Brixton Prison, London

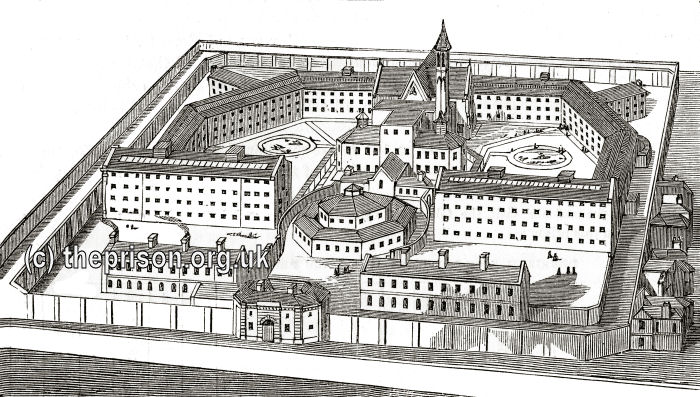

In 1852, the recently closed Surrey County Bridewell on The Avenue (now Jebb Avenue), Brixton, was purchased for £13,000 by the government for use as a women's convict prison. It was intended to house some of the growing number of prisoners sentenced to penal servitude, a replacement for transportation, in which hard labour formed a central part.

The new establishment came into use the following year after alterations and additions had been carried out. The main additions were two new four-storey wings — one at either end of the old crescent-shaped range of buildings — together with a new chapel, laundry, and houses for the superintendent and chaplain. The new wings could each house 212 prisoners, so that the prison accommodation, when these were finished, comprised 158 separate cells, 12 punishment cells, 424 separate sleeping cells, as well as two sets of four association rooms — one at the south-eastern and the other at the south-western angle of the building, and each capable of containing 60 prisoners (15 in each room), or 120 in all. The total accommodation was then sufficient for about 700 prisoners.

Brixton Female Convict Prison, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

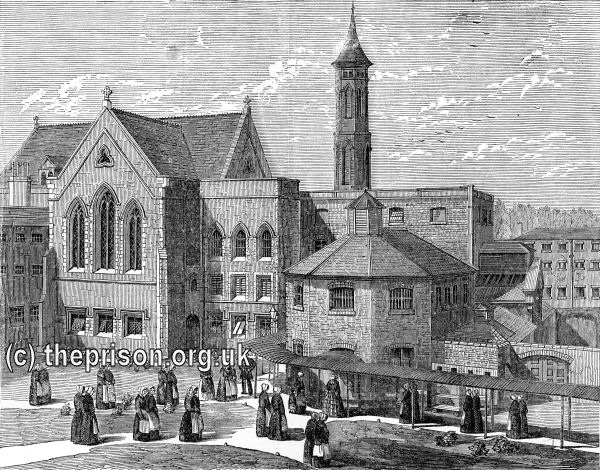

Brixton Female Convict Prison, inmates exercising, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

