Female Convict Life at Woking — I.

This is part one of a three-part article by F.W. Robinson published in August 1889 on life in the Woking Female Convict Prison. The accompany illustrations were by Paul Renouard. (Part Two and Part Three are on separate pages.)

Her Majesty's Convict Prisons at Woking, for male and female, lie some two or three miles from the railway station, and are well out of the way of the They are perched upon the higher elevation of general traffic. Knapp Hill, and surrounded by quite a little population of their own, all more or less connected with prison service. Here are the residences of Governors and Deputy-Governors, surgeons and doctors, Superintendents and Deputy-Superintendents, stewards, engineers, together with various humbler quarters for subordinate officers.

Outside the prison in the daytime the place is very quiet, they are country quarters there. A stranger passing through this prison colony attracts as much attention from the good folk at home as he would do in passing through a remote Surrey village; he is not native to the place, or belonging to the prison, and hence is an object of curiosity, till he is out of range. It is quieter than ever at Knapp Hill, we are the only passengers by the little hump-backed cupboard on wheels that lands us in a cramped and crumpled condition at the prison gates. "This Buss (sic) passes the shop," is marked up inside the smallest omnibus in England, although the "shop" applies to a chemist of advertising proclivities in the neighbourhood, and has no facetious reference to the convict settlement hereabouts.

Nothing of a facetious character is attempted Woking-way; there are on the contrary the elements of innumerable tragedies in this pretty rural spot — giant prison houses, private and public lunatic asylums, broad acreages of burial grounds, and a neat crematorium, all asserting themselves in far from a cheerful manner. It is a colony of wasted lives and dead hopes, take it altogether. One is not very much surprised at the stillness in the place, although the omnibus-driver blows his horn as he rattles through the felons' settlement in the hope of a chance fare.

This prison portion of Woking is quieter than we have known it hitherto, for the male portion — and thank God for it — is out of work and out of gear. The male prisoners have gone their various ways; they were semi-invalids and lunatics, the majority of them, and worked very much in the open on the farm-land, or at the gardens of the principal officers, or at the outside pumps, and gangs of men, attended by armed warders, were frequently to be encountered marching along the high road before they diminished in numbers, or were drafted to other establishments by order of the Board.

They were "balmy," a good many of these convicts, ailing and well-behaved men, most of them, and it has been considered better to consign them to the criminal lunatic prison at Broadmoor for once and all. Some of them we should think were very mad, indeed, and hardly deserving of the fate of penal servitude, unless they have considered it politic to sham a bit. It is not easy to fathom the depths of the convict mind.

One prisoner, who for some time had steadily maintained that he was the Saviour, was asked by a fellow-convict a scoffing question concerning the Virgin Mary. The answer came very quickly back. "Oh! I don't see anything of my mother now," was the reply. "She's over the way, poor thing, in the female division."

There has been one attempt at escape lately. A lunatic prisoner, whilst at work on the farm-land, suddenly quitted his party and took to his heels, in the vain hope of getting clear off. The alarm was quickly given, and a smart chase ensued, the officer in charge of the gang succeeding in running him down and re-capturing him, before the convict quite reached the boundary.

The male prison is almost devoid of convict life now, the wards echo only to the tread of the officers who have "got no work to do," and who are probably waiting orders to be drafted elsewhere; they are glad even to do a little prison labour themselves, of their own free will, and just to wile away the time. The male cells are only full of prison furniture, or stacks of "pints" and cans, and the big work-rooms are desolate of human presence; there are but five convicts in the whole of this big male prison, and they have an upstairs wing to themselves, and must feel very much "hipped" by the absence of congenial society. One wonders who is having the worst or dullest time of it, the prisoners or the prison-warders, at the present time of which we write.

