Prisoner of War Camp, Norman Cross, Huntingdonshire

In 1914, Francis Abell wrote:

In the year 1796 it became absolutely necessary that special accommodation should be provided for the ever-increasing number of prisoners of war brought to Britain. The hulks were full to congestion, the other regular prisons,—such as they were,—the improvised prisons, and the hired houses, were crowded; disease was rife among the captives on account of the impossibility of maintaining proper sanitation, and the spirit of revolt was showing itself among men just then in the full flush of the influences of the French Revolution. Norman Cross was selected as the site of a prison which should hold 7,000 men, and it was well chosen, being a tract of land forty acres in extent, healthily situated on high ground, connected with the sea by water-ways via Lynn and Peterborough; and with London, seventy-eight miles distant, by the Great North Road. Time pressed; buildings of stone or brick were not to be thought of, so it was planned that all should be of wood, surrounded by a brick wall, but this last was not completed for some time after the opening of the prison. The skeletons of the prison blocks were framed and shaped in London, sent down, and in four months, that is to say in March 1797, the labour of 500 carpenters, working Sundays and week-days, rendered some of the blocks ready for habitation.

The first agent appointed was Mr. Delafons, but he only acted for a few days previous to the arrival of Mr. James Perrot from Portchester, on April 1, 1797. The superintendent of the transport of the prisoners was Captain Daniel Woodriff, R.N. On March 23, 1797, Woodriff received notice and instructions about the first arrival of prisoners. On March 26 they came —934 in number—in barges from Lynn to Yaxley, at the rate of 1s. 10d. per man, and victualling at 7d. per man per day, the sustenance being one pound of bread or biscuit, and three quarters of a pound of beef.

The arrivals came in fast, so that between April 7 and May 18, 1797, 3,383 prisoners (exclusive of seven dead and three who escaped), passed under the care of the ten turnkeys and the eighty men of the Caithness Legion who guarded Norman Cross.

Complaints and troubles soon came to light. A prisoner in 1797, 'who appeared above the common class of men'. complained that the bread and beef were so bad that they were not fit for a prisoner's dog to eat, that the British Government was not acquainted with the treatment of the prisoners, and that this was the agent's fault for not keeping a sufficiently strict eye upon his subordinates. This was confirmed, not only by inquiry among the prisoners, but by the who said 'as fellow creatures they must allow that the provisions given to the prisoners were not fit for them to eat, and that the water they had was much better than the beer'. In spite of this evidence, the samples sent up by the request of the 'Sick and Hurt' Office in reply to this complaint, were pronounced good.

In July 1797 the civil officials at Norman Cross complained of annoyances, interferences, and insults from the military. Major-General Bowyer, in command, in his reply stated: 'I cannot conceive the civil officers have a right to take prisoners out of their prisons to the canteens and other places, which this day has been mentioned to me.'

By July 18 such parts of the prison as were completed were very full, and in November the buildings were finished, and the sixteen blocks, each holding 400 prisoners, were crowded. The packing of the hammocks in these blocks was close, but not closer than in the men-of-war of the period, and not very much closer than in the machinery-crowded big ships of to-day. The blocks, or casernes as they were called, measured 100 feet long by twenty-four feet broad, and were two stories high. On the ground floor the hammocks were slung from posts three abreast, and there were three tiers. In the upper story were only two tiers. As to the life at Norman Cross, it appears to me from the documentary evidence available to have been more tolerable than at any of the other great prisons, if only from the fact that the place had been specially built for its purpose, and was not, as in most other places, adapted. The food allowance was the same as elsewhere; viz., on five days of the week each prisoner had one and a half pounds of bread, half a pound of beef, greens or pease or oatmeal, and salt. On Wednesday and Friday one pound of herrings or codfish was substituted for the beef, and beer could be bought at the canteen. The description by George Borrow in Lavengro—'rations of carrion meat and bread from which I have seen the very hounds occasionally turn away', is now generally admitted to be as inaccurate as his other remarks concerning the Norman Cross which he could only remember as a very small boy.

