Marshalsea Debtors' Prison, Southwark, London

The Marshalsea (whose keeper was known as the Marshal) was erected in around 1329, at the north side of what is now Mermaid Court, off Borough High Street in Southwark. It originally held offenders who were members of the King's household but was later used for the confinement of debtors, pirates, mutineers, and recusants — those refusing to acknowledge the established church. Edmund Bonner, London's last Roman Catholic Bishop, was imprisoned in Marshalsea for the final ten years of his life after refusing to swear the oath of supremacy to Queen Elizabeth I.

In 1729, the report of a government Select Committee on the State of the Gaols found much to criticise at the Marshalsea. John Darby was the prison's assistant marshal, a position he had been granted to hold for life, so long as he did not 'let to farm the said offices, or any of the fees, profits, advantages, or benefits, thereof'. However, the Committee discovered that Darby had

let the profits of the said offices... to William Acton, butcher, the Marshalsea Prison for 140l. per annum; and by the same lease did let the benefit of the lodging of the prisoners, and other advantages, for the further yearly rent of 260l. to be paid to him, clear of all taxes, for the term of 7 years.

That, to make the profits of the Prison arise, to answer the said exorbitant rents, no kind of artifice, or oppression, hath been unpractised.

It appears, upon the examination of many witnesses, that, on the entry of prisoners into the said Prison, money has been extorted from them, for obtaining the liberty of going to the master's side, though the said Darby himself acknowledged, be had no right to any fees, till the prisoner was discharged: And, in order to create a greater profit, by vending liquors, and food, the servants of the keeper have obstructed the bringing in necessary liquors, and provisions, contrary to the express words of the act of parliament, of the 22d and 23d year of King Charles 2d; and have often under the pretence of searching for liquors, treated very rudely and indecently women, who came to relieve and support their husbands, labouring under the hardships and necessities of the gaol: And they raise the price of liquors, and other necessaries, insomuch that the necessitous prisoner is obliged to pay three pence per quart for worse beer, than he can buy out of the Prison for two-pence half-penny; And they have also encouraged a practice, among the prisoners, of forcing those, newly committed, to pay garnish, and of levying fines upon each other, under frivolous pretences; the money, arising from which, as to be spent at the tap-house; so that he, who is tn05t active in exacting it, is favoured, as the greatest friend to the house. This method of levying garnish money, and fines, is so publicly allowed, that there are tables hung up in each room, of the stated garnish fees, some of which amount to 7s. 6d. some to more; and if the unhappy wretch (which is the general case) hath not money to pay them, the prisoners strip him in a riotous manner which, in their cant phrase, they call letting the black dog walk.

This shews the inconveniency of the Keeper's having the advantage of the tap-house; since, to advance the rent thereof, and to consume the liquors, there vended, they not only encourage riot and drunkenness, but also prevent the needy prisoner from being supplied by his friends with the mere necessaries of life, in order to increase an exorbitant gain to their tenants.

And these extortions, though small in the particulars, are very heavy upon the unhappy prisoners, many of whom are so poor, as to be committed for a debt of one shilling only; for, by the usage of the said Court of Record, processes are issued for the smallest sums; and, though the cause of action is but one penny, a process is issued, the process is returned, and the proceedings are carried on, till such time as the costs amount to above 40s. and thereupon the debtor is thrown into prison; and, by adding the costs to the debt, the late act of parliament, against frivolous and vexatious arrests, is eluded: Nor is it probable, that he can be from thence released; for if he was incapable before to pay the cause of action, he must be much more so, when the costs are added thereto; and, if his creditor then relents, he is detained for the gaoler's fees, and costs of suit, infinitely greater than the original debt.

It appeared to the Committee, that there was no list of fees publicly hung up in any part of the Prison, though required by law.

Upon inspection of the several parts of the said gaol, the Committee find, that the said gaol is divided into two divisions, viz. the master's side, and the common side; and that a part thereof is only fenced in with a few weak old boards: That there are several rooms on the master's side kept empty, some with but one or two persons in them, and others at the same time crouded to that degree, as even to make them unhealthy; particularly, in one of the rooms in a part of the Prison, called the Oake, nine men are laid in three beds, and each man pays 2s. 6d. per week; so that room singly produces 1l, 2s. 6d. per week.

