County Gaol and Bridewell / HMP Maidstone, Maidstone, Kent

In 1806, planning began for a new County Gaol and Bridewell, or House of Correction to replace the existing gaol and its neighbouring bridewell on East Lane (now King Street). In 1811, a site for the new prison was purchased on County Road, Maidstone. The buildings, designed by Daniel Asher Alexander, were initially intended to house up to 450 inmates, each with their own sleeping cell. In 1811, the cost of the scheme was estimated to be in the region of the then massive figure of £160,000, making it second only to London's Millbank Prison in its expense. To make this viable, construction was spread over twelve years. However, when the work was completed in 1823, the final cost was over £215,000.

County Gaol and House of Correction, Maidstone, 19C.

The prison received its first inmates on 8 March 1819, when 141 debtors and felons were transferred from the King Street prison, with the bridewell inmates following in November of that year.

At the centre of the new buildings was circular four-storey tower. Its lower two storeys contained offices and the keeper's quarters, while the chapel occupied the top two storeys. To the north, east and south were cruciform complexes of cell blocks with a turnkey's tower at the centre of each cross. Each block was physically separate from all others though they were linked at the first- and second-floor levels by iron walkways. Each wing was divided along its length by a wall, so allowing two classes of inmate to share a floor. The ground floors were mostly open arcades with some dayrooms and workrooms. The design of the prison allowed a particularly large scheme of inmate classification. In the 1820s, thirty categories of male prisoner were designated and eight of female.

An early account of the new prison in October 1819 reported:

This immense prison, covering a greater space than probably any other in the kingdom, stands in an any situation close to the town; it is calculated, including the House of Correction, for 450 prisoners, each having a separate night cell: at this time the number is 270. Since it has been in habited, there has not yet been more than 420 at any one time. There are in all 27 classes, each having a distinct yard and ward, and no communication whatever with one another; the yards are large, airy, and very dry, the ground being covered with broken shells instead of gravel.

Each yard has a covered colonnade adjoining the day-room, for the prisoners to walk in wet weather.

Irons are only used for felons previously to trial, and misdemeanants of the worst description; and the gaoler said he intended to get rid of them entirely soon: they are evidently unnecessary, the prison being perfectly secure.

There were at this time only three children under 17 years of age, of which one was a girl of 10 years, waiting to be tried, together with her brother of only 7 and a half, for stealing a pair of shoes. Mr. Powell, the gaoler, said that, contrary to experience in most other instances, here, the number of juvenile prisoners did not increase; he thought they rather decreased, The prison appeared throughout remarkably clean; it is white-washed twice a year, prisoners being employed for that purpose. The night cells are sufficiently large, all glazed; cast iron bedsteads,of a very good description, are universal; the allowance of bed-clothes is two blankets and a rug, the bed consists of a coarse bag half filled with straw, the bedding is hung up by each prisoner every morning, in the passage, on nails fixed in the walls, that it may get a thorough airing be fore it is again used; these passages are heated in winter by flues, the warmth passing into the cells by means of holes over the doors.

The appearance of the prisoners was in general healthy: there were 13 at this time in the infirmary, one only with fever.

The infirmary is a separate building,and well calculated for the purpose.

No instruction is at present given to the prisoners, but it is in contemplation to establish a school for the boys: books are distributed at the direction of the Chaplain, who has a house adjoining the prison; he visits the gaol about three times a week: service is performed on Sunday, and prayers are read on Wednesday and Friday.

The chapel is at the top of one of the circular buildings, occupied by turnkeys. The classes have each a separate pew, with a division sufficiently high to prevent one seeing another, but they are all looked into from the centre.

It is remarkable that the Chaplain's house has windows to wards the street only, there being none on the prison-side, though, if there were, he would be able to look into several of the yards.

There are three turnkeys' lodges, besides the gaoler's house, all having inspection into a certain number of the yards, which are thus all overlooked.

