Gaol for Liberty of Havering, Romford, Essex

The Liberty of Havering-atte-Bower comprised the three parishes of Havering, Hornchurch, and Romford. The Liberty had its own gaol from at least 1259, probably located in the Market Place and sharing premises with the Liberty court house. In the 16th century, the gaol was known as the Round House. The gaol and court house were rebuilt in 1737-40 and repaired in 1767-8. In 1747, a room in the gaol was reassigned for use as a Bridewell, or House of Correction.

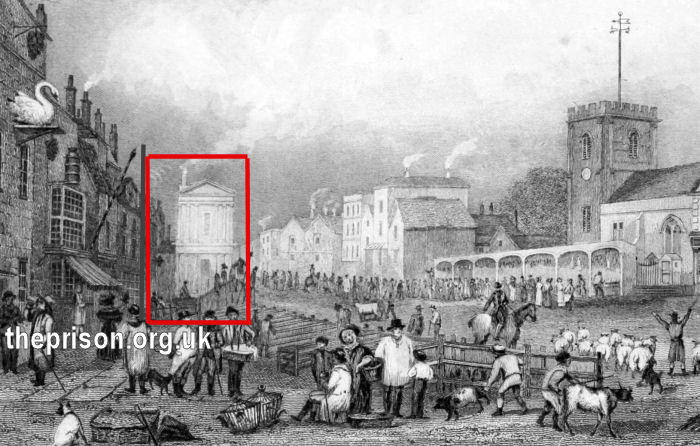

By 1815, the existing building was in a bad condition. Construction of a new gaol and court house, or a major reconstrion of the old premises, took place in 1815-16 was erected at the south side of Romford Market-Place, at the corner of South Street. The gaol, together with a 'cage', were located beneath the court house. In the 1831 illustration below, the court/gaol building is indicated by the red oblong.

Liberty Gaol (highlighted), Romford, 1831.

In 1845, the Inspectors of Prisons reported:

This gaol for the Liberty of Havering-atte-Bower, with a population in all of about 7000 persons, consists of four Cells under the Courthouse, in the town of Romford, which flanks on one side the main street, and on the other a narrower one, the entrance to it being at the end. The whole building is the property of the lord of the manor, and was erected in 1815, at an expense of about 4000l., defrayed from the liberty funds. The gaol is under the jurisdiction of three justices for the liberty, one of whom is the high steward, the others being also magistrates for the county. The liberty has the privilege of quarter sessions, and petty sessions are held once a fortnight. The gaol is professedly a prison as well for debtors as for criminals, there being a debtors' court, termed "court of ancient demesne," attached to the Liberty; but the prison is in no one respect adapted for the last, and has no accommodation whatever for the first, who have consequently been hitherto lodged in the gaoler's private house a quarter of a mile distant, he having no official residence assigned to him in the prison, as required by law. The gaoler, who is also crier of the court, receives for the joint offices a yearly salary of 54l. 12s. He has held the appointment during the last nineteen years, and appears to be a humane and an intelligent man. He was formerly under-bailiff of the liberty.

The situation of the four cells constituting the gaol is extraordinary. They are detached, two and two, at opposite ends of the building, and constructed in such wise that each has free communication with the street by means of the window. Those at the front end, the approach to which is through the court-house entrance, are raised a few feet above the level of the street; the others, on the contrary, being upon a level with it, and consequently less dry than the former. The intervening space across the entire width of the building is likewise level with the street, and opens to it on either side. A square portion, about two-thirds, of this space, is enclosed from top to bottom within an iron railing, and used on market-days as a stand for a butcher's stall, to whom it is let. The remaining portion forms an open passage running parallel with the rear cells from street to street, there being a right of way through it. The doors of these cells open directly into this passage, and are surmounted by open iron-barred windows looking into it, so that nothing is more easy than for a person walking in the street to step into the passage and converse through the door or the window with the prisoners within the cells; and this we ascertained to be a matter of common occurrence. On the other hand, the window of one of the front-end cells looks into the narrow street, and faces a baker's shop only 10 feet from it on the opposite side of the way; whilst that of the other looks into the railed square space, commanding thence a complete view of what is passing in the main street. The angle of the line of view from this window takes in a corner of the passage or causeway, which corner passers-by are in the habit of using for a necessary purpose, and as female prisoners frequently occupy the cell, gross indecencies may obviously be practised. The bars of this window are two inches apart, so that various articles can readily be passed through them whenever the gate of the enclosed space is open. The main bars of the windows of the other cells are likewise two inches apart, but they cannot be used for the same purpose as those of the first, in consequence of a screen of thin iron bars, less than an eighth of an inch apart, being placed either outside or inside, according as the construction permitted, a space equivalent to the depth of the wall intervening between the screen and the bars. Conversation, however, can be carried on with the greatest facility. In fact, the gaoler states that, frequently when he has had prisoners in custody on serious charges, he has only been able to prevent such communication by hiring a man to walk about beneath the prison windows so long as the particular prisoners remained. Those screens did not originally exist, but were put up at the suggestion of the gaoler, who found it impossible otherwise to prevent the practice which prevailed of prisoners obtaining from their friends spirits, tobacco, letters, money, or other articles. But the means taken for the exclusion of these have also had the effect of excluding, to a great extent, both air and light, so that one evil has been replaced by another. None of the cells are glazed, and two only have dark shutters.

