Millbank Penitentiary, Westminster, London

In 1779, as a possible solution to the end of transportation to America, the British parliament approved a bill for the erection of a pair of 'Penitentiary Houses' (one for 600 men and one for 300 women) on a site near to London. The houses would impose a strict regime with 'labour of the hardest and most servile kind.' The scheme did not come to fruition but an alternative proposal by social reformer Jeremy Bentham, based on the idea of the 'panopticon' or inspection house. The design consisted of a circular or polygonal building with cells on each storey and, at the centre, an inspection 'lodge' from where prisoners could be supervised. Bentham's vigorous and persistent lobbying of ministers eventually resulted in some modest backing for a panopticon prison and in 1799 he acquired a site for its construction on the north bank of the Thames at Millbank. However, like the original Penitentiary Houses project, the scheme never gained sufficient momentum and was effectively abandoned by the government in 1803.

In 1810, more than thirty years after its original conception, the plan to build a new, large, national penitentiary was revived. A parliamentary Select Committee was set up and took evidence from a number of leading figures, including Jeremy Bentham who was still eager to promote the virtues of his panopticon design, but he was effectively sidelined from the project. The Committee decided to recommend construction of a single, large prison for up to 600 convicts — a figure later increased to 1000. A competition for its design took place, the winning plan being submitted by William Williams. The construction work, initially expected to cost in the order of £300,000, began in 1812 at Bentham's own Millbank site. For the land and for all his trouble, Bentham received compensation to the tune of £23,000. Problems with the marshy ground delayed the opening of the prison until 1816 and building was not finally completed until 1821, by which time the cost had risen to the then huge sum of £450,000.

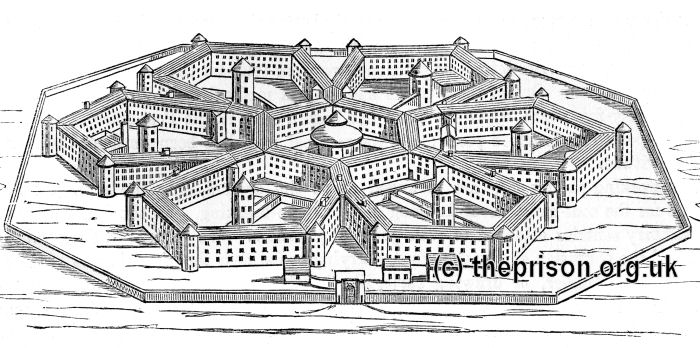

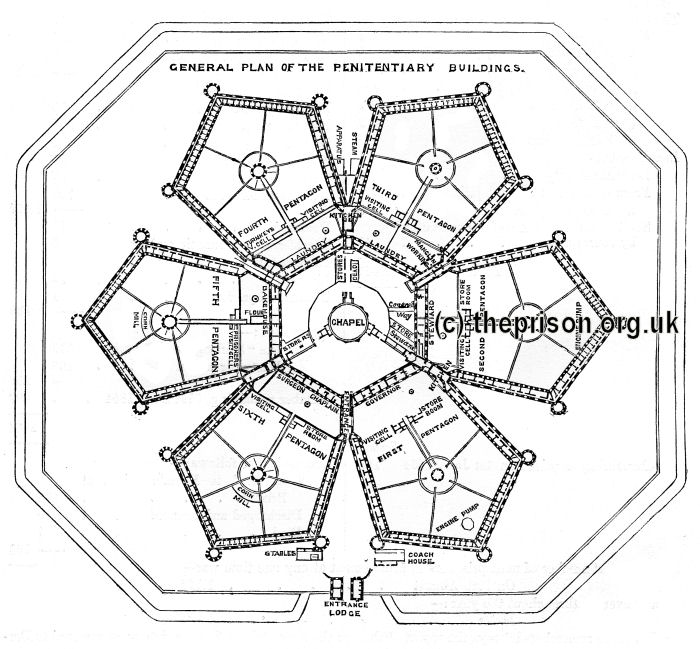

Millbank's novel design revolved around a central hexagon which housed the governor, matron, steward, surgeon, chaplain, master manufacturer, and the bakery. Each of the hexagon's six sides then formed the inner edge of a three-storey pentagonal cell block. The area within each cell block was divided into five airing yards with a tall watch-tower at the centre. Each of the cell blocks was, in effect, a miniature panopticon.