Employment. There were employed at this time at a windlass, to raise water for the supply of the gaol, 24, chiefly vagrants, (in two gangs of 12 each,) 12 in the garden, and about 50 in hand-spinning, making twine, and weaving sacking, be sides ten or twelve in white-washing. Two manufactories are building; when these are finished, Mr. Powell told me a much greater number could be occupied, and that a turnkey would attend constantly in each, to watch the prisoners and preserve order. The women are employed in needlework and washing, but I saw none of them appear really busy. Prisoners for trial and debtors have no occupation, which is confined to those sentenced to hard labour.

Clothing. The convicts have a prison-dress, consisting of a flannel waistcoat,with a coarse linen one over it, and coarse linen trowsers, many complained to me of wanting shoes.

Food. The following is the diet table for prisoners engaged in labour.

| Sunday | 1 lb. bread | ½lb. beef | 1 lb. potatoes |

| Monday | do. | 1 pint ox-head soup | do. |

| Tuesday | do. | ½lb. oatmeal | 2 lbs. do. |

| Wednesday | do. | ½lb. meat | 1 lb. do. |

| Thursday | do. | ½lb. oatmeal | 2 lbs. do. |

| Friday | do. | 1 pint soup | |

| Saturday | do. | 1 lb. suet pudding | do. |

For those not engaged in labour.

| Sunday | 1 lb. bread | ½lb. beef | 1 lb. potatoes |

| Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, 1½ lb. bread | |||

| Wednesday | 1 lb. bread | 1 pint soup | |

Adjoining to each day-room is a sink, and water let in for the prisoners to wash: in cases of their neglecting to do so every morning, they are deprived of part of their daily allowance.

There is no inspection into the day-rooms, except through iron-bars at the entrance when the door is left open; what is passing in these, as well as in the manufactories, can only be seen by entering them.

The yards, besides being overlooked from the governor's and turnkeys lodges, have small holes cut in the surrounding walls, so that persons passing through the passages can see into them. No punishment is used except solitary confinement.

The gaoler said the prisoners were in general very orderly, and well behaved, and so they appeared to be; there was very little noise and no gaming observable.

The actual classification is as follows.

| Common Gaol. | |

| No 1. | Prisoners for trial for capital felonies. |

| 2. | Do. for felonies. |

| 3. | Do. for misdemeanours. |

| 4. | Males convicted of misdemeanours. |

| 5. | Do. convicted of capital offences. |

| 6. | Females do. |

| 7. | Juveniles for trial. |

| 10. | Females convicted of misdemeanours. |

| 11. | Do. for trial. |

| 12. | Deserters. |

| 13. | King's evidence. |

| 14. | Now used for soldiers, convicted by Courts Martial, but intended for males accused of beastly crimes. |

| Debtors. | |

| 16. | Common debtors. |

| 17. | Do. |

| 18. | Master debtors. |

| 19. | Do. |

| Penitentiary. | |

| 21. | Penitentiary, Males 1st .class. |

| 22. | Do. 2d. |

| 27. | Do. 3d. |

| 24. | Do. Females. |

| House of Correction. | |

| 20. | Servants in husbandry, &c. short terms. |

| 25. | Apprentices, juveniles, &c. do. |

| 36. | House of Correction, women. |

In 1837, the Inspectors of Prisons gave a lengthy report on the establishment:

1. Site, Construction, &c.

This prison stands on an elevated situation to the north of the town of Maidstone, and covers no Jess than fourteen acres of ground. It was built at a cost to the county of about 200,000l., and was first occupied in 1819, since which a separate prison for females has been erected within the south-east angle. The material of its construction is the Kentish rag-stone, dug near the spot. It is a massive and substantial building, and has hitherto required little external repair. The Courts in which the assizes and sessions are held stand in front of the prison, and there is a door opening from the back of the court-house into the prison-garden, through which prisoners are taken directly to trial without quitting the prison walls. Some few escapes have been attempted, which will be noticed under another head, as they do not appear to have been attributable to want of security in the prison. The sessions-house and the chaplain's residence are the only buildings adjoining the prison, and a carriage road surrounds and separates it from the neighbouring houses. These are mostly small, but the upper windows of several of them overlook the prison, and a lime-kiln overlooks three of the wards, (Nos. 8, 9, and 10,) the top of which has, in several instances, been used by confederates as a place of communication with prisoners, and for supplying them with tobacco. Nearly the whole of the buildings are fire-proof, with the exception of the chapel. They are not insured. The prison comprises no less than 27 wards for male, and 7 wards for female prisoners, with 39 day-rooms, airing-grounds, and covered colonnades for exercise in wet weather. The common gaol for males contains 17 wards; three of the largest wards have two day-rooms each, the others one day-room each, and to every ward there is a spacious yard. The house of correction for males consists of 12 wards, each having a day-room and airing-yard. There is a large workhouse used as a manufactory, and also a mill-house and tread-mill, divided into eight compartments. The common gaol for females consists of four, and the house of correction for females of three wards, with a day-room and airing-yard to each. The several wards are at present applied to the following purposes, viz.—

