Pentonville Prison, Islington, London

The idea for the construction of what became Pentonville prison came from the Reverend Whitworth Russell (a former chaplain at Millbank) and William Crawford, who were two of the inspectors appointed by the Inspectors of Prisons, a body established by the 1835 Prison Act to visit and report on the state of the country's local prisons. The two were staunch supporters of the 'separate' system of accommodation, in which inmates ate, worked and slept in their cells, only leaving for activities for exercise and chapel services. The alternative 'silent' system allowed inmates to perform communal labour but not to speak to one another while working. Accordingly, in Russell and Crawford's scheme, inmates would sleep, work and eat in a spacious and self-contained cell, with no contact allowed with other prisoners. The daily routine would include time for reflection, religious devotions, exercise, receive regular visits from prison officers, particularly the chaplain.

Crawford and Russell produced a number of designs for model prisons in which their scheme could be implemented, with some of their plans being taken up by local prisons interested in introducing the separate system. This trend was given added impetus in the 1839 Prisons Act under which all new prison plans required approval from central government in the shape of Joshua Jebb, the Home Office's advisor and subsequently Surveyor General of Prisons. The Act effectively gave official endorsement to the separate system which, it insisted, was quite different from solitary confinement. Crawford and Russell's greatest success, however, came in 1838 when their proposal to erect a large model prison in London gained support from the Home Secretary, Lord Russell, who also just happened to be Whitworth Russell's uncle.

The site chosen for the new 'Model Prison, on the separate system' was at Pentonville in north London. Construction began in April 1840, and the first inmates arrived in December 1842.

In addition to its role as a model prison, Pentonville's function within the penal system was to provide an initial term, normally eighteen months, of probationary discipline and labour for selected convicts prior to their transportation to Van Dieman's Land. Those behaving well would receive a ticket-of-leave, effectively freedom in their new country. Those performing indifferently would be given a probationary pass, a status which imposed some restrictions of their movement and earnings. For those whose conduct at Pentonville was deemed unsatisfactory, their destination would be a convict labour settlement.

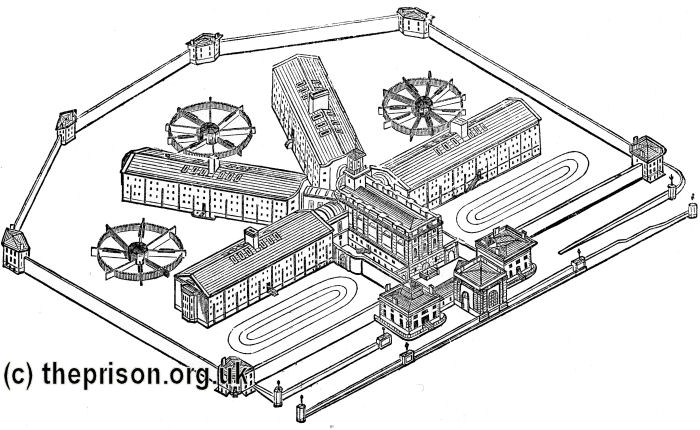

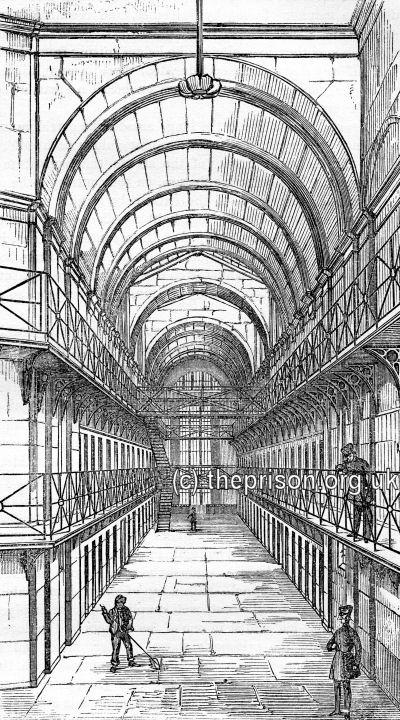

The architect of Pentonville was Joshua Jebb, but its design was clearly based on the ideas of Crawford and Russell. The main prison building comprised a central administration block from which four wings radiated like the spokes of a half-cartwheel. Each wing contained 130 cells arranged in three galleries, one above the other, with each floor containing forty or so individual cells. From the central hall it was possible for staff to have a view of every cell door. Every cell was fitted with an alarm handle which rang a bell and raised a semaphore indicator outside the cell's sound-proof door.