Millbank Prison, London - bird's eye view. © Peter Higginbotham

Millbank Prison, London - plan. © Peter Higginbotham

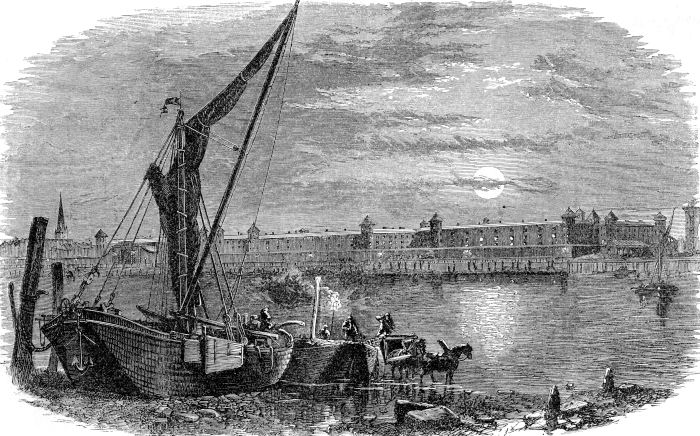

Millbank Penitentiary, London. © Peter Higginbotham

Despite an optimistic start, Millbank was beset by problems. The sheer size of the building, its circular layout, and the labyrinth of winding staircases, dark passages, and innumerable doors and gates proved totally confusing. One old warder, even after several years at the prison, still carried a piece of chalk to help him mark his way around. There were also regular disturbances and even riots. One particularly embarrassing incident took place in April 1818 during a Sunday morning service in the chapel at which the Chancellor of the Exchequer was present. Discontent about recent problems with the prison's bread came to head with male inmates banging the flaps on their seats and throwing loaves around. Some of the women began chants of 'Give us our daily bread' and 'Better bread!' while others began screaming or fainting, and eventually were all escorted from the room. Further unrest was only quelled with the help of the Bow Street Runners.

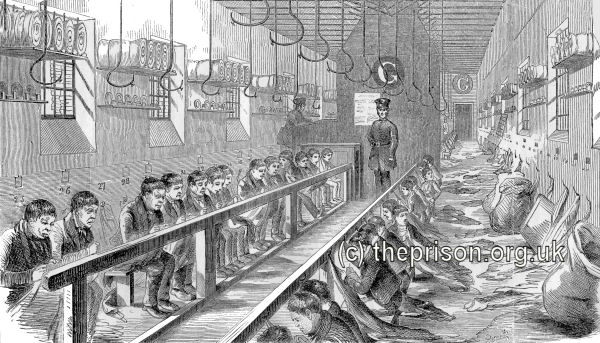

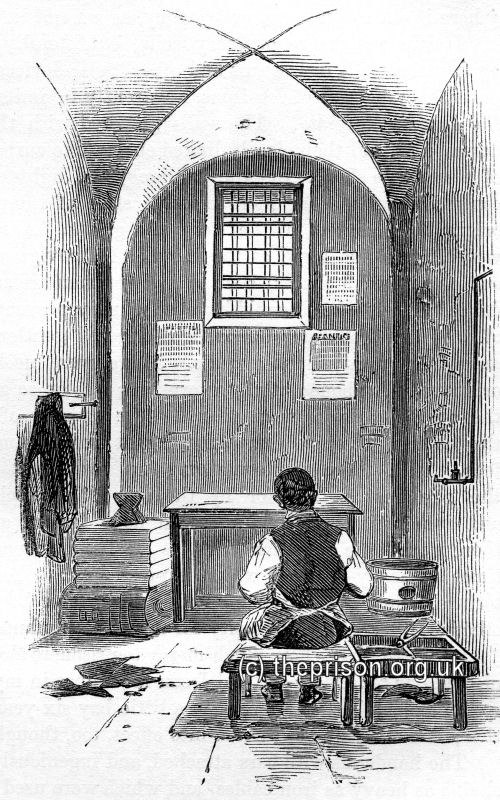

The original regime at Millbank combined elements of the 'separate' and 'silent' system. Those prisoners serving the first half of their sentence (known as First Class inmates) worked and slept in the seclusion of their individual cells. Those in the second half of their sentence (the Second Class) performed their labour in groups. Complete isolation of the First Class inmates proved to be impossible, however — staff were unable to prevent them communicating when they were attending chapel, taking exercise or working a shift on the prison's corn mills or water pumps. It was soon concluded that any beneficial effects of the First Class were rapidly undone in the Second so, from 1832, inmates spent the whole of their sentence in solitude. Even that proved ineffective. Each cell had two doors, an inner one of bars and an outer one of wood. Because of the building's poor ventilation, the outer doors were left open during the day allowing prisoners in adjacent cells to talk to one another.