But they are still busy at Her Majesty's Female Convict Prison across the road; there is plenty to do, although numbers have decreased with a most startling and gratifying rapidity of late years. Here, under the able governorship of Dr. Clarke — the only governor of Her Majesty's prisons, we are disposed to think, who is not of a military or naval training, and who is one peculiarly fitted by his profession and by his keen powers of observation for the direction of a female convict establishment — and the vigilant superintendence of Miss Hutchinson, assisted by chief matron Mrs. Price and numerous painstaking officers, are still some four hundred and odd female convicts who are serving out long sentences, and who in many instances are prisoners for life. Four hundred and nine female convicts are the exact figures on this day of our visit; six years before — in the corresponding month, that is, of October, 1882 — there were no less than 624 prisoners to keep watch and ward upon. This is a satisfactory decrease indeed, and the philanthropist has a right to rejoice as well as the Prison Board over such welcome statistics as these. The female prison at 7oking is not much more than half full now; for here again we come upon long empty rows of cells, the doors wide open and gaping, and the "pints," and tables, and stools stacked away in orderly pyramids, and no sad, or hard, or cruel, or wan faces to be turned to you from the cages which were a little while ago so full of gaol-birds.

The Female Prison at Woking is constructed to contain 700 women, and it has been in its day overflowing with convicts. It stands on five acres of ground, and has two-and-a-half acres of land surrounding it, where women do farm-work occasionally, and are as glad of the extra exercise and the fresh air, and life in the open, as were the convicts formerly of the male division opposite. To the male prison, it may be remarked, there belong no less than fifty-five acres of land, so that farming operations have been conducted on almost a large scale, considering the class of labour employed.

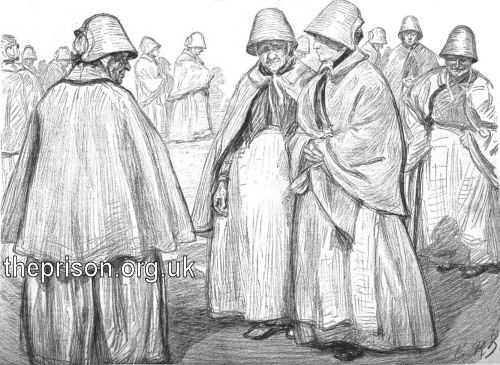

There are a considerable number of invalid female convicts in this prison — indeed, the prison is intended for those who are weak and ailing, or not quite as strong as could be wished. The women out for exercise, and whom M. Renouard has so graphically depicted here, are a fair sample of the aged and feeble convicts who make this place their home, who have been in and out of prison all their lives, and to this "sad complexion," as Randolph has it, have they come at last. It is very near "the end on't" now in many sorrowful instances.

Invalids exercising, Woking Female Prison, 1889.

One woman sitting alone in an infirmary cell looms upon us as a startling prison portrait — so heaped up and helpless and distorted is she — so ghastly in her deformity, and so very, very still! She does not look at us with that curious, questioning, wondering stare common to most convicts when a visitor intrudes; she is not roused to the least sign of interest by a special visit at an unlooked-for time — an entrance and exit are not of the slightest consequence to her — she remains a hunched-up withered figure without a sign of life in her to the end

"Spinal," says the Governor, as we pass out, "a hopeless case."

A few doors from her is a fair-haired, good looking young woman, who does not appear to have much the matter with her, and who is comfortably tucked up in bed, and apparently enjoying her ease very much. She surveys her visitors critically and curiously.

"How are you now?" asks Dr. Clarke.

"Very bad, sir."

"Ah, you'll be all right by to-morrow morning," is the assuring comment to this, but the prisoner does not appear in any way grateful for the information conveyed to her.

This prisoner has never done a fair stroke of work since she has been at Woking, we are informed, and she never intends if she can help it. She is naturally delicate, and she makes the most of it. "I have never been used to work," she has explained more than once to those who have been struck with her dilatoriness, and protested against it, "and I can't get used to it. You must know I have mixed in the very highest spears." The lady is in for a little robbery connected with a disorderly house at Pimlico. "However can I slave like these poor critters here?"

"What spheres have you mixed in?" was the inquiry put to her after this announcement.

"I was a builder's wife first and then a gentleman took care of me," she explained, with charming frankness and with considerable pride as to her antecedents, "and I never thought I should come to this disgrace."