Pentonville Prison — bird's-eye view, London, 1850s. © Peter Higginbotham

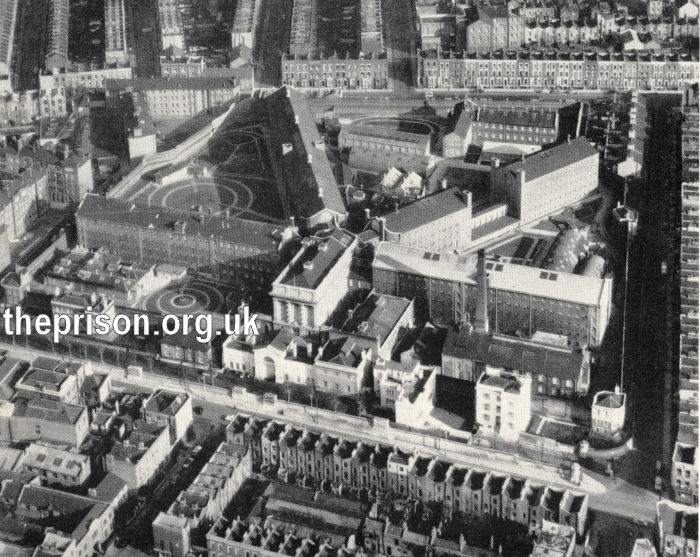

Pentonville Prison — bird's-eye view, London. © Peter Higginbotham

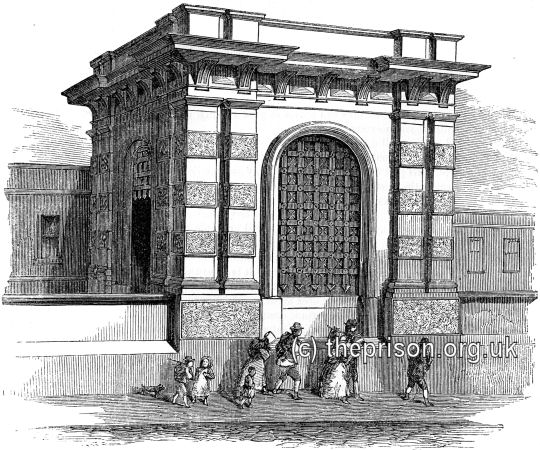

Pentonville Prison — main gate, London, 1850s. © Peter Higginbotham

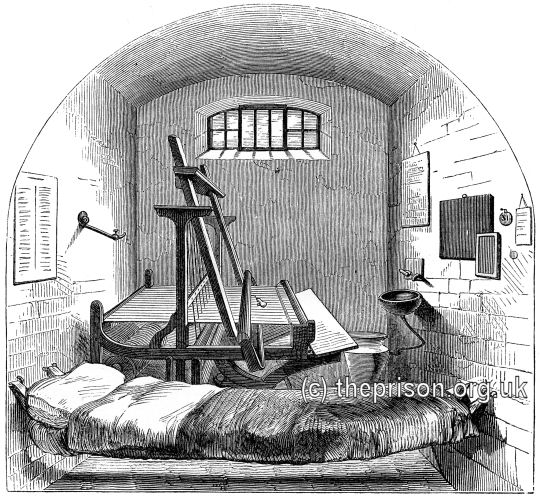

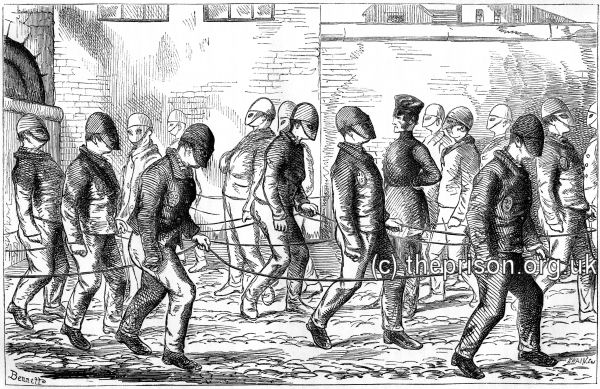

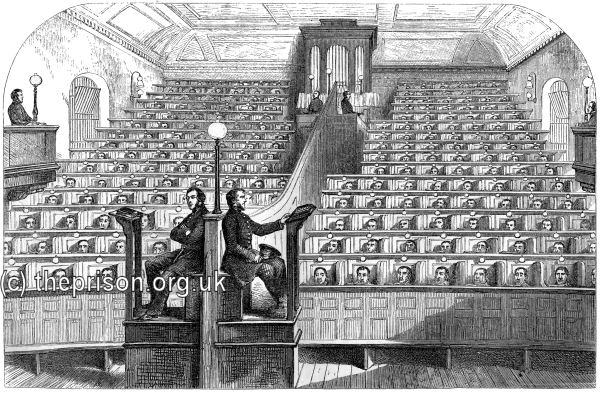

The regime imposed at Pentonville was a rigorous form of the separate system. Prisoners slept, worked and ate in their cells, only going outside for exercise or to attend chapel, at which times they wore turned-down caps (later masks) to conceal their faces. The circular exercise yards were divided into individual segments at the centre of which was an observation post. The chapel, too, was constructed with partitions between each seat to prevent communication.

An important aim of Pentonville was to equip each inmate with a trade by which they could earn their living in Australia. Instructors were employed for a variety of trades including carpentry, shoemaking, tailoring, rug and mat weaving, linen and cotton weaving, and basket making. Prisoners were also provided with twice-weekly classes which included reading, writing, arithmetic, history, geography, grammar, and scripture. A bible, prayer-book and hymn-book were given to every inmate able to use them.