Millbank Penitentiary, London — workshop under the 'silent; system. © Peter Higginbotham

Millbank Penitentiary, London — prisoner making shoes in his cell. © Peter Higginbotham

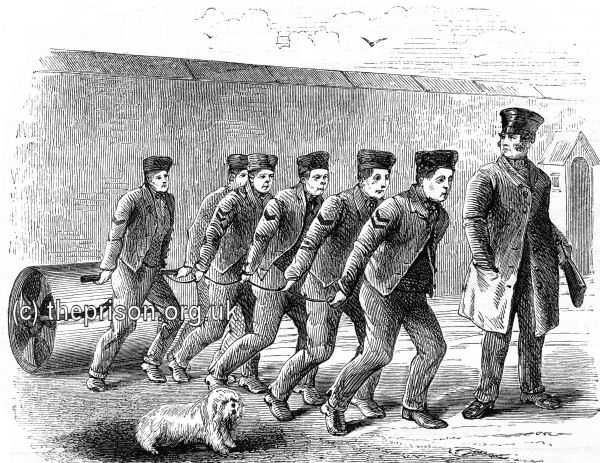

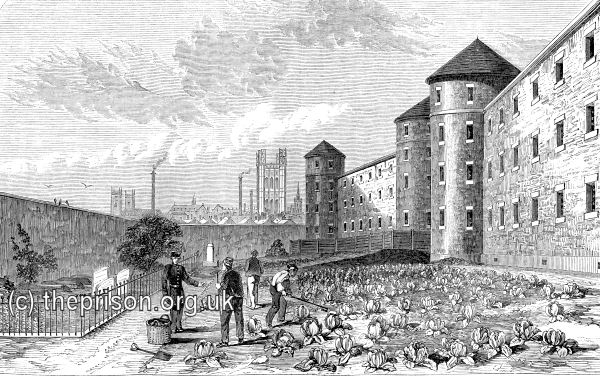

Millbank Penitentiary, London — convicts working in prison garden. © Peter Higginbotham

New arrivals at the prison were given a haircut, bath, and medical examination. Their own clothes were either sold or, if 'foul or unfit to be preserved', burned. The prison uniform, slightly different for the two classes, was decreed to be made of cheap and coarse materials, and distinctively marked so as to identify escapees. The wearing of a black armband (or ribbon for women) was permitted following the death of a near relation.

The prisoners' daily routine comprised ten sections, each signalled by the ringing of a bell:

| Bell | Time | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5.30 (or daybreak in winter) | Rise, dress, comb hair, visit washroom under supervision of Turnkey. |

| 2 | 6.00 | Begin work |

| 3 | 8.30 | Prisoners appointed Wardsmen/Wardswomen collect porridge or gruel from kitchens for distribution to other inmates. |

| 4 | 9.00 | Eat breakfast. |

| 5 | 9.30 | Resume work. |

| 6 | 12.30 | Wardsmen/Wardswomen collect dinners. |

| 7 | 13.00 | Eat dinner and take air or exercise. |

| 8 | 14.00 | Resume work. |

| 9 | 18.00 (or sunset in winter) | Finish work. |

| 10 | 18.00 (or 19.00 in winter) | Return to cell for night. Gruel or porridge delivered to cell. |

Establishing what was eventually to become normal prison practice, all food for Millbank's inmates was supplied by the institution. The prison's 1817 dietary (below) also includes one of the first instances of porridge making its appearance as the standard prisoner's breakfast fare.

| DAILY, 1lb. of Bread, made of whole Meal; and to serve the day. | ||

| BREAKFAST | 1 pint of hot gruel or porridge. | |

| DINNER | Sundays Tuesdays Thursdays Saturdays |

6oz of clods, stickings, or other coarse pieces of Beef (without bone, and after boiling) with ½ a pint of the Broth made therefrom. 1lb. of sound Potatoes, well boiled. |

| Mondays Wednesdays Fridays | 1 quart of Broth, thickened with Scotch barley, rice, potatoes, or pease, with the addition of cabbages, turnips, or other cheap vegetables. 1lb. of sound Potatoes, well boiled. | |

| SUPPER | 1 pint of hot gruel or porridge. | |

| N.B. The only Liquor allowed to prisoners in health (except broth, gruel or porridge) shall be Water. Prisoners, employed in works of extraordinary labour, or under circumstances which may render it necessary, may be allowed an addition to the quantity of their provisions. | ||

The only variation in the dietary came on Christmas Day the when the meat was roasted (rather than boiled) and an additional 8oz of baked pudding was served.

