prison building comprised a central administration block from which four wings radiated like the spokes of a half-cartwheel. Each wing contained 130 cells arranged in three galleries, one above the other, with each floor containing forty or so individual cells. From the central hall it was possible for staff to have a view of every cell door. Every cell was fitted with an alarm handle which rang a bell and raised a semaphore indicator outside the cell's sound-proof door.

Pentonville Prison, London. © Peter Higginbotham

In addition to its role as a model prison, demonstrating how such an establishing should operate, Pentonville provided an initial term, normally eighteen months, of probationary discipline and labour for selected convicts prior to their transportation to Van Dieman's Land. Those behaving well would receive a ticket-of-leave, effectively freedom in their new country. Those performing indifferently would be given a probationary pass, a status which imposed some restrictions of their movement and earnings. For those whose conduct at Pentonville was deemed unsatisfactory, their destination would be a convict labour settlement.

Public Works Prisons

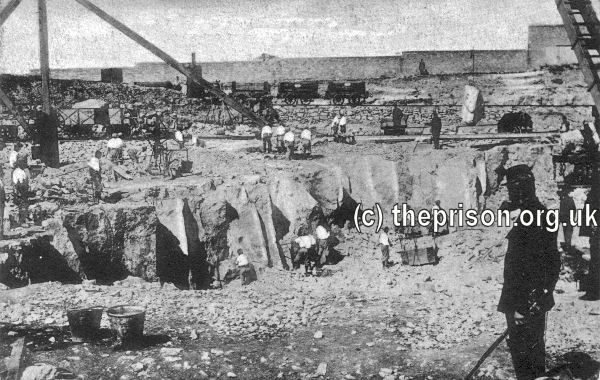

By the 1840s, the decline in the number of available destinations for transporting convicts led to the development of alternative forms of sentence at home. In 1848, a 'public works' prison housing 840 prisoners was opened at Portland in Dorset where the inmates were employed in the local quarries and naval dockyard. A similar but much larger establishment was constructed at Portsmouth in 1852. On Dartmoor, part of the old prisoner-of-war prison — largely empty since 1815 — was put to use as a public-works project, with over a thousand prisoners working on the land, renovating the building, and adapting it to house invalid prisoners.

Quarries at Portland Prison, early 1900s. © Peter Higginbotham

From 1848, those sentenced to between seven and ten years transportation could instead receive twelve months of separate confinement at Pentonville (or Millbank for women), followed by up to three years hard labour at Portland, Dartmoor or on the hulks, with good conduct earning a shorter stay. They would then be transported to Van Diemen's Land or Western Australia, there receiving a pardon so long as they did not return to Britain.

The Directorate of Convict Prisons

By 1850, the involvement of central government in prison provision had grown considerably. As well running prisons at Millbank, Pentonville, Portland, Portsmouth and Dartmoor, the government was renting cells at a number of provincial prisons, including Leeds, Manchester, Leicester, Reading and Wakefield. In order to provide a unified management of government-run prisons, a new body was created, known as the Directorate of Convict Prisons.

Penal Servitude

In 1853, the Penal Servitude Act replaced transportation sentences of less than fourteen years by a shorter sentence of imprisonment in England. A sentence of penal servitude comprised three stages: a period of separate confinement, followed by labour on public works, followed by release on licence. The term 'convict' was applied to those receiving such a sentence.

Nationalisation

The 1865 Prison Act imposed some degree of central control on local prisons, but they were still funded by local rates, with local magistrates playing a part in their administration. The final step in creating a integrated national prison system came with the 1877 Prison Act which placed control of all prisons in the hands of a new body known as the Prison Commissioners. At the same time, the Exchequer took over all the costs of running the prison system.

The nationalisation of the prisons aimed to make the operation of the penal system both uniform and economical. To this end, the Commissioners, chaired by Sir Edmund Du Cane, set about rationalising the country's stock of 113 prisons. In the summer of 1878, 45 were shut down — mostly small town gaols, although eleven county prisons were also closed. The remainder provided space for 24,812 inmates — about 4,000 more than the expected requirements.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.