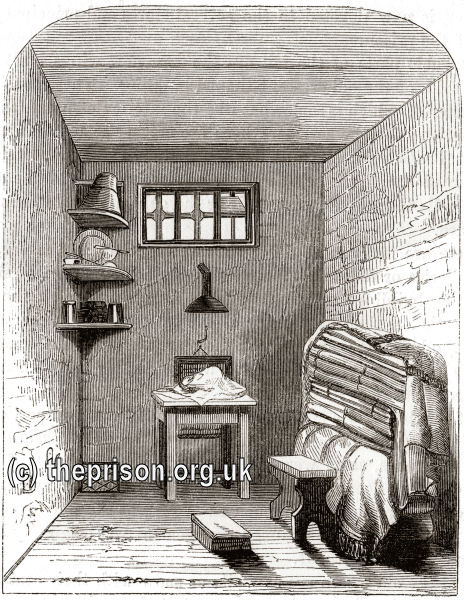

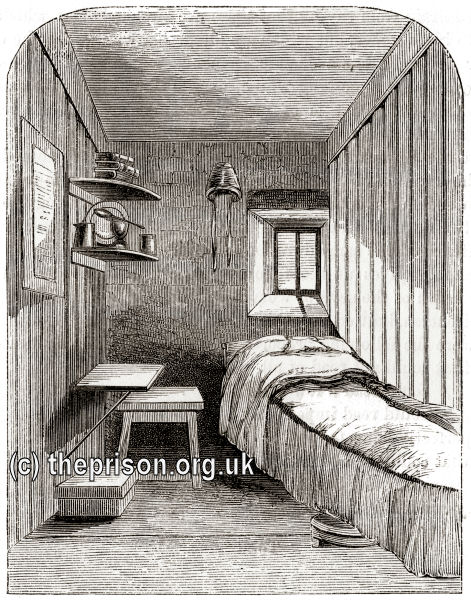

Brixton Female Convict Prison, separate cell in old part of prison, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

It decided that the efficient female officers at Millbank Prison should be transferred to Brixton, and that the female establishment at the former prison should be gradually broken up, all articles that could be used being made available for the latter. By November 1853, there were 75 cells completed and fit for occupation, and that number of females was removed from Millbank to Brixton on the 24th on that month. Those selected for transfer were chosen based on their previous good behaviour and their acquaintance with prison discipline."

An account of the Brixton prison in 1862 reported:

As regards the discipline enforced at Brixton prison, it maybe said to consist of a preliminary stage of separation as a period of probation, and afterwards of advancement into successive stages of discipline, each having superior privileges to those which preceded it; so that whilst the preliminary stage consists of a state of comparative isolation from the world, the female prisoners in the latter stages of the treatment are subject to less and less stringent regulations, and thus pass gradually through states first of what are termed "silent association," under which they are allowed to work in common without speaking, and afterwards advance to a state of association and intercommunication during the day, though still sleeping apart at night.

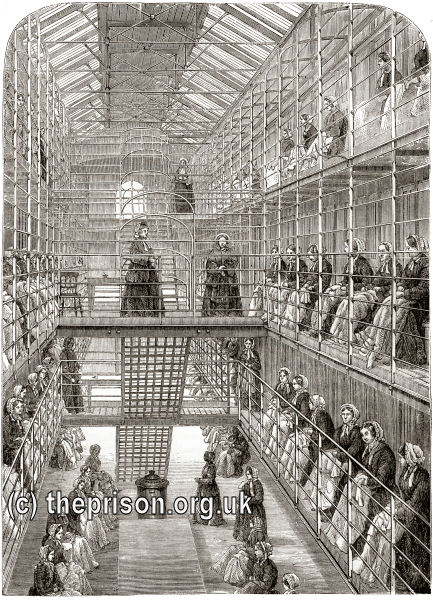

Brixton Female Convict Prison, inmates at work during the silent hour, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

Brixton Female Convict Prison, separate sleeping cell in a new wing of prison, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

The following are the reasons assigned for this mode of treatment: "Until very lately female convicts," the authorities tell us, "were taught to regard expatriation as the inevitable consequence of their sentence; and when detained in Millbank — usually for some months, waiting embarkation — they were reconciled to the discipline, however strict, by the knowledge that it would soon cease, and that it was only a necessary step towards all but absolute freedom in a colony. Now, however, the circumstances being materially altered, and discharge from prison in this country becoming the rule, it is essential that a corresponding change in the treatment of female prisoners should take place, with the view to preparing them to re-enter the world. Hence the necessity for establishing a system commencing with penal coercion, followed by appreciable advantages for continued good behaviour.

"As therefore a systematized classification, denoted by badges, and the placing of small gratuities for industry to the credit of the deserving, have been found by experience in all the convict prisons to produce the most satisfactory results, the same principle has been ex tended to Brixton."

With this view the prisoners there are divided into the following classes:—(1) First Class; (2) Second Class; (3) Third Class; (4) Probation Class.

