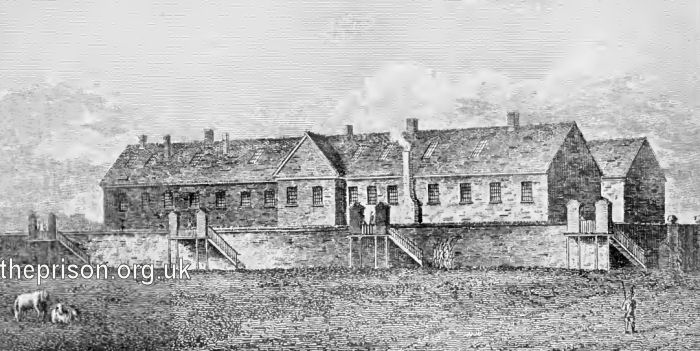

Prisoner of War Camp, Stapleton, Bristol

In 1914, Francis Abell wrote:

Bristol, as being for so many centuries the chief port of western England, always had her full quota of prisoners of war, who, in the absence of a single great place of confinement, were crowded away anywhere that room could be made for them. Tradition says that the crypt of the church of St. Mary Redclliff was used for this purpose, but it is known that they filled the caverns under the cliff itself, and that until the great Fishponds prison at Stapleton, now the workhouse, was built in 1782, they were quartered in old pottery works at Knowle, near Totterdown and Pile Hill, on the right-hand side of the road from Bristol, on the south of Firfield House.

In volume XI of Wesley's Journal we read:

'Monday, October 15, 1759, I walked up to Knowle, a mile from Bristol, to see the French prisoners. About eleven hundred of them, we were informed, were confined in that little place, without anything to lie on but a little dirty straw, or anything to cover them but a few foul thin rags, either by day or night, so that they died like rotten sheep. I was much affected, and preached in the evening. Exodus 23, verse 9. £18 was contributed immediately, which was made up to £24 the next day. With this we bought linen and woollen cloth, which was made up into shirts, waistcoats, and breeches. Some dozens of stockings were added, all of which were carefully distributed where there was the greatest want. Presently after, the Corporation of Bristol sent a large quantity of mattresses and blankets, and it was not long before contributions were set on foot in London and in various parts of the Kingdom.'

But it was to be the same story here as elsewhere of gambling being the cause of much of the nakedness and want, for he writes:

'October 24, 1760. I visited the French prisoners at Knowle, and found many of them almost naked again. In hopes of provoking others to jealousy I made another collection for them.'

In 1779 John Howard visited Knowle on his tour of inspection of the prisoners of England. He reported that there were 151 prisoners there, 'in a place which had been a pottery', that the wards were more spacious and less crowded than at the Mill Prison at Plymouth, and that in two of the day rooms the prisoners were at work — from which remark we may infer that at this date the industry which later became so notable a characteristic of the inmates of our war-prisons was not general. The bread, he says, was good, but there was no hospital, the sick being in a small house near the prison, where he found five men together in a dirty and offensive room. In 1782 the prison at Fishponds, Stapleton, was built. Howard visited it in that year, and reported that there were 774 Spaniards and thirteen Dutchmen in it, that there were no chimneys to the wards, which were very dirty, as they were never washed, and that an open market was held daily from 10 to 3. In 1794 there were 1,031 French prisoners at Stapleton, of whom seventy-five were in hospital. In 1797 the ferment among the prisoners caused by reports of the success of Tate's 'invasion' at Fishguard, developed into an open riot, during which a sentry fired and accidentally killed one of his comrades. Tradition says that when the Bristol Volunteers were summoned to take the place of the Militia, who had been hurried away to Fishguard, as there could be found no arms for them, all the mop-sticks in Bristol were bought up and furnished with iron heads, which converted them into very respectable pikes. It was on this occasion that, in view of the desperate feeling among the prisoners and the comparative inefficiency of their guards, it was suggested that all the prisoners should be lowered into the Kingswood coal-pits!

In 1799 the prison was enlarged at the contract price of £475; the work was to be done by June 1800, and no Sunday labour was to be employed, although Sanders, of Pedlar's Acre, Lambeth, the contractor, pleaded for it, as a ship, laden with timber for the prison, had sunk, and so delayed the work. In 1800 the following report upon the state of Stapleton Prison was drawn up and published by two well-known citizens of Bristol, Thomas Batchelor, deputy-governor of St. Peter's Hospital, and Thomas Andrews, a poor-law guardian:

'On our entrance we were much struck with the pale, emaciated appearance of almost every one we met. They were in general nearly naked, many of them without shoes and stockings, walking in the Courtyard, which was some inches deep in mud, unpaved and covered with loose stones like the public roads in their worst state. Their provisions were wretched indeed; the bread fusty and disagreeable, leaving a hot, pungent taste in the mouth; the meat, which was beef, of the very worst quality. The quantity allowed to each prisoner was one pound of this infamous bread, and ½lb. of the carrion beef weighed with its bone before dressing, for their subsistence for 24 hours. No vegetables are allowed except to the sick in the hospital. We fear there is good reason for believing that the prices given to the butcher and baker are quite sufficient for procuring provisions of a far better kind. On returning to the outer court we were shocked to see two poor creatures on the ground leading to the Hospital Court; the one lying at length, apparently dying, the other with a horse-cloth or rug close to his expiring fellow prisoner as if to catch a little warmth from his companion in misery. They appeared to be dying of famine. The majority of the poor wretches seemed to have lost the appearance of human beings, to such skeletons were they reduced. The numbers that die are great, generally 6 to 8 a day; 250 have died within the last six weeks.'