It appeared to the Committee that the Gaoler of the said Prison, out of a view of gain, hath frequently refused to remove sick persons, upon complaint of those, who lay in the same bed with them; a particular instance of which follows. Mrs. Mary Trapps was prisoner in the Marshalsea, and was put to lie in the same bed with two other women, each of which paid 2s. 6d. per week chamber rent: She fell ill, and languished for a considerable time; and the last three weeks grew so offensive, that the others were hardly able to bear the room: They frequently complained to the turnkeys, and officers, and desired to be removed; but all in vain: At last she smelt so strong, that the turnkey himself could not bear to come into the room, to hear the complaints of her bedfellows; and they were forced to lie with her, or on the boards, till she died.

And the Committee, inspecting the various parts of the gaol, saw a prisoner, who kept his bed with a fistula, and two other persons obliged to lie with him in the same bed, though each paid 2s. 6d. per week; yet they even submitted to such rent, and usage, rather than be turned down to the common side.

The common side is enclosed with a strong brick wall; In it are now confined upwards of 330 prisoners, most of them in the utmost necessity: They are divided into particular rooms, called wards; and the prisoners, belonging to each ward, are locked up in their respective wards every night; most of which are excessively crowded, thirty, forty, nay fifty, persons having been locked up in some of them, not sixteen foot square; and at the same time that these rooms have been so crowded, to the great endangering the healths of the prisoners, the largest room in the common side hath been kept empty, and the room over George's ward was let out to a taylor, to work in, and no body allowed to lie in it, though all the last year there were sometimes forty, and never less than thirty two, persons locked up in George's ward every night, which is a room of sixteen by fourteen feet, and about eight feet high: The surface of the room is not sufficient to contain that number, when laid down; so that one half are hung up in hammocks, whilst the others lie on the floor under them: The air is so wasted by the number of persons, who breathe in that narrow compass, that it is not sufficient to keep them from stifling, several having in the heat of summer perished for want of air: Every night, at eight of the clock in the winter, and nine in the summer, the prisoners are locked up in their respective wards, and from those hours, until eight of the clock in the morning in the winter, and five in the summer, they cannot, upon any occasion, come out; so that they are forced to ease nature within the room, the stench of which is noisome beyond expression, and it seems surprizing, that it hath not caused a contagion.

The crowding of prisoners together in this manner is one great occasion of the gaol distemper; and, though the unhappy men should escape infection, or overcome it, yet, if they have not relief from their friends, famine destroys them; all the support, such poor wretches have to subsist on, is an accidental allowance of pease, given once a week by a gentleman, who conceals his name, and about thirty pounds of beef, provided by the voluntary contribution of the judge and officers of the Marshalsea, on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday; which is divided into very small portions, of about an ounce and an half, distributed with one fourth part of an half-penny loaf: each of the sick is first served with one of those portions, and those, that remain, are divided amongst the wards; but the numbers of the people in them are so great, that it comes to the turn of each man but about once in fourteen days, and of each woman (they being fewer) once in a week.

When the miserable wretch hath worn out the charity of his friends, and consumed the money, which he hath raised upon his cloaths, and bedding, and hath eat his last allowance of provisions, he usually in a few days grows weak, for want of food, with the symptoms of a hectic fever; and, when he is no longer able to stand, if he can raise 3d. to pay the fee of the common nurse of the prison, he obtains the liberty of being carried into the sick ward, and lingers on for about a month or two, by the assistance of the above-mentioned prison portion of provision, and then dies.

The Committee saw in the Women's Sick Ward, many miserable objects lying, without beds, on the floor, perishing with extreme want; and in the Mens Sick Ward yet much worse: for along the side of the walls of that ward boards were laid upon trestles, like a dresser in a kitchen; and under them, between those trestles, were laid on the floor one tire of sick men, and upon the dresser another tire, and over them hung a third tire in hammocks.

On the giving food to these poor wretches (though it was done with the utmost caution, they being only allowed at first the smallest quantities, and that of liquid nourishment) one died: the vessels of his stomach were so disordered, and contracted, for want of use, that they were totally incapable of performing their office, and the unhappy creature perished about the time of digestion. Upon his body a coroner's inquest sat (a thing which though required by law to be always done, hath for many years been scandalously omitted in this gaol) and the jury found, that he died of want.

Those, who were not so far gone, on proper nourishment given then, recovered, so that not above nine have died since the 25th of March last, the day the Committee first met there, though, before, a day seldom passed without a death, and upon the advancing of the spring, not less than eight or ten usually died every 24 hours. The great numbers, who appeared to have perished for want. induced the Committee to enquire, what charities were given for the subsistence of the prisoners in this gaol: they have as yet been only able to come at full proof of 10l. per annum, left by Sir Thomas Gresham, and one pound per annum, paid by each county in England, commonly called exhibition money; but have reason to believe, there many other sums, which the shortness of the time prevented the Committee from being able fully to discover.