All prisoners on reception are placed in the probation class, and confined in the cells of the old prison — in ordinary cases for a period of four months, and in special cases for a longer term, according to their conduct; and no prisoner in the probation class is allowed to receive a visit.

On leaving the probation class the prisoner is promoted to the third class, and when she has conducted herself well in that class for the space of two months, she is allowed to receive a visit. Then, if her conduct continue good for a period of six months after promotion to the third class, she is transferred to the second class, and is not only allowed to wear a badge marked 2, as indicative of her promotion, but becomes entitled to a gratuity of from sixpence to eightpence a week for her labour, such gratuity going to form a fund for her on her liberation.

If after this she still continue to behave herself well, while in the second class, for another period of six months, she then is raised into the first class, and allowed to wear a badge marked 1, as well as becoming entitled to a gratuity of eightpence to a shilling a week for her work.

No prisoner is recommended for removal or discharge on license (or ticket-of-leave) until she has proved herself worthy of being intrusted with her liberty previous to the expiration of her sentence.

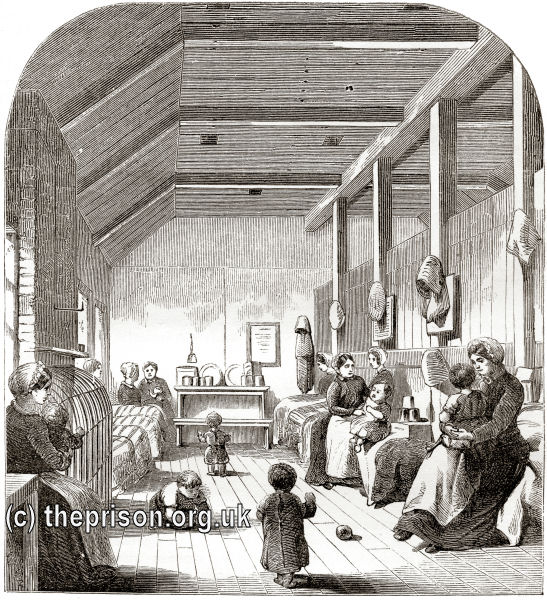

Old or invalid prisoners, or those who have infants, or who, from any other cause, may be unable to work, have their case specially considered (after having gained their promotion to the first or second class), with a view to their being credited with some small weekly gratuity.

Prisoners may be degraded (with the sanction of a director) from a higher to a lower class through misconduct, but their former position may be regained by good conduct, and that without passing the full time in each class over again. All privileges, moreover, for good behaviour, such as gratuities for work, and the permission to receive visits, may be forfeited by bad behaviour.

"The means at our command," add the directors, "for improving, if not actually reforming, female convicts in prison, though carefully designed and faithfully executed, will be in sufficient in many instances unless some asylum be found to receive them on their discharge from prison. The difficulties in the way of such women, as the majority of these prisoners, returning to respectability are too notorious to require description or enumeration. They beset them in every direction the moment they are discharged, and drive them back to their former evil ways and bad associates, if they be not rescued through the medium of a refuge from whence they may obtain service."

Interior of the Brixton Prison.

It was not much after six o'clock when we began our day's rounds at the above institution. The gateway here looks as ordinary and ugly as that of Pentonville appears picturesque and stately, the Brixton portal being merely the old-fashioned arched gateway, with a series of "dabbed" stones projecting round the edge, and the door itself studded with huge nails.