Work goes on, as a rule, with a fair amount of regularity and precision. The women are busy at twine-making — a new feature of convict labour that is progressing very satisfactorily — at post office bags, at making clothing for the Greenwich boys, &c. The tailors' room — a big ward where all the tailoresses are collected — is an imposing scene. They are very industrious until our appearance, when the clicking of innumerable sewing-machines ceases, and a general scramble of female convicts to their feet ensues in compliment to the Governor's special call upon them. At a signal they are again in their places, working with renewed energy, but with their eyes focussing us with grave attention, and the hive is hardly as composed at our departure as upon our entrance. They are not quite certain what we want, or who we are — we may be there for purposes of identification, or on a special mission of inquiry, or from pure motives of philanthropy, or curiosity, and the convicts keep their furtive watch upon us until we have quitted the apartment.

There are less breaking-outs than there used to be in the female convict prisons, we are assured. The new hands seem to have acquired, under the fresh rules, newer and better manners. Here, as at Wormwood Scrubs, we are shown the punishment cells — all empty! And Mrs. Price, the chief matron, picks up from a corner of one cell a hideous-looking article not unlike a diver's dress destitute of bull's-eyes, but festooned with various straps and bands and buckles. It is almost blue-mouldy from disuse, this prison jacket or strait-waistcoat, in which have been "cabined, cribbed, and confined" many a refractory in turn. Quarrels between the women are not as frequent as of yore even, though the "break out common to the female prisoner will occur at times, and the prison be distracted now and then from the even tenor of its way. But these are exceptions to the general rule of prison propriety. The Governor has already shown us his books — what an odd system of human book-keeping by single entry it is! — and in the later pages are records of days without a single report against the women.

Saluting the Matron, Woking Female Prison, 1889.

The female convicts have their little grievances, of course, but they are reasoned out of them frequently, and the odd fancies which one woman takes for another are still prevalent, and are one of the chief causes of dispute and insubordination. Prison "stiffs," i.e., communications of a loving tendency, pass from hand to hand till they reach the person for whom it is intended, and odd and ingenious are still the means by which they correspond. Failing ink or a fly-leaf from the library books, a woman will secure at times a scrap of brown paper from the work-room or elsewhere, and prick with a pin upon it all that she has to communicate. Ingenuity can hardly further go.

In old times here, and in the female convict prisons at Millbank, Brixton, and Parkhurst, there was "something too much of this," and many outbreaks, and occasionally stand-up fights, were the consequence. Women are fickle and changeable in their affections, even in prison, it appears, and are terribly jealous and resentful of an undue preference or a slight.

It was no uncommon experience for an aggrieved woman who had been presented with a lock of hair at some time or other of her prison career, to take this lock from her pocket, most frequently in church, hold it up derisively to her who, in the first instance, had presented it, and affect to wipe her nose with it. Salt sprinkled on a lock of hair returned to the donor is always considered the most grievous and intolerable of insults, and it would lead to much extravagance of action, even to murder, should the chance present itself when the passions of these wild creatures are aroused. And yet these ungovernable natures are not the convicts incarcerated for the worst offences; they are the women from the streets, the women whose sentences have become cumulative owing to sundry dire offences, and who are in and out of prison all their lives, the pickpockets, the receivers of stolen goods, and so forth.

One of the most notable prisoners at Woking was the notorious Madame Rachel. She was an old woman when she began her imprisonment, and she died, if my memory serve me correctly, at Woking before the term of her incarceration had quite expired. Our readers will remember the cause of her offence against the laws — a case of extorting money from a Mrs. Borrodaile, who had submitted to the Jewish woman's process of being made "beautiful for ever." Madame Rachel lived principally in the infirmary, and here, where the rules can never be very rigidly carried out, she would amuse both prisoners and matrons by little anecdotes of her career. She had amassed considerable wealth by trading on the weaknesses and vanities of her sex, and she dropped many significant hints of how she was going to benefit, some early day after her release, all those who had been kind to her in her "present misfortune." Failing to impress any one by this, she would hint at the various secrets she possessed for improving the complexion, &c., and how happy she should be to impart any portion of her valuable information to any one who really wished for it. Her prison life was one persistent attempt to ingratiate herself with the officials — no one took more pains to render herself in every way agreeable. It was not a bad trait of character, but it was accompanied by such odd and barefaced flattery and compliments that the effect was, as a rule, the reverse of that which she had intended. Upon one matron answering "Pretty well, thank you," to an inquiry as to how she was that morning, Madame Rachel said with unction, "Pretty I know you are, well I am very glad to hear."