The Marshalsea site is shown on the 1746 map below.

Marshalsea Debtors' Prison site, Southwark, c.1746.

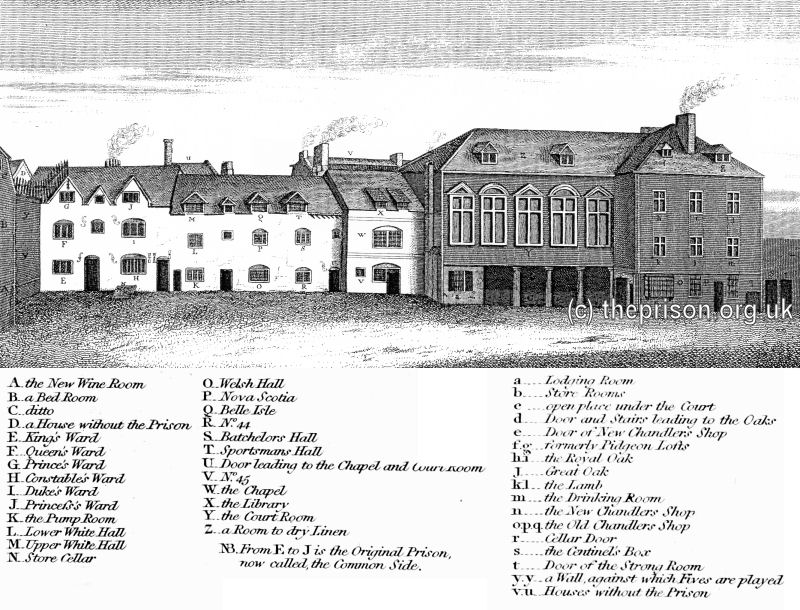

Marshalsea Debtors' Prison, Southwark, London, c.1812. © Peter Higginbotham

In 1784, John Howard wrote:

To this prison of the Court of the Marshalsea, and of the King's Palace-Court of Westminster, are brought debtors affected for the lowest sums, any where within; twelve miles of the palace, except in the city of London; and alto persons committed for piracy.

The deputy marshal, under whose particular custody this prison is, has his appointment from the knight marshal of the king's household for the time being. The great abuses practised by this officer were reported to parliament by the Gaol Committee in 1729.

This prison is held under several leases by the widow of the late deputy marshal at the yearly rent of 101l. It is an old irregular building (rather several buildings) in a spacious court. There are, in the whole, near sixty rooms; and yet only six of them left for common-side debtors. Of the other rooms, — five were let to a man who was not a prisoner: in one of them he kept a chandler's shop; in two he lived with his family: the other two he let to prisoners. Four rooms, the Oaks, were for women. They were too few for the number; and the more modest women complained of the bad company, in which they were confined. There were above forty rooms for men on the master's-side, in which were about sixty beds; yet at my first visits, many prisoners had no beds nor any place to sleep in, but the chapel, and the tap-room. The chamber-rent wants regulation; for in several rooms where four lie in two beds, and in some dark rooms where two lie in one bed, each pays 3s. 6d. a week for his lodging.

The prison is greatly out of repair. No infirmary. The court is well supplied with water. In it the prisoners play at rackets, &c. and in a little back court, the Park, at skittles.

The tap was let to a prisoner in the rules of the King's Bench prison; this prison being just within those rules. I was credibly informed, that one Sunday in the summer 1775, about 600 pots of beer were brought in from a public house in the neighbourhood (Ashmore's) the prisoners not then liking the tapster's beer.

In March 1775, when the number of prisoners was 175, there were with them in this incommodious prison wives and children 46.

Since the act of the 19th of Geo. III. Chap. LXX. there are not so many debtors in this prison as formerly; yet they are increasing, for I find here, and in other prisons, many debtors whose original debts are much under £10. but for the purpose of imprisoning such debtors, they are prosecuted either in the court of exchequer, or in other inferior courts, until the expences of such prosecutions which added to the original debt amount to £10. A fresh action is then taken out in the superior courts, for the small original debt, and the accumulated costs of prosecution.—Thus the salutary purposes of the said act are defeated.