On the gate being opened, we were saluted. in military style by the ordinary prison gate keeper, and shown into the little lodge, or old-fashioned porter's office at the side, where We were soon joined by the principal matron (whom the superintendent had kindly directed to accompany us for the entire day), and requested to follow her to the interior of the building

The matron was habited in what we afterwards learnt was the official costume or uniform belonging to her station; there was, however, so little peculiar about her dress that it was not until we saw the other principal matrons in the same coloured ribbons and gowns that we had the slightest notion that such a costume partook in any way of a uniform character. She wore a dove-coloured, fine woollen dress, with a black-cloth mantle, and straw bonnet, trimmed with white ribbons, such being the official costume of the principal matrons. The uniform of the matrons, on the other hand, consists of the same coloured gown, but the bonnet is trimmed with deep blue, and when in the exercising grounds, the cloak they wear is a large, deep-caped affair, that reaches nearly to the feet, and is made of green woollen plaid.

While treating of this part of the subject, we may add that one of the main peculiarities of Brixton Prison is, that the great body of officials there belong to the softer sex, so that the discipline and order maintained at that institution become the more interesting as being the work of those whom the world generally considers to be ill-adapted for government. So much are we the creatures of prejudice, however, that it sounds almost ludicrous at first to hear Miss So-and-so spoken of as an experienced officer, or Mrs. Such-a-one described as having been many years in the service, as well as to learn that it is some young lady's turn to be on duty that night, or else that another fair one is to act as the night-patrol. Even the posts of superintendents and chaplain's clerks are women; but those who are inclined to smile at such matters should pay a visit to the Female Convict Prison at Brixton, and see how admirably the ladies really manage such affairs.

There is but little architectural or engineering skill to be noticed in the building at Brixton, after the eye has been accustomed to the comparative elegance and scientific refinement visible in the arrangements of Pentonville.

At the end of a large court-yard, as we enter, stands a clumsy-looking octagonal house, that was originally the governor's residence, or "argus," as such places were formerly styled, whence he was supposed to inspect the various exercising yards and sides of the jail itself. This argus, however, is now devoted to the several stores and principal offices required for the management of the prison.

The most remarkable parts of the jail are the two new wings built at the corners, or horns, as we have said, of the old crescent-shaped building. These consist each of one long corridor, the character of which is somewhat like the interior of a tall and narrow terminus to some railway station; for the corridors here are neither so spacious nor yet so desolate looking as those at Pentonville, since at Brixton there are stoves and tables arranged down the centre of the arcades, and the cell-doors are as close as those of the cabins in a ship, to which, indeed, the cells themselves, ranged along the galleries, one after another, bear a considerable resemblance.

But though there are many more doors visible here than at the largest railway hotel, and though the galleries or balconies above, with their long range of sleeping apartments stretching round the building, call to mind the arrangements at the yards of the old coaching inns, nevertheless there is nothing of the ordinary prison character or gloomy look about this part of the building; and though the corridors are built somewhat on the same plan as the arcades at Pentonville, they have a considerably more cheerful look than the apparently tenantless tunnels at that prison.

The old parts of Brixton Prison are the very opposite to the newer portions of it, for in them we see the type of a gloomy and pent-up jail. There the passages are intensely long and narrow — like flattened tubes, as it were — and extend from one point of the crescent to the other, at the back of every floor; the doors of the cells too are heavy cumbrous affairs, with a large perforated circular plate in each, such as is seen at the top of stoves, for admitting or shutting-off the heated air — which clumsy arrangement was originally intended as a means of peeping into the cells from without.

These passages of the old prison are as white as snow with their coats of lime, and seem, from the monotony of their colour and arrangement, to be positively endless, as you pass by door after door, fitted with the same big metal wheel for spying through, and the huge ugly lock of the old prison kind.

The cells in this part of the building are not unlike so many cleanly cellars, with the exception that their roofs are not vaulted, and there is a small "long-light" of a window near the ceiling.

These cells are each provided with a gas-jet and chimney, and triangular shelves, as well as a small stool and table, and a little deal box for keeping cloths in, and which can also be used as a rest for the feet. Then there is a hammock, to be slung from wall to wall, as at Pentonville, and the rugs and blankets of which are usually folded up and stacked against the side, as shown in the annexed engraving.

