Mill Prison, Plymouth, Devon

In 1695, an old mill at Mill Bay (or Millbay) was converted for use as a prison, variously known as the Old Mill Prison, Mill Prison, or Millbay Prison.

From the time of the Seven Years War (1756-63) until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, Mill Prison was used to house Prisoners of War, primarily from France, America and Denmark.

In 1914, Francis Abell wrote:

Saxon prisoners taken at Leuthen were at the 'New Prison,' Plymouth, in 1758. In this year they addressed a complaint to the authorities, praying to be sent elsewhere, as they were ostracized, and even reviled, by the French captives, and a round-robin to the officer of the guard, reminding him that humanity should rule his actions rather than a mere delight in exercising authority, and hinting that officers who had made war the trade of their lives probably knew more about its laws than Mr. Tonkin, the Commissioner in charge of them, appeared to know.

In 1760 no less than 150 prisoners contrived to tunnel their way out of the prison, but all except sixteen were recaptured. Of the life at the old Mill Prison, as it was then called, during, the War of American Independence, a detailed account is given by Charles Herbert of Newburyport, Massachusetts, captured in the Dolton, in December 1776, by H.M.S. Reasonable, 64.

With his sufferings during the voyage to England we have nothing to do, except that he was landed at Plymouth so afflicted with 'itch', which developed into small-pox, that he was at once taken to the Royal Hospital. It is pleasing to note that he speaks in the highest terms of the care and kindness of the doctor and nurses of this institution.

When cured he was sent to Mill Prison, and here made money by carving in wood of boxes, spoons and punch ladles, which he sold at the Sunday market.

Very soon the Americans started the system of tunnelling out of the prison, and attempting to escape, which only ceased with their final discharge. Herbert was engaged in the scheme of an eighteen feet long excavation to a field outside, the earth from which, they rammed into their sea-chests. By this, thirty-two men got out, but eleven were captured, he being one. Men who could make no articles for sale in the market sold their clothes and all their belongings.

Theft among the prisoners was punished by the offenders being made to run the gauntlet of their comrades, who were armed with nettles for the occasion.

Herbert complains bitterly of the scarcity and quality of the provisions, particularly of the bread, which he says was full of straw-ends. 'Many are tempted to pick up the grass in the yard and eat it; and some pick up old bones that have been laying in the dirt a week or ten days and pound them to pieces and suck them. Some will pick snails out of holes in the wall and from among the grass and weeds in the yard, boil them, eat them, and drink the broth. Men run after the stumps of cabbages thrown out by the cooks into the yard, and trample over each other in the scuffle to get them.'

Christmas and New Year were, however, duly celebrated, thanks to the generosity of the prison authorities, who provided the materials for two huge plum-puddings, served out white bread instead of the regulation 'Brown George', mutton instead of beef, turnips instead of cabbage, and oatmeal.

Then came a time of plenty. In London £2,276 was subscribed for the prisoners, and £200 in Bristol. Tobacco, soap, blankets, and extra bread for each mess were forthcoming, although the price of tobacco rose to five shillings a pound. Candles were expensive, so marrow-bones were used instead, one bone lasting half as long as a candle.

On February i, 1778, five officers Captains Henry and Eleazar Johnston, Offin Boardman, Samuel Treadwell, and Deal, got off with two sentries who were clothed in mufti, supplied by Henry Johnston. On February 17, the two soldiers were taken, and were sentenced, one to be shot and the other to 700 lashes, which punishment was duly carried out. Of the officers, Treadwell was recaptured, and suffered the usual penalty of forty days Black Hole, and put on half allowance. Continued attempts to escape were made, and as they almost always failed it was suspected that there were traitors in the camp. A black man and boy were discovered: they were whipped, and soon after, in reply to a petition from the whites, all the black prisoners were confined in a separate building, known as the 'itchy yard.'

Still the attempts continued. On one occasion two men who had been told off for the duty of emptying the prison offal tubs into the river, made a run for it. They were captured, and among the pursuers was the prison head-cook, whose wife held the monopoly of selling beer at the prison gate, the result being that she was boycotted.

Much complaint was made of the treatment of the sick, extra necessaries being only procurable by private subscription, and when in June 1778, the chief doctor died, Herbert writes: 'I believe there are not many in the prison who would mourn, as there is no reason to expect that we can get a worse one.'

On Independence Day, July 4, all the Americans provided themselves with crescent-shaped paper cockades, painted with the thirteen stars and thirteen stripes of the Union, and inscribed at the top 'Independence', and at the bottom 'Liberty or Death'. At one o'clock they paraded in thirteen divisions. Each in turn gave three cheers, until at the thirteenth all cheered in unison.

The behaviour of a section of blackguards in the community gave rise to fears that it would lead to the withdrawal of charitable donations. So articles were drawn up forbidding, under severe penalties, gambling, 'blackguarding', and bad language. This produced violent opposition, but gradually the law-abiders won the day.

An ingenious attempt to escape is mentioned by Herbert. Part of the prison was being repaired by workmen from outside. An American saw the coat and tool-basket of one of these men hanging up, so he appropriated them, and quietly sauntered out into the town unchallenged. Later in the day, however, the workman recognized his coat on the American in the streets of Plymouth, and at once had him arrested and brought back.