The outfit was the same as in other prisons, but I note that in the year 1797 the store-keeper at Norman Cross was instructed to supply each prisoner as often as was necessary, with one jacket, one pair of trousers, two pairs of stockings, two shirts, one pair of shoes, one cap, and one hammock. By the way, the prisoners' shoes are ordered 'not to have long straps for buckles, but short ears for strings'.

On August 8, 1798, Perrot writes from Stilton to Woodriff:

'If you remember, on returning from the barracks on Sunday, Captain Llewellin informed us that a report had been propagated that seven prisoners intended to escape that day, which we both looked upon as a mere report; they were counted both that night, but with little effect from the additions made to their numbers by the men you brought from Lynn, and yesterday morning and afternoon, but in such confusion from the prisoners refusing to answer, from others giving in fictitious names, and others answering for two or three. In consequence of all these irregularities I made all my clerks, a turnkey, and a file of soldiers, go into the south east quadrangle this morning at five o'clock, and muster each prison separately, and found that six prisoners from the Officers' Prison have escaped, but can obtain none of their names except Captain Dorfe, who some time ago applied to me for to obtain liberty for him to reside with his family at Ipswich where he had married an English wife. The officers remaining have separately and conjunctively refused to give the names of the other five, for which I have ordered the whole to be put on half allowance to-morrow. After the most diligent search we could only find one probable place where they had escaped, by the end next the South Gate, by breaking one of the rails of the picket, but how they passed afterwards is a mystery still unravelled.'

During the years 1797-8 there were many Dutch prisoners here, chiefly taken at Camperdown.

William Prickard, of the Leicester Militia, was condemned to receive 500 lashes for talking of escape with a prisoner.

On February 21, 1798, Mr. James Stewart of Peterborough thus wrote to Captain Woodriff:

'I have received a heavy complaint from the prisoners of war of being beat and otherwise ill-treated by the officials at the Prison. I can have no doubt but that they exaggerate these complaints, for what they describe as a dungeon I have140 PRISONERS OF WAR IN BRITAIN examined myself and find it to be a proper place to confine unruly prisoners in, being above ground, and appears perfectly dry. How far you are authorized to chastise the prisoners of war I cannot take upon me to determine, but I presume to think it should be done sparingly and with temper. I was in hopes the new system adopted, with the additional allowance of provisions would have made the prisoners more easy and contented under their confinement, but it would appear it caused more turbulence and uneasiness... That liquor is conveyed to the prisoners I have no doubt, you know some of the turnkeys have been suspected.'

Two turnkeys were shortly afterwards dismissed for having conveyed large quantities of ale into the prison.

Rendered necessary by complaints from the neighbourhood, the following order was issued by the London authorities in 1798.

'Obscene figures and indecent toys and all such indecent representations tending to disseminate Lewdness and Immorality exposed for sale or prepared for that purpose are to be instantly destroyed.'

Constant escapes made the separation of officers from men and the suspension of all intercourse between them to be strictly enforced.

Perrot died towards the end of 1798, and Woodriff was made agent in January 1799. Soon after Woodriff's assuming office the Mayor of Lynn complained of the number of prisoners at large in the town, and unguarded, waiting with Norman Cross passports for cartel ships to take them to France. To appreciate this complaint we must remember that the rank and file, and not a few of the officers, of the French Revolutionary Army and Navy, who were prisoners of war in Britain, were of the lowest classes of society, desperate, lawless, religionless, unprincipled men who in confinement were a constant source of anxiety and watchfulness, and at large were positively dangers to society. If a body of men like this got loose, as did fifteen on the night of April 5, 1799, from Norman Cross, the fact was enough to carry terror throughout a countryside.