After so serious a statement made publicly by two men of position an inquiry was imperative, and 'all the accusations were [it was said] shown to be unfounded'. It was stated that the deaths during the whole year 1800 were 141 out of 2,900 prisoners, being a percentage of 4¾; but it was known that the deaths in November were forty-four, and in December thirty-seven, which, assuming other months to have been healthier would be about 16 per cent., or nearly seven times the mortality even of the prison ships. The chief cause of disease and death was said to be want of clothing, owing to the decision of the French Government of December 22, 1799, not to clothe French prisoners in England; but the gambling propensities of the prisoners had even more to do with it. 'It was true,' said the Report of the Commission of Inquiry, 'that gambling was universal, and that it was not to be checked. It was well known that here, as at Norman Cross, some of the worst gamblers frequently did not touch their provisions for several days. The chief forms of gambling were tossing, and deciding by the length of straws if the rations were to be kept or lost even for weeks ahead. This is the cause of all the ills, starvation, robbery, suicide, and murder.' But it was admitted that the chief medical officer gave very little personal attention to his duties, but left them to subordinates.

It was found that there was much exaggeration in the statements of Messrs. Batchelor and Andrews, but from a modern standard the evidence of this was by no means satisfactory. All the witnesses seem to have been more or less interested from a mercantile point of view in the administration of the prison, and Mr. Alderman Noble, of Bristol, was not ashamed to state that he acted as agent on commission for the provision contractor, Grant of London.

Messrs. Batchelor and Andrews afterwards publicly retracted their accusations, but the whole business leaves an unpleasant taste in the mouth, and one may make bold to say that, making due allowance for the embellishment and exaggeration not unnaturally consequent upon deeply-moved sympathies and highly-stirred feelings, there was much ground for the volunteered remarks of these two highly respectable gentlemen.

In 1801, Lieutenant Ormsby, commander of the prison, wrote to the Transport Board:

'Numbers of prisoners are as naked as they were previous to the clothing being issued. At first the superintendants were attentive and denounced many of the purchasers of the clothing, but they gradually got careless. We are still losing as many weekly as in the depth of winter. The hospital is crowded, and many are forced to remain outside who ought to be in.'

This evidence, added to that of commissioners who reported that generally the distribution of provisions was unattended by any one of responsible position, and only by turnkeys — men who were notoriously in league with the contractors — would seem to afford some foundation for the above-quoted report. About this time Dr. Weir, the medical inspection officer of the Transport Board, tabulated a series of grave charges against Surgeon Jeffcott, of Stapleton, for neglect, for wrong treatment of cases, and for taking bribes from the prison contractors and from the prisoners. Jeffcott, in a long letter, denies these accusations, and declares that the only 'presents' he had received were' three sets of dominoes, a small dressing box, four small straw boxes, and a line of battle ship made of wood,' for which he paid. The result of the inquiry, however, was that he was removed from his post; the contractor was severely punished for such malpractices as the using of false measures of the beer quart, milk quart, and tea pint, and with him was implicated Lemoine, the French cook.

That the peculation at Stapleton was notorious seems to be the case, for in 1812 Mr. Whitbread in Parliament 'heartily wished the French prisoners out of the country, since, under pretence of watching them, so many abuses had been engendered at Bristol, and an enormous annual expense was incurred.'

In 1804 a great gale blew down part of the prison wall, and an agitation among the prisoners to escape was at once noticeable. A Bristol Light Horseman was at once sent into the city for reinforcements, and in less than four hours fifty men arrived — evidently a feat in rapid locomotion in those days!

From the Commissioners' Reports of these times it appears that the law prohibiting straw plaiting by the prisoners was much neglected at Stapleton, that a large commerce was carried on in this article with outside, chiefly through the bribery of the soldiers of the guard, who did pretty much as they liked, which, says the report, was not to be wondered at when the officers of the garrison made no scruple of buying straw-plaited articles for the use of their families.

As to the frequent escapes of prisoners, one potent cause of this, it was asserted, was that in wet weather the sentries were in the habit of closing the shutters of their boxes so that they could only see straight ahead, and it was suggested that panes of glass be let in at the sides of the boxes.

The provisions for the prisoners are characterized as being 'in general' very good, although deep complaints about the quality of the meat and bread are made.

'The huts where the provisions are cooked have fanciful inscriptions over their entrances, which produce a little variety and contribute to amuse these unfortunate men.'