The two front-end cells open into a small passage, 6 feet by 3 feet, the entrance door of which faces the door of the main building. One of these cells is 12 feet long, 5 feet wide, and 10 feet high; the other 7 feet 7 inches long, 5 feet wide, and 9 feet high. The roofs are slightly arched at the ends. The floors are boarded. There is a privy with a covered top in each cell. That in the larger one was in a dirty state, and smelt offensively. If only one of the cells be occupied at a time, the door is left open, so that the prisoner or prisoners may have the range of the other cell and the passage. The inside of the passage door, as well as both the outside and inside of the door of the smaller cell, are carved all over with names and dates, a convincing proof of the prisoners having been allowed an improper use of knives. Each of the two cells contains an iron bedstead screwed to the floor, a straw mattress, and four blankets. Both the cells and the bedding were in a very dirty state. The two rear cells are each 15 feel long, 8 feet wide, and 9 feet high, and are boarded. In one, a portion of the floor, 7 feet by 3 feet 10 inches, is partitioned off as a bed, by means of a wooden framework a few inches deep. In the other, a raised wooden bench running down it along one of the walls, serves indifferently as a bedstead, seat, or table. The only bedding in either was some loose straw and a couple of blankets. The back wall of one was in a very damp state. This wall has a window with open iron bars which looks into a narrow gulley intervening between the rear of the prison and the side wall of a house fronting the main street, and is closed only by a low slight door opening upon the pavement. The space above the door being entirely open, nothing could be easier than for a person to climb over at night and hold communication with the prisoners, so that both at back and front means of communication exist. In the day-time the gulley is merely used as a place for the shutters of the house-shop. Within the last three years these two cells have been given up as police cells to a branch of the Essex constabulary police force, and the keys are kept by them; but the gaoler admits that, should circumstances require it, he should still use them for his prisoners, so that in fact they may be used indiscriminately for both purposes. The cells were assigned to the police in order to save the expense of building a station. In one of them, between the bars above the doors, we found the bowl-ends of two tobacco pipes which had been smoked. Now, independent of the infraction of the law, the use of pipes in this cell, where the bedding is loose straw, was positively dangerous. There was no prisoner of any kind in custody at the time of inspection. The gaoler states that the only prisoners he now receives are those awaiting examination or remanded for further examination, and prisoners summarily convicted whose terms of imprisonment do not exceed a week. But the gaoler states that, practically, the terms of imprisonment rarely exceed three days. Prisoners for trial at the sessions are stated to be sent to the gaol at Ilford, in the custody of the police, and brought back from thence by the governor of that prison, when, if convicted, they are again conveyed to Ilford by the police direct from the dock. If for trial at the assizes, they are still sent to Ilford, except that, should the assizes be about to commence they are sent at once to Chelmsford, in order to save expense. The liberty magistrates contract with the magistrates of these two prisons for the support of their prisoners at the rate of 1s. per day. A total of 51 prisoners were thus sent to Ilford gaol in the year ending at Michaelmas last. The legal classification of prisoners is not observed, or professed to be so; indeed the profession would be futile. The greatest number of prisoners in confinement at any one time in the year 1843-44, was six males. Hence it is obvious that if the two police cells were not made use of, these six prisoners must have been crammed together in the two still smaller gaol cells; while, at all events, two or more must have been together in one cell. In January last, two male prisoners who were in confinement here two days, occupied the same cell and slept together in the same bed. This, we need scarcely observe, is a flagrant violation of the Act 4 Geo. IV. c. 64, sec. 10, r. 18. The gaoler admitted, however, that the circumstance frequently occurred, and was sometimes unavoidable. In March last, a woman sentenced to three days' imprisonment, under summary conviction for drunkenness, passed that time in the cell which looks into the railed market-place. Her only attendant was the gaoler. This cell, in common with the others, is wholly without the means of warmth, and the window being unglazed, the woman must have suffered intensely from the cold. She could have put up the shutter, it is true, but then she would have been in darkness, as it is without even a bull's eye. The gaoler said that she kept herself as warm as she could by remaining in bed with her clothes on, and that he occasionally allowed her to warm herself at the court-house fire when no one was there.