To another matron, whom she was anxious to conciliate, she discoursed upon her process of enamelling, and the large sums she had made by it. "But there," she concluded, "your splendid complexion, Miss ——, will never require enamelling. Gold cannot purchase anything like that."

Madame Rachel never expressed any contrition for the offence which had rendered her amenable to the law; in her heart of hearts she considered herself a deeply-injured person. She was very proud of her name and the noise she had made in the world; a new comer was informed as soon as it was possible that she was the celebrated Madame Rachel. She was a very ugly old woman, who had not attempted any beautifying experiments on herself, and who was eccentric and full of flattery to the last. A daughter of hers used to come on visiting days — a very handsome young woman, encumbered by much jewellery and gorgeous wearing apparel. Between these two there was apparent a considerable degree of affection; they would meet and part with much exhibition of affection. The daughter became a famous opera singer, whose death, under terrible circumstances, occurred some two years since.

These are a few of the prison characters that have served their "bit of time" within the grim walls of the female convict prison at Woking. The series might be extended to a considerable length were space available. We defer our account of the "lifers" for a future occasion.

We have mentioned prison visits and prison visitors more than once in this article. Here the convict is for awhile off-guard, and here occur many strange scenes, many little flashes of serious drama, light comedy, and roaring farce. The accommodation for the prison visitor at Woking is not of a lavish order, and the space is limited in which to meet. The visitor is ushered into a small room divided into three compartments, in the centre of which is a matron upon duty. Into the furthest division from the visitor, when everything is ready, appears the convict inquired for, and then ensues twenty minutes' of solid, earnest conversation, news of home, news of father and children, news of old pals, hints for the future, carefully-guarded hints at times, which even the matron cannot understand, and which are stopped in consequence, exhortations, reproofs, words of encouragement to keep strong, even heaps of much vigorous abuse, when the feelings are aroused, and one or another loses command of them.

One woman, whose failing health combined with the extenuating circumstances of her crime rendered it probable that she might be let off presently, was very anxious that her father — who had called to see her — should write a letter to the authorities begging for a reconsideration of the case, and a modification of the sentence. She had been a prisoner for twelve and a-half years, but she had been told that no concession was likely to be made to her until she had done at least fifteen years' penal servitude.

The father wrote at his daughter's request, but the woman, upon his next visit, sharply cross-examined her parent, expressed grave doubts of his veracity, said it was all his fault that she had been a prisoner so long, and announced it as her intention from that time forth to pray very heartily every night for his speedy decease. This was far from a satisfactory prison visit, and her father did not remain his allotted twenty minutes on that occasion.

There are times when very odd visitors present themselves at the outer gates to the critical inspection of Mr. Ledger, or who ever may be now doing duty in his place.

Á very amusing instance of this — which was told us a few years ago by an old warder of the Woking staff — may be pertinent to the present subject.

A somewhat shabbily-attired gentleman put in his claim one morning to be admitted into Woking Prison. He had arrived with the necessary order from Parliament Street to see a certain prisoner, but it was clearly apparent to the gate-keeper that the new-comer was in an advanced stage of intoxication. This was somewhat of a novelty, but the warder acted promptly.

"You can't come in, in this state," he informed the applicant for admission.

The man was disputatious, not to say "bumptious."

"What state are you talking about, I should like to know?"

"You're not sober."

"You're very much mistaken about that. You'll have to prove your words, mind you," said the applicant, growing irate, "and you'll get yourself into trouble for disobeying the orders of your superiors. You'll get discharged, see if you don't."

"I shan't let you in," was the short reply.

"Well, then, I demand to see the governor. Where's the governor of this establishment?"

"He's out."

"When will he be in?"

"You can see him at ten o'clock tomorrow morning."

"That won't do for me. I'm not going to wait till to-morrow morning. I shall go before a magistrate at once; there's one sitting at Guildford, you know."

"Yes; that's right."

"Then I shall go and report my case to him. And, mind you," said the man, in a towering passion now, "you have refused me entrance to the prison, although I come furnished with a proper order — it's a very serious look-out for you. Especially — but perhaps you don't know who I am?"