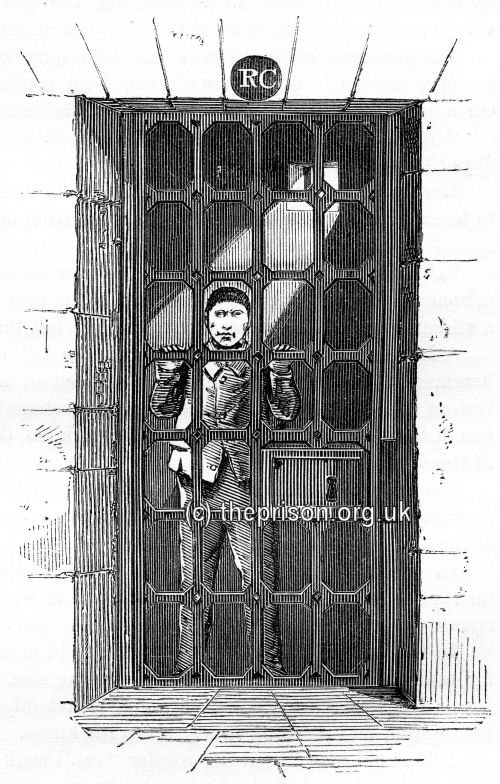

Prisoners who were 'deficient in cleanliness' were liable to have their meat and vegetables withheld. More serious offences could be punished by a diet of bread and water and/or confinement in a dark cell for up to a month.

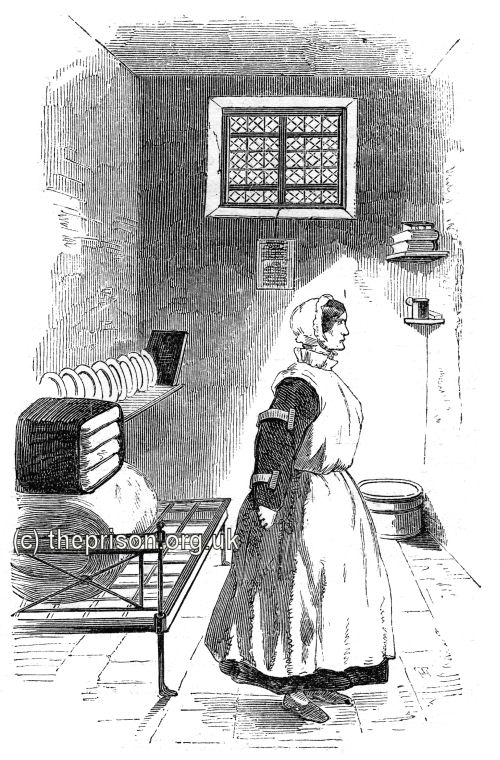

Millbank Penitentiary, London — prisoner in refractory cell. © Peter Higginbotham

Millbank Penitentiary, London — prisoner wearing canvas dress as punishment for tearing her clothes. © Peter Higginbotham

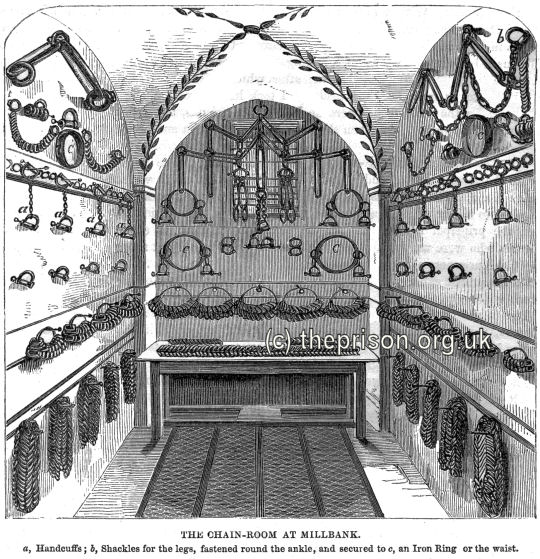

Millbank Penitentiary, London — chains room. © Peter Higginbotham

In 1822, Millbank's Medical Superintendent, Dr Copland Hutchinson, concluded that the Millbank dietary was more liberal than that found in most other prisons. He persuaded the prison's Committee of Management to adopt the new dietary shown below. The most significant change was in the midday dinner provision — the daily pound of potatoes and four-times-a-week ration of meat had gone and in its place was an unchanging portion of ox head soup.

