The Cost of Going to Prison

Prior to the nineteeth century, the gaoler or prison keeper was not usually paid a salary for his(or occasionally her) work. However, the position could be quite a lucrative one to hold as the gaoler could obtain a good income from their charges. Anyone going to prison had to pay for their own transport to get their. They then had to pay charges such as an admission fee for a bond to guarantee their good behaviour and regular outgoings during their stay, a fee to the clerk who drew up the bond, and another fee for being entered in the prison register. At the end of their stay, the final charge demanded of all prisoners was a discharge fee. On top of these 'administrative' fees came various other ongoing charges levied by the gaoler. In 1431, for example, Newgate made a charge of fourpence a week towards the running costs of the prison lamps. In 1488, the price for prison-supplied beds at Newgate was set at a penny per week for a bed with sheets, blankets, and a coverlet, and penny per week for a couch. Alternatively, prisoners could bring in their own beds. Some prisons restricted the movement of inmates by the use of leg-irons, which could be dispensed with by making a payment to the gaoler.

On top of the various fees and charges taken by the gaoler, clerk, and so on, additional payments in the form of 'garnish' were exacted from new inmates. At Marshalsea, the garnish comprised a flat payment on arrival by new prisoners of 8s for men or 5s 6d for women, regardless of their standing. Payment of the money allowed access to the common room, use of boiling water from the fire, the cooking of food, and the reading of newspapers. The poet William Fennor, on entering London's Wood Street Compter in 1616, was charged two shillings by the chamberlain for being allocated comfortable accommodation. At dinner-time the next day, a garnish of half a gallon of claret was demanded by his fellow prisoners. A further garnish of 6d for two pints of claret was then extracted by the under-keepers to endow him with the liberty of the prison.

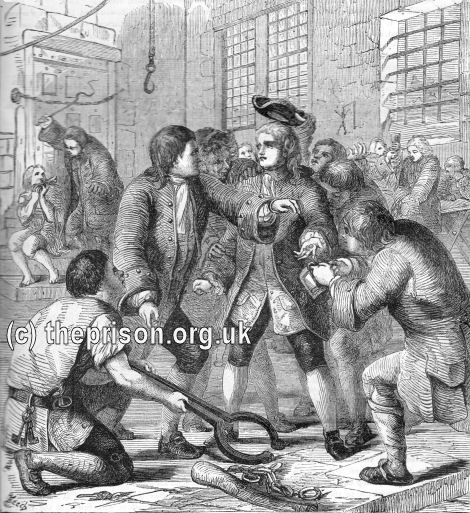

The picture below shows a debtor, newly arrived at the Fleet Prison, being relieved of his hat and other possessions, by the existing inmates.

Debtor arriving at Fleet Prison, London, 1740s. © Peter Higginbotham

The prison keeper was under no obligation to provide food or bedding for those who were not able to furnish it themselves, or to pay the required fees. The totally penniless could end up sleeping on the floor in a dark, damp, rat-infested cellar.

From the 1770s onwards, largely thanks to the efforts of reformers such as John Howard, it became increasingly common for gaolers to be paid a salary and for prisons to provide food and other basic items. Eventually, in 1815, all gaol fees were abolished.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.