Yet there was a request made this year from the Norman Cross prisoners that they might have priests sent to them. At first the order was that none should be admitted except to men dangerously ill, but later, Ruello and Vexier were permitted to reside in Number 8 Caserne, under the rule 'that your officers do strictly watch over their communication and conduct, lest, under pretence of religion, any stratagems or devices be carried out to the public prejudice by people of whose disposition to abuse indulgence there have already existed but too many examples'.

That Captain Woodriff's position was rendered one of grave anxiety and responsibility by the bad character of many of the prisoners under his charge is very clear from the continual tenor of the correspondence between him and the Transport Board. The old punishment of simple confinement in the Black Hole being apparently quite useless, it was ordered that offenders sentenced to the Black Hole should be put on half rations, and also lose their turn of exchange. This last was the punishment most dreaded by the majority of the prisoners, although there was a regular market for these turns of exchange, varying from £40 upwards, which would seem to show that to many a poor fellow, life at Norman Cross with some capital to gamble with was preferable to a return to France in exchange for a British prisoner of similar grade, only to be pressed on board a man-of-war of the period, or to become a unit of the hundreds and thousands of soldiers sent here and there to be maimed or slaughtered in a cause of which they knew little and cared less.

The year 1799 seems to have been a disturbed one at Norman Cross. In August the prisoners showed their resentment at having detailed personal descriptions of them taken, by disorderly meetings, the result being that all trafficking between them was stopped, and the daily market at the prison-gate suspended.

Stockdale, the Lynn manager of the prison traffic between. the coast and Norman Cross, writes on one occasion that of 125 prisoners who had been started for the prison, 'there were two made their escape, and one shot on their march to Lynn, and I am afraid we lost two or three last night... there are some very artful men among them who will make their escape if possible'.

Attempts to escape during the last stages of the journey from the coast to the prison were frequent. On February 4, 1808, the crews of two privateers, under an escort of the 77th Regiment, were lodged for the night in the stable of the Angel Inn at Peterborough. One Simon tried to escape. The sentry challenged and fired. Simon was killed, and the coroner's jury brought in the verdict of 'Justifiable homicide'.

On another occasion a column of prisoners was crossing the Nene Bridge at Peterborough, when one of them broke from the ranks, and sprang into the river. He was shot as he rose to the surface.

On account of the proximity of Norman Cross to a countryside of which one of the staple industries was the straw manufacture, the prevention of the smuggling of straw into the prison for the purpose of being made into bonnets, baskets, plaits, &c., constantly occupied the attention of the authorities. In 1799 the following circular was sent by the Transport Board to all prisons and depots in the kingdom:

'Being informed that the Revenues and Manufactures of this country are considerably injured by the extensive sale of Straw Hats made by the Prisoners of" War in this country, we do hereby require and direct you to permit no Hat, Cap, or Bonnet manufactured by any of the Prisoners of War in your custody, to be sold or sent out of the Prison in future, under any pretence whatever, and to seize and destroy all such articles as may be detected in violation of this order.'

This traffic, however, was continued, for in 1807 the Transport Board, in reply to a complaint by a Mr. John Poynder to Lord Liverpool, 'requests the magistrates to help in stopping the traffic with prisoners of war in prohibited articles, straw hats and straw plait especially, as it has been the means of selling obscene toys, pictures, &c., to the great injury of the morals of the rising generation '

To continue the prison record in order of dates: in 1801 the Transport Board wrote to Otto, Commissioner in England of the French Republic,

'Sir:

'Having directed Capt. Woodriff, Superintendant at Norman Cross Prison, to report to us on the subject of some complaints made by the prisoners at that place, he has informed me of a most pernicious habit among the prisoners which he has used every possible means to prevent, but without success. Some of the men, whom he states to have been long confined without receiving any supplies from their friends, have only the prison allowance to subsist on, and this allowance he considers sufficient to nourish and keep in health if they received it daily, but he states this is not the case, although the full ration is regularly issued by the Steward to each mess of 12 men. There are in these prisons, he observes, some men—if they deserve that name—who possess money with which they purchase of some unfortunate and unthinking fellow-prisoner his ration of bread for several days together, and frequently both bread and beef for a month, which he, the merchant, seizes upon daily and sells it out again to some other unfortunate being on the same usurious terms, allowing the former one half-penny worth of potatoes daily to keep him alive. Not contented with this more than savage barbarity, he purchases next his clothes and bedding, and sees the miserable man lie naked on his plank unless he will consent to allow him one half-penny a night to lie in his own hammock, which he makes him pay by a further deprivation of his ration when his original debt is paid.... In consequence of this representation we have directed Capt. Woodriff to keep a list of every man of this description of merchants above mentioned in order they may be put at the bottom of the list of exchange.'