On December 28, 1778, Herbert was concerned in a great attempt to escape. A hole nine feet deep was dug by the side of the inner wall of the prison, thence for fifteen feet until it came out in a garden on the other side of the road which bounded the outer wall. The difficulty of getting rid of the excavated dirt was great, and, moreover, excavation could only be proceeded with when the guard duty was performed by the Militia regiment, which was on every alternate day, the sentries of the 13th Regular regiment being far too wide awake and up to escape-tricks. Half the American prisoners some two hundred in number had decided to go. All was arranged methodically and without favour, by drawing lots, the operation being conducted by two chief men who did not intend to go.

Herbert went with the first batch. There were four walls, each eight feet high, to be scaled. With five companions Herbert managed these, and got out, their aim being to make for Teignmouth, whence they would take boat for France. Somehow, as they avoided high roads, and struck across fields, they lost their bearings, and after covering, he thinks, at least twenty miles, sat down chilled and exhausted, under a haystack until day-break. They then restarted, and coming on to a high road, learned from a milestone that, after all, they were only three miles from Plymouth!

Day came, and with it the stirring of the country people. To avoid observation, the fugitives quitted the road, and crept away to the shelter of a hedge, to wait, hungry, wet, and exhausted, during nine hours, for darkness. The end soon came.

In rising, Herbert snapped a bone in his leg. As it was being set by a comrade, a party of rustics with a soldier came up, the former armed with clubs and flails. The prisoners were taken to a village, where they had brandy and a halfpenny cake each, and taken back to Plymouth.

At the prison they learned that 109 men had got out, of whom thirty had been recaptured. All had gone well until a boy, having stuck on one of the walls, had called for help, and so had given the alarm. Altogether only twenty-two men escaped. Great misery now existed in the prison, partly because the charitable fund had been exhausted which had hitherto so much alleviated their lot, and partly on account of the number of men put on half allowance as a result of their late escape failure, and so scanty was food that a dog belonging to one of the garrison officers was killed and eaten.

Herbert speaks in glowing terms of the efforts of two American 'Fathers', Heath and Sorry, who were allowed to visit the prison, to soften the lot of the captives. Finally, on March 15, 1779, Herbert was exchanged after two years and four months' captivity.

In a table at the end of his account, he states that between June 1777, and March 1779, there were 734 Americans in Mill Prison, of whom thirty-six died, 102 escaped, and 114 joined the British service. Of these last, however, the majority were British subjects

In 1780, John Howard reported:

In the Mill-prison near Plymouth, there were two hundred and ninety-eight American prisoners on the 3d of February 1779. Their wards and court were spacious and convenient, and their bread, beer, and meat good.

There were three hundred and ninety-two French prisoners. The wards and courts in which they were confined, are not so spacious as those appropriated to the American prisoners, nor were they so well accommodated with provisions. The hospital, which had sixty patients in it, was dirty and offensive, and I found there only three pair of sheets in use. Here a new prison was building. The wards in this new Hospital will be too low and too close, they being only seventeen feet ten inches wide, and ten feet high.

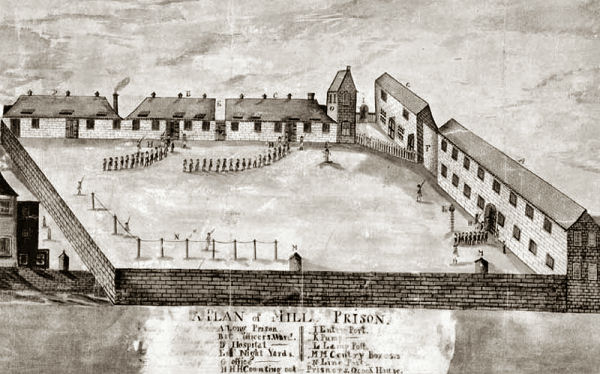

Mill Prison, Plymouth, Devon, late 18th century.

In 1799 Mill Prison was virtually rebuilt and became known as Millbay. Its condition at that time seems to have been very bad. It was said that some of the inmates were so weak for lack of proper food that they fell from their hammocks and broke their necks, that supplies of bedding and clothing were only to be had from 'capitalists' among the prisoners, who had bought them from the distribution officers and sold them at exorbitant rates.

In 1806, at the instance of some Spanish prisoners in Millbay, a firm of provision contractors was heavily fined after it was proved that for a long time past they had systematically sent in stores of deficient quality.

In 1807 the Commissioners of the Transport Office refused an application that French prisoners at Millbay should be allowed to manufacture worsted gloves for Her Majesty's 87th Regiment, on the grounds that, if allowed, it would seriously interfere with our own manufacturing industry, and further, would lead to the destruction by the prisoners of their blankets and other woollen articles in order to provide materials for the work.

In 1809 the Transport Office, in reply to French prisoners at Millbay asking leave to give fencing lessons outside the prison, refused, adding that only officers of the guard were allowed to take fencing lessons from prisoners, and those in the prison.

In 1811 a dozen prisoners daubed themselves all over with mortar, and walked out unchallenged as masons. Five were retaken. Another man got away by painting his clothes like a British military uniform.

In 1812, additional buildings to hold 2,000 persons were erected at Millbay.

During the Crimean War (1853-6), Millbay was used to house Russian prisoners.

from the late 1850s, the prison site was used as a military barracks as shown on the 1863 map below.

Mill Prison site, Plymouth, c.1863.

On 22 June 1911, the day of the coronation of George V and Queen Mary, Millbay recreation ground was opened on the site in 1911.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Has Registers of Prisoners of War held at Norman Cross.

- FindMyPast has an extensive collection of Prisoner of War records from the National Archives covering both land- and ship-based prisons (1715-1945).

Bibliography

- Abell, Francis Prisoners of War in Britain 1756 to 1815 (1914, OUP)

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.