The cells here are all whitewashed, and as white as Alpine snow, with their coat of lime, so that they try the sight sorely after a time; indeed, we were told that a gipsy woman (one of the Coopers) who was imprisoned here, suffered severely in her eyes from the dazzling whiteness of the walls that continually surrounded her; and if it be true that perpetually gazing at snow has a tendency to produce "gutta serena" in some people, we readily understand the acute pain that must be experienced by those whose sight is unable to bear such intense glare, and from which it is impossible to transfer the eye even up to the blue of the sky by way of a relief. We were informed that the gipsy woman was very violent during her incarceration, and it does not require a great stretch of fancy to conceive the extreme mental and physical agony that must have been inflicted upon such a person, unaccustomed as she had been all her life even to the confinement of a house, and whose eye had been looking upon the green fields ever since her infancy; so that it is not difficult to understand how the four blank white walls for ever hemming in this wretched creature, must have seemed not only to have half-stifled her with their closeness, but almost have maddened her with the intensity of their snow-like glare.

The cells in the east and west wings, though smaller than those in the old part of the prison, have not nearly so jail-like a look about them; for the sides of these are built of corrugated iron, and though fitted with precisely the same furniture as the cells before described, they greatly resemble, as we have said, the cabin of a ship (see engraving on next page), whilst the arrangements made for the ventilation of each chamber are as perfect as they well can be under the circumstances.

Respecting the character of the inmates of this prison, the Government reports furnish us with some curious information. "The prisoners," say the Directors of her Majesty's Convict Prisons, "may generally be classed, as regards their conduct, in two divisions, viz., the many who are good, and the few who are bad. In one or other extreme these unfortunate females have been usually found. It also by no means uncommonly occurs that a woman who has conducted herself for several months outrageously, and been to all appearance insensible to shame, to kindness, to punishment, will suddenly alter and continue without even a reprimand to the end of her imprisonment; whereas, on the other hand, one who has behaved so well as to be put into the first class, and on whom apparently every dependence may be placed, will suddenly break out, give way to uncontrollable passion, and in utter desperation commit a succession of offences, as if it were her object to revenge herself upon herself.

Among the worst prisoners were women who had been sentenced to transportation just previously to the passing of the Act which practically substituted imprisonment in this country for expatriation. A few of these had, according to their own statement, even pleaded guilty for the purpose of being sent abroad; but when they became aware that they were to be eventually discharged in this country after a protracted penal detention, disappointment rendered them thoroughly reckless; hope died within them; they actually courted punishment; and their delight and occupation consisted in doing as much mischief as they could. They constantly destroyed their clothes, tore up their bedding, and smashed their windows. They frequently threatened the officers with violence, though it must be stated, at the same time, they seldom proceeded to put their threats in force; and when they did so, some among them — and generally those who were most obnoxious to discipline — invariably took the officers' part to protect them from personal injury.

"Of these a few are not at all improved, notwithstanding the kindness they have met with, or the punishments they have undergone, or the moral and religious instruction they have received; and they will probably remain so until their sentences have expired. Some, how ever, are doing very well, and give promise of real amendment."

Farther, the medical officer, in his report for the year 1854, says, "I may, perhaps, be here allowed to state that my experience of the past year has convinced me that the female prisoners, as a body, do not bear imprisonment so well as the male prisoners; they get anxious, restless, more irritable in temper, and are more readily excited, and they look forward to the future with much less hope of regaining their former position in life.

"Neither can I refrain from saying that there are circumstances which help to reconcile the male prisoner to his sentence, but which are altogether wanting in the case of the female. The male prisoner not only gets a change from one prison to another — and though small as this change be, yet it is a something which, for the time, breaks the sameness inseparable from his imprisonment — but, what is of far greater moment, he looks forward to the time when he will be employed in the open air on public works.

"The length of the imprisonment of the woman, however, combined with the present uncertainty as to the duration of that portion of her sentence which is to be passed in prison, as well as the more sedentary character of her employment, allowing the mind, as it does, to be continually dwelling on her time' — all tend to make a sentence more severe to the woman, than a sentence of the same duration to the man."