In this year a terrible epidemic carried off nearly 1,000 prisoners. The Transport Board's Surveyor was sent down, and he reported that the general condition of the prison was very bad, especially as regarded sanitation. The buildings were merely of fir-quartering, and weather-boarded on the outside, and without lining inside, the result being that the whole of the timbering was a network of holes bored by the prisoners in order to get light inside. In the twelve solitary cells of the Black Hole there was no convenience whatever. The wells were only in tolerable condition. The ventilation1 of the French officers' rooms was very bad. The hospital was better than other parts of the prison.

It was at about this time that the alarm was widespread that the prisoners of war in Britain were to co-operate with an invasion by their countrymen from without. General Boyer, at Tiverton in 1803, 'whilst attentive to the ladies, did not omit to curse, even to them, his fate in being deprived of his arms, and without hope of being useful to his countrymen when they arrive in England'. Rochambeau at Norman Cross was even more ridiculous, for when he heard that Bonaparte's invasion was actually about to come off, he appeared for two days in the airing ground in full uniform, booted and spurred. Later news sent him into retirement.

At this time escapes seem to have been very frequent, and this in spite of the frequent changing of the garrison, and the rule that no soldier knowing French should be on guard duty. All implements and edged tools were taken from the prisoners, only one knife being allowed, which was to be returned every night, locked up in a box, and placed in the Guard-room until the next morning, and failure to give up knives meant the Black Hole. Any prisoner attempting to escape was to be executed immediately, but I find no record of this drastic sentence being carried into effect.

From The Times of October 15, 1804, I take the following:

'An alarming spirit of insubordination was on Wednesday evinced by the French prisoners, about 3,000, at Norman Cross. An incessant uproar was kept up all the morning, and at noon their intention to attempt the destruction of the barrier of the prison became so obvious that the CO. at the Barrack, apprehensive that the force under his command, consisting only of the Shropshire Militia and one battalion of the Army of reserve, would not be sufficient in case of necessity to environ and restrain so large a body of prisoners, dispatched a messenger requiring the assistance of the Volunteer force at Peterborough. Fortunately the Yeomanry had had a field day, and one of the troops was undismissed when the messenger arrived. The troops immediately galloped into the Barracks. In the evening a tumult still continuing among the prisoners, and some of them taking advantage of the extreme darkness to attempt to escape, further reinforcements were sent for and continued on duty all night. The prisoners, having cut down a portion of the wood enclosure during the night, nine of them escaped through the aperture. In another part of the prison, as soon as daylight broke, it was found that they had undermined a distance of 34 feet towards the Great South Road, under the fosse which surrounds the prison, although it is 4 feet deep, and it is not discovered they had any tools. Five of the prisoners have been re-taken.'

A little later in the year, on a dark, stormy Saturday night, seven prisoners escaped through a hole they had cut in the wooden wall, and were away all Sunday. At 8 p.m. on that day, a sergeant and a corporal of the Durham Militia, on their way north on furlough, heard men talking a 'foreign lingo ' near Whitewater toll-bar. Suspecting them to be escaped prisoners, they attacked and secured two of them, but five got off. On Monday two of these were caught near Ryall toll-bar in a state of semi-starvation, having hidden in Uffington Thicket for twenty-four hours; the other three escaped.

In November 1807 a brick wall was built round Norman Cross prison; the outer palisade which it replaced being used to repair the inner.