Mr. Henry Allnott, who was many years since a prisoner here, had, during his confinement, a large estate bequeathed to him. He learned sympathy by his sufferings; and left £100 a year for discharging poor debtors from hence, whose debts do not exceed £4. As he bound his manor of Goring in Oxfordshire for charitable uses, this is called the Oxford charity. Many are cleared by it every year.

In 1811, the Marshalsea was rebuilt a little way to the south of its original location, at the south side of Angel Place, and close to the site of the former White Lion prison.

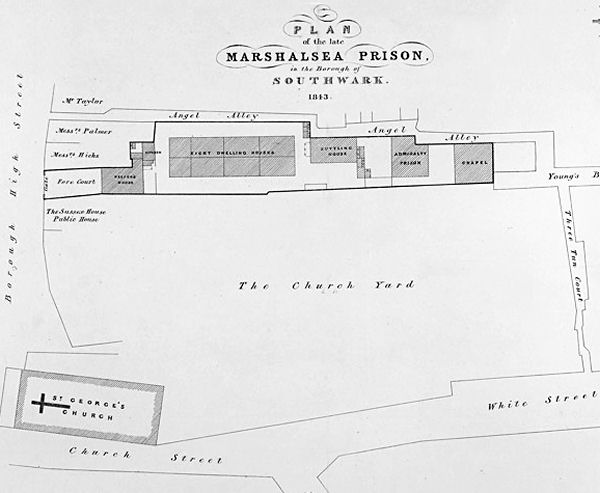

The Marshalsea site is shown on the 1827 map below.

Marshalsea Debtors' Prison site, Southwark, 1827.

Marshalsea Debtors' Prison, Southwark, London, c.1843.m

The new premises were described in 1812 by James Neild:

The new Marshalsea Prison is situate in High-street, in the Borough of Southwark, near St. George's Church, and was formerly the Gaol for the County of Surrey. The entrance-gate fronts the street, and a small area leads to the Keeper's house. Behind it is a brick building, the ground-floor of which contains fourteen rooms in a double row, and the three upper-stories the same number; making in the whole 56 rooms, about 10½ feet square, and 8½ feet high, with boarded floors, a glazed window and fire-place in each, intended for Male Debtors. Nearly adjoining to this is a detached building called the Tap, which has, on the ground-floor, a Beer Room, and another called the Wine Room, for prisoners' and their friends' occasional resort.

The first floor is intended for the Tapster, and one Turnkey, from whose room the window looks into the court-yard of the Admiralty Prisoners. The upper-story has three rooms for Female Debtors, similar to those for the men.

Between this building and the Admiralty Prison there are two solitary cells, 9 feet by 6 feet 6, and 7 feet high, for refractory Debtors; and the iron gratings in the doors look into a small court-yard.

Admiralty Prisoners are here separated from the Debtors: they have a court-yard, 28 feet by 23, with sewers conveniently placed; and two large rooms are to be made into sleeping-cells. Here is a very good bath, with a large copper for warm-water. At the extremity of this long range of building is a neat Chapel, with pews and forms for Debtors, separate from the Admiralty Prisoners.

The Prison is well supplied with water, but the Debtors' court-yard is too small for the numbers generally confined here; the whole area being only 177 feet by 56, and the centre of it occupied by the Debtors' Prison and the Tap, so as to leave no more than a narrow slip on each side, for air and exercise. It is in contemplation, however, to make an addition to it, by the purchase of some land adjoining.

In 1824, the father of twelve-year-old Charles Dickens was imprisoned in the Marshalsea, owing £40 and 10 shillings to a baker. The prison later featured in Charles Dickens' Little Dorrit, serialised in 1855-7:

In 1842, the Marshalsea was closed and its inmates were transferred to the Queen's Prison, as also happened with the Fleet Prison.

The site and buildings, which then comprised the Keeper's house, a substantial three-storey brick building and eight separate dwelling houses of brick and slate, the suttling house, the Admiralty Prison, a chapel and some paved yards, were sold for £5,100 to W.G. Hicks, ironmonger. Parts of some of these were subsequently incorporated into the premises of a hardware merchants at the rear of 207 Borough High Street.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Holdings include: Entry book of Admiralty prisoners (1773-1842); Daybooks of Commitments and discharges (1811-1842).

- Find My Past has digitized many of the National Archives' prison records, including prisoner-of-war records, plus a variety of local records including Manchester, York and Plymouth. More information.

- Prison-related records on

Ancestry UK

include Prison Commission Records, 1770-1951

, and local records from London, Swansea, Gloucesterhire and West Yorkshire. More information.

- The Genealogist also has a number of National Archives' prison records. More information.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.