In the year ending at Michaelmas, 1843, the number of prisoners committed to this gaol, exclusive of those sent to Ilford and Chelmsford, was 15, of whom two were females; and in that ending at Michaelmas last, 17, of whom one was a female. Of the latter, seven could neither read nor write, four could read only, five could read imperfectly, and one could read and write well. According to the Gaoler's Committal Book,—which, with the exception of a Fine Book, is the only book he keeps,—the number of prisoners in his custody, from the 1st October, 1844, to the 10th April, 1845, was 44 males and 3 females. They were of the following descriptions, viz.,—

| Refusing to work in Union workhouse | 15 |

| Destroying clothes in ditto | 2 |

| Game Laws | 3 |

| Stealing | 14 |

| Assaults | 5 |

| Deserting their families | 3 |

| Other minor offences | 5 |

| Total | 47 |

They were thus disposed of:—

| Convicted and scut to Ilford Gaol for periods varying from 10 days to 3 months | 33 |

| Sent to Chelmsford for trial at the assizes | 7 |

| Released on bail | 3 |

| Sentenced to imprisonment in Romford Gaol — two, two days; one, three days | 3 |

| Committed to Romford Gaol, and acquitted the next day | 1 |

The "Committal Book" records the prisoner's name—offence—in whoso custody—date of "Committal Book" examination—when committed—for what period—where to be tried—how disposed of name and residence of prosecutor.

We have mentioned that it has been the practice for debtors committed to this prison to be Debtors, paid him 10l. a-year for the rent of it; but since the passing of the Act 7 and 8 Vic., c. 56, amending the law of insolvency, they have given it up, deeming it no longer needed, as the debtors had been practically limited to the class coming within the meaning of the 57th clause. Should, however, an exceptional case arise (and the gaoler said this was not impossible), there would be no place to confine the prisoner in. It would be, however, the business of the sheriff, not the keeper, to provide for his safe custody. The debtors committed were chiefly mechanics and labourers; and the gaoler has sometimes had a debtor of this class in his, house for weeks together for a debt of a few shillings. When the debts were of small amount, and the debtors persons whom he knew, and in whom he had confidence, he put no restraint upon their conduct, allowing them to work or walk unwatched in his garden; and he states that this privilege was never abused. He admitted that he ran a great risk; but said he was willing to incur it. The one room in which the debtors lodged was over the kitchen, and approached by a staircase from the latter. The window looked into the garden, and was but a few feet from the ground. It remained for a long time without any bars, until a circumstance occurred which led the gaoler to deem it prudent to have some put up. His servant one day overheard a debtor tell his wife, who had come to visit him, that he intended to get away that night by the window, in order that he might attend Fairlop fair; hut as he merely wished to enjoy himself, and not to escape, he should return in a coupe of days. His intention was, of course, frustrated. Two debtors have occupied the same room and bed together.

There were three debtors committed in 1843 and two in 1844. One was in custody when the new Act came into operation, who might have been liberated under it; but his friends paid his debt and costs.

The gaoler contracts to supply the prisoners' food, debtors as well as criminals, at the rate of 6d. per head per diem; and for this he provides a two-pound loaf, a quarter of a pound of cheese, and a pint of table beer. In cold weather the prisoners are allowed something extra, at the gaoler's discretion, as warm tea or coffee, warm beer, butter, &c.; and for these he is paid in addition. Untried prisoners and debtors are allowed to provide themselves, and to receive what their friends may bring them. The prisoners are stated to be never put upon a bread-and-water diet under any circumstances; and no punishments of any kind are inflicted. There are no prison regulations. Prisoners of all kinds are allowed to see visitors daily till dark. The cleaning and prison washing are done by hired labour for the purpose, two or three times a-year. No provision is made for the prisoners to wash and clean themselves; the gaoler, however, when asked, supplies them with a bucket of water, and lends them soap and a towel. There is no chaplain, nor any means afforded of religious or moral instruction. Sometimes the gaoler lends the prisoners a Testament or Prayer-Book of his own. If a surgeon is required he is sent for, and paid accordingly; but the necessity is stated seldom to arise, and no deaths have occurred. As no one sleeps upon the premises, the prisoners are left entirely to themselves at night; they might, however, make themselves heard from the windows by the police when the latter go their rounds; and when they themselves have prisoners they are said to keep about the prison; but they have no station on the spot or elsewhere.

The total expenses of this gaol for the year ending at Michaelmas last was 163l. 11s. 10d.; and the amount of fines received by the gaoler, and paid to the account of the liberty funds, 14l. 9s. l0d.

Considering the utter unfitness of this prison for the reception of any class of prisoners whatever, we have no hesitation in expressing our conviction that it ought to he forthwith entirely abolished; that all prisoners, still liable to be committed to it, should be sent, instead, to the gaol at Ilford or at Chelmsford; and that such number of proper cells as may be deemed necessary for police prisoners should he built.

Despite its faults, the gaol remained in use as a lock-up until the new police station, also in South Street, was opened in 1894. The gaol building no longer survives.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Essex Record Office, Wharf Road Chelmsford CM2 6YT. Holdings include: Annual returns to the Home Secretary of the numbers of prisoners confined in the gaol, the punishments inflicted, the cost of maintenance, etc.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Has a wide variety of crime and prison records going back to the 1770s, including calendars of prisoners, prison registers and criminal registers.

- Find My Past has digitized many of the National Archives' prison records, including prisoner-of-war records, plus a variety of local records including Manchester, York and Plymouth. More information.

- Prison-related records on

Ancestry UK

include Prison Commission Records, 1770-1951

, and local records from London, Swansea, Gloucesterhire and West Yorkshire. More information.

- The Genealogist also has a number of National Archives' prison records. More information.

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.