Within a few months, the health of the prisoners was in serious decline. They became pale, languid, thin, and feeble, and unable to perform their usual labour. There were also numerous cases of diarrhoea and dysentery. More than half the inmates were affected, females more than males, and those in the Second Class more than those in the First. One group of prisoners who were almost entirely unscathed were those who worked in the prison kitchens.

Eventually, two outside physicians were called in and diagnosed the mysterious illness as a combination of infectious dysentery and 'sea-scurvy'. Scurvy, whose symptoms included spongy and bleeding gums, results from a vitamin C deficiency but was then attributed to factors such as insufficient food, cold, damp, fatigue, and sea air. An immediate change in the Millbank diet was ordered, with a daily allowance of 4oz of meat and 8oz of rice replacing the dinner-time soup, and white bread being provided instead of brown. Each prisoner was also given an orange at each meal. In the longer term, it was recommended that the amount of meat in the diet should be increased, that only good quality white bread be used, and that at least one meal a day should be given in solid form. The potato ration was not restored, however.

Although the change in the Millbank diet appeared to produce a rapid improvement in the prisoners' health, there was then a widespread relapse. It was decided that the building itself was contributing to the problems and would have to be evacuated while the necessary changes were made. Four naval vessels at Woolwich were pressed into service as prison hulks, the Ethalion and Dromedary housing 467 male convicts and the Narcissus and Heroine 167 females. The transfer of Millbank's residents began in August 1823 and the prison was closed for a year during which time all the rooms were fumigated with chlorine and extensive improvements made to the ventilation and drainage. For the prisoners now on the hulks, conditions were often no less unpleasant than those they had left behind. The continuing level of sickness among the women in particular led to many of them being given free pardons, while some of the men were transferred to the fleet of regular hulks.

Millbank Penitentiary, London — burial ground. © Peter Higginbotham

Despite the efforts to improve the running of Millbank, it continued to suffer from problems and a frequent turnover of governors. More seriously, it became increasingly clear that keeping prisoners separated over long periods was not without its consequences. In 1841, a disturbing increase in the numbers of inmates diagnosed as insane led to the initial period of separation being reduced to the three months. Finally, in 1843, the Home Secretary, Sir James Graham, admitted that as a penitentiary, Millbank had been an entire failure and it would become a short-term holding prison for those awaiting transportation.

From 1849 to 1852, following a cholera outbreak at the prison, part of the establishment was related to Shorncliff Barracks in Kent.

Housing of female convicts at Millbank ended with the opening of Brixton prison, which took on that role.

From 1870, the number of convicts was reduced and part of building was used as a military prison. The remainder housed probationers and those with those of non-Anglican religious beliefs, mainly Roman Catholics.

In 1880, the prison was began receiving 'star class' convicts — those with no previous convictions. In October 1883, while Wormwood Scrubs (then a convict prison) was still under construction, Millbank began to operate as as local prison. Millbank's military prisoners were transferred to Brixton Prison, and male convicts in separate confinement were moved to Wormwood Scrubs. On 1 May 1886, Millbank ceased use as a convict prison and was officially handed over to the local prison authorities.

With the redesignation of Wormwood Scrubs as a local prison in 1890, Millbank was closed and was demolished the following year. The Tate Gallery now occupies the central part of the site.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Holdings include: Register of prisoners (1812-86); Register of male prisoners (1843-74); Register of female prisoners (1843-74); Index to registers of prisoners; Register of deaths and inquests (1848-9).

- Find My Past has digitized many of the National Archives' prison records, including prisoner-of-war records, plus a variety of local records including Manchester, York and Plymouth. More information.

- Prison-related records on

Ancestry UK

include Prison Commission Records, 1770-1951

, and local records from London, Swansea, Gloucesterhire and West Yorkshire. More information.

- The Genealogist also has a number of National Archives' prison records. More information.

Census

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.