Pentonville Prison — cell, London, 1850s. © Peter Higginbotham

Pentonville Prison — corridor with open galleries, London, 1850s. © Peter Higginbotham

While moving around the prison, inmates were required to space themselves apart while holding onto a long chain. Their masks prevented communication or recognition of one another.

Pentonville Prison — masked prisoners, London, 1850s. © Peter Higginbotham

Pentonville Prison — partitioned chapel seats, London, 1850s. © Peter Higginbotham

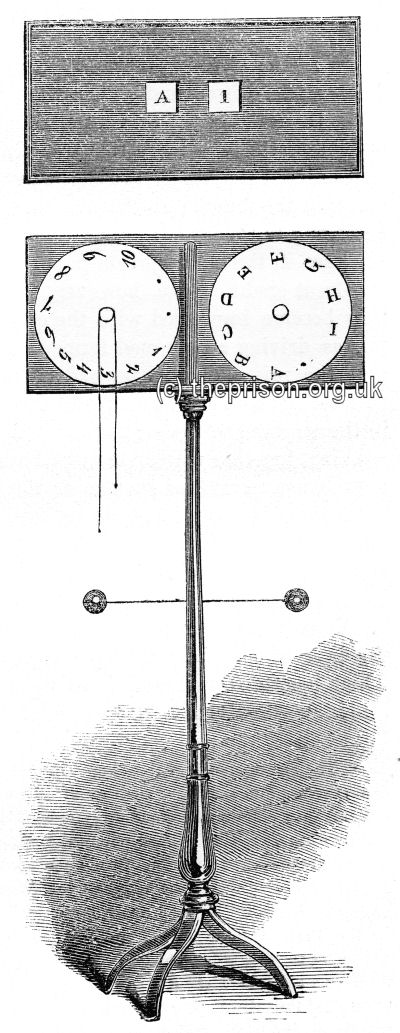

The chapel was equipped with a device for silently signalling to the prisoners the order of their leaving the building.

Pentonville Prison — chapel leaving signal, London, 1850s. © Peter Higginbotham

As at Millbank, the daily routine, from rising at 05.30 till lights out at 21.00, was timetabled with military precision. Parties of sixteen prisoners, in single file at five-yard intervals, were marched from their cells for sessions of exercise, worship, or labour — pumping water from the prison's own 370-foot deep artesian well. The warders' activities were regulated by special clocks around the prison, with levers requiring to be pressed at preset times. Moving inmates from their cells to the chapel, for example, was to occupy exactly six and a half minutes.

The Pentonville inmates' dietary is shown below:

Dinner. 4oz of cooked meat, weighed when cooked, without bone, and ½ pint of soup, and 1lb. potatoes, weighed when boiled.

Supper. 1 pint of gruel, sweetened with 6 drams molasses.

Bread, 20oz per diem. A liberal allowance of salt.

Soup made with liquor of meat of the same day, strengthened by 3 ox-heads to 100 pints. Barley, peppers, and carrots added, and a seasoning of onions. Gruel, 1½oz oatmeal to 1 pint.

In November 1843, The Times reported that after barely six months at Pentonville, two inmates had been 'driven mad by the severity and the seclusion of its discipline', requiring their removal to the Bethlehem Hospital. It condemned the prison's 'maniac-making system' which, it noted, subjected prisoners to solitude for a period six times as long as that which the Millbank authorities had now agreed was the safe maximum for such confinement. For the first few years of its life, the level of such problems was insufficient to cause the authorities serious concern. However, in 1848, the Pentonville Commissioners noted 'the great number of cases of death and of insanity, as compared with that of former years'.

Ironically, it was not only the convicts who appeared to suffer ill effects from the new prison buildings. In 1847, Whitworth Russell committed suicide at Millbank. William Crawford died in the same year after collapsing during a meeting at Pentonville.

Despite the problems experienced at Pentonville, it marked the start of a boom in prison construction. In the six years following its building, fifty-four new prisons were constructed, providing 11,000 separate cells. Pentonville's open gallery radial design became a model for many new local prison buildings and between 1842 and 1877, around twenty gaols or houses of correction were erected on similar lines.

In the 1860s, Pentonville was used to house military prisoners, who contributed labour for enlarging the buildings.

In 1885, the prison ceased operating as a convict prison and was taken over for use as a local prison. After Newgate prison closed in 1902, condemned prisoners were taken to Pentonville to be executed. The prison also provided training for those wanting to pursue a career as an executioner. The last hanging at the prison, in July 1961 was of Edwin Bush, convicted for the murder of a shop assistant.

The prison continues in operation until the present day.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Holdings include: Prison registers (1842-85); index to registers of prisoners (1866-74, 1877-85); Photograph albums of prisoners (1876-85); Visitors' order books (1849-50); Minute books (1842-50).

- Find My Past has digitized many of the National Archives' prison records, including prisoner-of-war records, plus a variety of local records including Manchester, York and Plymouth. More information.

- Prison-related records on

Ancestry UK

include Prison Commission Records, 1770-1951

, and local records from London, Swansea, Gloucesterhire and West Yorkshire. More information.

- The Genealogist also has a number of National Archives' prison records. More information.

Census

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.