Farther, the chaplain gives us the following curious statistics as to the education and causes of the degradation of the several women who have been imprisoned at Brixton:

"Of the 664 prisoners admitted into this prison from November 24th, 1853, to December 31st, 1854, there were the following proportions of educated and uneducated people:—

| Number that could not read at all | 104 | |

| Number that could read a few syllables | 53 | |

| umber that could read imperfectly | 192 | |

| Total imperfectly-educated | 349 | |

| Number that could read tolerably, but most of whom had learned in prison or revived what they had learned in youth | 315 | |

| Moderately-educated | None | |

| Total | 664 | |

"Hence it appears," adds the chaplain , "that among 664 prisoners admitted into this prison, there is not one who has received even a moderate amount of education. Among the same number of male prisoners, judging by my past experience, I feel persuaded that there would be many who had received a fair amount of education. This confirms me in the opinion which I expressed last year, 'that the beneficial effects of education are more apparent among females than men.'

"Of the same 664 prisoners, the minister tells us—

| 453 | trace their ruin to drunkenness or bad company, or both united. |

| 97 | ran away from home, or from service. |

| 84 | assigned various causes of their fall. |

| 6 | appear to have been suddenly tempted into crime. |

| 8 | state that they were in want. |

| 16 | say they are innocent. |

| 664 |

Brixton Female Convict Prison, chapel, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

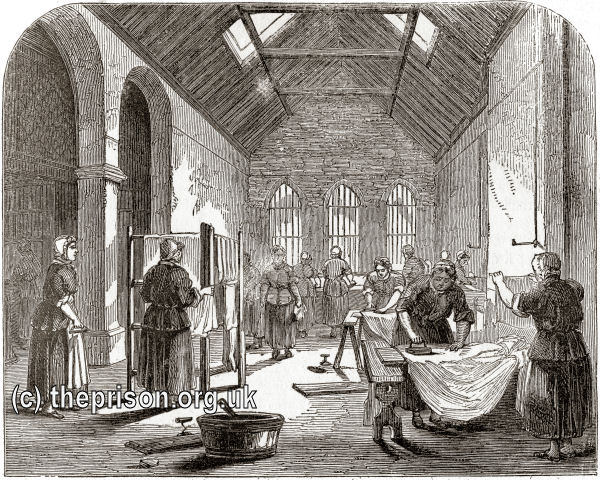

Brixton Female Convict Prison, laundry, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

Brixton Female Convict Prison, nursery, 1862. © Peter Higginbotham

In 1869, the female inmates were relocated to the new purpose-built female prison at Woking, with Brixton re-opening the following year to house male convicts.

Between 1882 and 1898, Brixton was used as a military prison. The regime was substantially the same as those of all civil prisons. The majority of the prisoners were employed in oakum-picking and shot drill. Others were employed in various works about the prison, and in tailoring and repairing shoes. The prisoners who were employed their cells were there at all times, except during chapel, exercise, or shot drill.

With the closure of Newgate prison in 1901, Brixton was converted for use as the Brixton Remand Prison, also known as the House of Detention, serving the whole of London, with executions also taking place there.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- London Metropolitan Archives, 40 Northampton Road, London EC1R OHB.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Has a wide variety of crime and prison records going back to the 1770s, including calendars of prisoners, prison registers and criminal registers.

- Find My Past has digitized many of the National Archives' prison records, including prisoner-of-war records, plus a variety of local records including Manchester, York and Plymouth. More information.

- Prison-related records on

Ancestry UK

include Prison Commission Records, 1770-1951

, and local records from London, Swansea, Gloucesterhire and West Yorkshire. More information.

- The Genealogist also has a number of National Archives' prison records. More information.

Census

Bibliography

- Impey, Christopher House on the Hill, Brixton: London's Oldest Prison (Tangerine Press, 2019)

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.