"Can't say I do."

" I thought not. Well, then, I'm a gentleman usher; and I assure you that it is a most serious business at any time to insult a gentleman usher."

The warder was not impressed even by this last announcement, and the man departed in a high state of indignation. The next day he made his second appearance at Knapp Hill, in a similar state of intoxication to that of the previous day. Experience had not rendered him one whit the wiser. He was bland in demeanour, even excessively polite, to begin with, but his second state of inebriety was worse than his first.

"Good morning, sir; I'm back again, you see. It's all right now, of course," he began, "and I may as well say at once that I wish to rectify an error and apologise for a mistake that I fell into yesterday. I stated to you, sir, that I was a gentleman usher. That was a slip of the tongue, unfortunately. I should have said a journeyman hatter!"

But neither apologies nor a general suavity of demeanour could atone for the fact that he was not at that moment a fit object to be introduced into Her Majesty's prison, and permission to enter was again refused, at which second slight, he once more lost command of his temper, and launched forth into indignant expletives until the gate was summarily closed upon him, and he was left in the roadway anathematising everybody connected with convict service.

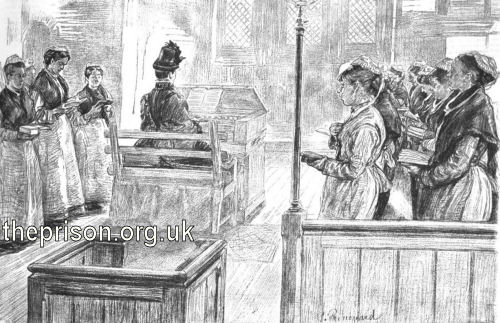

An imposing scene at Woking Prison — as at all prisons by the way — is that of the convicts in chapel. It is more impressive here because the women are numerous, and form a strange and noteworthy congregation. The chapel, or church — it is generally termed chapel by prisoners and matrons — is capable of accommodating some hundreds of convicts, and, although numbers have gone down, the sacred edifice appears fairly full.

In the chapel, Woking Female Prison, 1889.

There is strict order kept, and the women are outwardly decorous and attentive. They sing the hymns and even anthems with some degree of fervour, and as a rule there is but little difference between the decorum here and in places for Divine worship apart from convict life. The women have the body of the chapel to themselves under the supervision of the matrons, and in a gallery above sit the superior officers of the establishment.

The front of the gallery has been somewhat recently painted to imitate woods of a superior quality to the plain pine of which it is constructed. This has been the work of a painter and grainer in durance vile on the male side of the establishment, and the extra ornamentation has been excellently carried out. The walls also have been tinted and relieved of their bareness of exterior since Mrs. Gibson and Miss Stephens, the late lady-superintendent and deputy-superintendent, have passed from authority here.

Still, despite the due amount of reverence exhibited, the matrons are quietly watchful of their flock. Order has not always reigned supreme in prison chapels, and elsewhere; in a future article we shall record some celebrated émeutes at various prisons that have taken place in the old days, and have directed attention to the various ruses which association at chapel-time afford an opportunity sometimes for practising.

For these are not all tame, submissive, gentle, or repentant creatures. The quiet woman has before now gone to church with her tin "pint" smuggled under her shawl, with the fixed intention, should a chance present itself, of battering in the brains of that other woman who has transferred her affections elsewhere, or sent to her by secret messenger some particularly objectionable communication. There in the chapel the prison "stiffs" are circulating from hand to hand, and the lip language — the silent conversation in which many of these women are as great adepts as the poor proficients in our deaf and dumb asylums — is going on in spite of official vigilance. The thoughts are not all of the church, churchy — very much to the contrary, we fear; and the prayers are not in every instance for the better heart and the higher life that the preacher tells them it is in their power to attain.

Here is a prayer with a reserve in it that was heard in Woking Female Prison a few years since, a hearty prayer in its way, but far from complimentary in all its details:—

"Lord, have mercy upon us miserable sinners. Lord, have mercy upon all the miserable sinners here — Lady Superintendent sinners, Deputy-Superintendent sinners, Chaplain and Doctor sinners. Lord, have mercy upon everybody but those beasts of matrons!"

Links

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.