All gaming tables in the prison were ordered to be destroyed, because one man who had lost heavily threw himself off a building and was killed; but billiard tables were allowed to remain, only to be used by the better class of prisoners. The hammocks were condemned as very bad, and the issue of the fish ration was stopped, as the prisoners seemed to dislike it, and sold it.

In 1805 the new prison at Stapleton was completed, and accommodation for 3,000 additional prisoners afforded, making a total of 5,000. Stapleton was this year reported as being the most convenient prison in England, and was the equivalent of eight prison-ships.

In 1807 the complaints about the straw-plaiting industry clandestinely carried on by the Stapleton prisoners were frequent, and also that the prison market for articles manufactured by the prisoners was prejudicial to local trade.

Duelling was very frequent among the prisoners. On March 25, 1808, a double duel took place, and two of the fighters were mortally wounded. A verdict of manslaughter was returned against the two survivors by the coroner's jury, but at the Gloucester assizes the usual verdict of 'self-defence' was brought in. In July 1809 a naval and a military officer quarrelled over a game of marbles; a duel was the result, which was fought with sticks to which sharpened pieces of iron had been fixed, and which proved effective enough to cause the death of one of the combatants. A local newspaper stated that during the past three years no less than 150 duels had been fought among the prisoners at Stapleton, the number of whom averaged 5,500, and that the coroner, like his confrères at Dartmoor and Rochester, was complaining of the extra work caused by the violence of the foreigners.

In 1809 a warder at Stapleton Prison was dismissed from his post for having connived at the conveyance of letters to Colonel Chalot, who was in prison for having violated his parole at Wantage by going beyond the mile limit to meet an English girl, Laetitia Barrett. Laetitia's letters to him, in French, are at the Record Office, and show that the Colonel was betrayed by a fellow prisoner, a rival for her hand.

In 1813 the Bristol shoemakers protested against the manufacture of list shoes by the Stapleton prisoners, but the Government refused to issue prohibiting orders.

Forgery was largely practised at Stapleton as in other prisons, and in spite of warnings posted up, the country people who came to the prison market were largely victimized, but Stapleton is particularly associated with the wholesale forgery of passports in the year 1814, by means of which so many officer prisoners were enabled to get to France on the plea of fidelity to the restored Government. In this year a Mr. Edward Prothero of 39, Harley Street, Bristol, sent to the Transport Office information concerning the wholesale forgery of passports, in the sale of which to French officers a Madame Carpenter, of London, was concerned.

The signing of the Treaty of Paris, on May 30, 1814, stopped whatever proceedings might have been taken by the Government with regard to Madame Carpenter, but it appears that some sort of inquiry had been instituted, and that Madame Carpenter, although denying all traffic in forged passports, admitted that she was on such terms with the Transport Board on account of services rendered by her in the past when residing in France to British prisoners there, as to be able to ask favours of it. The fact is, people of position and influence trafficked in passports and privileges, just as people in humbler walks of life trafficked in contracts for prisons and in the escape of prisoners, and Madame Carpenter was probably the worker, the business transactor, for one or more persons in high place who, even in that not particularly shamefaced age, did not care that their names should be openly associated with what was just as much a business as the selling of legs of mutton or pounds of tea.

In spite of what we have read about the misery of life at Stapleton, it seems to have been regarded by prisoners elsewhere as rather a superior sort of place. At Dartmoor, in 1814, the Americans hailed with delight the rumour of their removal to Stapleton, well and healthily situated in a fertile country, and, being near Bristol, with a good market for manufactures, not to speak of its being in the world, instead of out of it, as were Dartmoor and Norman Cross; and the countermanding order almost produced a mutiny.

It appears that dogs were largely kept at Stapleton by the prisoners, for after one had been thrown into a well it was ordered that all should be destroyed, the result being 710 victims ! They were classed as 'pet' dogs, but one can hardly help suspecting that men in a chronic state of hunger would be far more inclined to make the dogs feed them than to feed dogs as fancy articles.

It is surprising to read that, notwithstanding the utter irreligion of so many French prisoners in Britain, in more than one prison, at Millbay and Stapleton for instance, Mass was never forgotten among them. At Stapleton an officer of the fleet, captured at San Domingo, read the prayers of the Mass usually read by the priest; an altar was painted on the wall, two or three cabin-boys served as acolytes, as they would have done had a priest been present, and there was no ridicule or laughter at the celebrations.

After the declaration of peace in 1815, the raison d'être of Stapleton as a war-prison of course ceased. In 1833 it was bought by the Bristol Poor-Board and turned into a workhouse.

Stapleton War Prison, Bristol.

Manor Park Hospital, Bristol, 2011. © Peter Higginbotham

Manor Park Hospital, 2001. © Peter Higginbotham

Manor Park Hospital, 2001. © Peter Higginbotham

The Stapleton workhouse later became Manor Park Hospital. The buildings have now been converted to residential use.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Has Registers of Prisoners of War held at Stapleton.

- FindMyPast has an extensive collection of Prisoner of War records from the National Archives covering both land- and ship-based prisons (1715-1945).

Bibliography

- Abell, Francis Prisoners of War in Britain 1756 to 1815 (1914, OUP)

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.