Prison Food

Prior to the nineteenth century, much of the gaoler's income came from providing the prison inmates with food, or in charging to allow them to cook their own food in the prison kitchen. In order to maximise profits, the charges set varied according to the prisoner's rank, and where meals were eaten. By 1618, the Fleet's weekly rate, which included wine, ranged from £3 6s 8d for lords, £1 13s 4d for knights, 10s for gentlemen, and 5s for commoners. At other London prisons, the usual rate for board and lodging was 3s per week for gentlemen and 2s for yeomen.

At Newgate, in 1724, those who could afford it dined together in small groups or 'messes', each member taking it in turns to provide the day's requirements such as a joint of mutton, veal, lamb, or beef which was roasted or boiled. A mess of seven persons could, it was said, dine well at a cost of fourpence a head. The food was accompanied by 'Small-Beer very good, for One-penny per Quart Bottle, Strong Drink very good for Three-pence per Winchester Quart [four pints]; Wine Two Shillings per Bottle; Brandy, Six-pence per Quartern [quarter pint] &c.'

Although those who could afford it might prefer to send out for food, rather than eat what the prison kitchen produced, the gaoler sometimes went to some lengths to encourage them otherwise. In 1620, there was a mutiny at the King's Bench prison after the keeper, Sir George Reynell, closed off a window to the street that had previously been used for receiving deliveries of meals from friends or neighbourhood suppliers. The inmates then had to buy their food at inflated prices from the prison kitchen. Sir George's reply was that the closure of the window had been carried out purely for the safe keeping of the prisoners. At the same establishment, another inmate complained that the prison kitchen charged him eightpence for cooking fourpence-worth of fish.

It was not only the price of the food that could lead to complaint, but also its quality. In 1618, insolvent barrister Geffray Mynshul wrote that an unnamed gaoler had sold the prisoners bullock's liver which he had begged for his dog from a butcher's, and had also charged a halfpenny for a quart of water.

Food debtors could sometimes be collected by a 'basket man' who walked the streets calling out 'Bread and meat for the poor prisoners! Contributions were piled into the basket carried on his back and later shared out.

There were also occasional supplies of food from other sources, for example through charitable donations, bequests, or items that had been seized by city officials for contravening some ordinance such as underweight bread or meat being offered for sale on a fish day.

From 1572, convicted felons were also eligible to receive 'county bread' or the 'county allowance' — a small allowance of food or money provided out of county funds. The provision varied widely — from as little as the pennyworth of bread a day supplied at the Monmouth County Gaol, to the two pennyworth of bread and two pennyworth of meat at Northumberland County Gaol. Since the price of wheat varied quiet considerably, the amount of food provided rose and fell in step.

By the early nineteenth century, prisons were beginning to provide food for their inmates. At the new Pentonville Prison, opened in 1842, there was a daily ration of bread, plus a breakfast of cocoa, a dinner of meat, soup and potatoes, and a supper of gruel.

Some prisons gave different allowances to different categories of prisoner. In 1841, at the Exeter Gaol and House of Correction, Dietary No. 1, the most generous, was given to prisoners awaiting trial, to those who were condemned, sentenced to transportation or hard labour, or to females nursing their children. The smaller rations of Dietary No.2 were given to those serving a sentence without hard labour. Dietary No.3, the lowest scale, was reserved for vagrants, and was further reduced for repeat offenders.

In 1864, in an effort to address the wide variations that then existed between different prisons, and different categories of imate, a government report proposed a new set of prison dietaries. A basic dietary of bread and gruel was provided for those not undertaking hard labour, with various additions allowed where labour was imposed. There was then a graded series of dietaries for different lengths of sentence, with prisoners on longer terms eventually being allowed items such as meat and cheese. However, based on advice from various prison authorities, it was now recommended that prisoners sentenced to longer terms of imprisonment should progressively pass through the diets of all the sentences shorter than their own. Women were, as standard, to receive three-quarters of the rations provided to male prisoners. Those serving very short sentences had the plainest food — what might be viewed as a 'short, sharp shock'. The better diet eventually received by serious offenders serving longer term sentences was to ensure that they remained able to perform the labour that was required of them.

Breadmaking at Wormwood Scrubs Prison, 1898. © Peter Higginbotham.

The end of a penal element to prison food came following a review in 1899, when a Departmental Committee recommended that a distinction should no longer be made between hard-labour and non-hard-labour diets. With regard to age and sex, it proposed a new three-way categorisation, namely: males over sixteen, females over sixteen, and juveniles under sixteen of either sex.

Bibliography

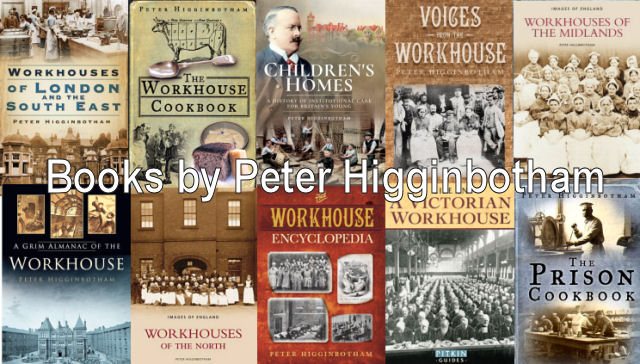

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.