In 1809 Flaigneau, a prisoner, was tried at Huntingdon for murdering a turnkey. The trial lasted six hours, but in spite of the instructions of the judge, the jury brought him in Not Guilty.

Forgery and murder brought the prisoners under the Civil Law. Thus in 1805 Nicholas Deschamps and Jean Roubillard were tried at Huntingdon Summer Assizes for forging £1 bank notes, which they had done most skilfully. They were sentenced to death, but were respited during His Majesty's pleasure, and remained in Huntingdon gaol for nine years, until they were pardoned and sent back to France in 1814.

From the Stamford Mercury of September 16, 1808, I take the following: 'Early on Friday morning last Charles François Maria Boucher, a French officer, a prisoner of war in this country, was conveyed from the County Gaol at Huntingdon to Yaxley Barracks where he was hanged, agreeable to his sentence at the last assizes, for stabbing with a knife, with intent to kill Alexander Halliday, in order to effect his escape from that prison. The whole garrison was under arms and all the prisoners in the different apartments were made witnesses of the impressive scene.'

By the Treaty of Paris, May 30, 1814, Peace was declared between France and Britain, and in the same month 4,617 French prisoners at Norman Cross were sent home via Peterborough and Lynn unguarded, but the prison was not finally evacuated until August. It was never again used as a prison, but was pulled down and sold.

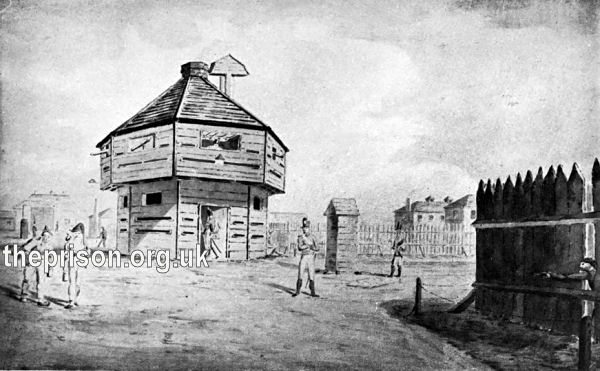

Norman Cross Prisoner of War Camps, Huntingdonshire, c.11803.

The Block House at Norman Cross Prisoner of War Camp, c.1809.

Plait merchants trading with prisoners at Norman Cross Prisoner of War Camp.

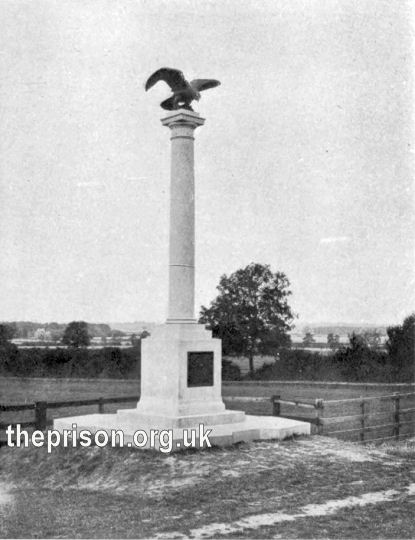

On 28 July 1914, a century after the prison closed, a memorial to the prisoners of war who died at Norman Cross was unveiled by Lord Weardale. It carried the inscription:

In Memoriam. This column was erected A.D. 1914 to the memory of 1,770 soldiers and sailors, natives or allies of France, taken prisoners of war during the Republican and Napoleonic wars with Great Britain, A.D. 1793-1814, who died in the military depot at Norman Cross, which formerly stood near this spot, 1797-1814.

Memorial to French Prisoners who died at Norman Cross, 1914.

.Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Has Registers of Prisoners of War held at Norman Cross.

- FindMyPast has an extensive collection of Prisoner of War records from the National Archives covering both land- and ship-based prisons (1715-1945).

Bibliography

- Abell, Francis Prisoners of War in Britain 1756 to 1815 (1914, OUP)

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.