No. 1. Used either for prisoners committed for trial at the sessions, or for convicts under sentence of transportation; contains 29 arched sleeping-cells, 8 feet 8 inches long, by 7 feet 1 inch wide; height of cells to crown of the arch, in upper tier, 9 feet 1 inch; in lower tier, 9 feet 7 inches. One double cell.

No 2, Misdemeanants for trial. Twenty-nine cells, in two tiers, of same dimensions as those in No. 1. One double cell.

No. 3. Prisoners for trial at assizes. Thirty-nine cells, in two tiers, of same dimensions as those in No. 1. One double cell.

No. 4. Divided into two parts, A and B. Military prisoners, deserters, and casual misdemeanants committed to the gaol. Thirty-nine cells, in two tiers, of same dimensions as those in No. 1. One double cell.

No. 5. Six condemned cells, for prisoners under capital sentences. No. 6. Nineteen condemned cells, for the same. Neither of these wards occupied at the time of inspection.

No. 7. Juvenile offenders for trial. Twelve sleeping-cells, 8 feet 8 inches long, by 7 feet 1 inch wide. Height of cells, both tiers, 9 feet 6 inches.

No. 8. Vagrants. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 9. Vagrants. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 10. Poachers. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 11. Poachers. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 12. Re-committed prisoners for trial for felony. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 13. King's evidences. Ten cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 14. Prisoners sentenced to solitary confinement. Ten cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 15. Smugglers maintaining themselves. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 16 to 19. Debtors. Two classes of cells, viz., single cells, 9 feet 3 inches long, by 8 feet 6 inches wide, and 8 feet 6 inches high and double cells for three each, 18 feet 5 inches long, by 8 feet 5 inches wide, and 9 feet 4 inches high.

No. 20. Summary convictions. Twenty-seven cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7. One double cell. A well and engine-house for raising water.

No. 21. Misdemeanants convicted at assizes and sessions. Twenty-seven cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7. One double cell.

No. 22. Juvenile convicted felons. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 23. Convicted felons. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7.

No. 24. Convicted felons. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7. Tread-wheel.

No. 25. Convicted felons. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7. Tread-wheel.

No. 26. Convicted misdemeanants. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7. Communicates with the manufactory.

No. 27. Convicted felons. Twelve cells, of same dimensions as those in No. 7. Communicates with the manufactory.

The seven wards in the female prison contain 38 sleeping-cells, of which 18 are single cells, one is for two, 11 for three, and eight for four prisoners, thus furnishing room for 85, besides the laundry, wash-house, and matron and officers' departments.

The prison has the means of accommodating 453 prisoners with separate sleeping-cells, the dimensions of which are, for the most part, 8 feet 8 inches long, by 7 feet 1 inch wide, and 9 feet 6 inches high, being more than are likely to be required under ordinary circumstances; the greatest number in confinement, at one time, during the last two years, having been 415; although at one period, in the year 1834, the total number in custody reached 533. The male prisoners, therefore, except some of the debtors, usually sleep in separate cells.

The means of inspection are deficient. The windows of the keeper's and turnkeys' houses have a view over some of the airing-yards, and the bridges or passages leading to the chapel have also a view over the yards, which can likewise be looked into from the passages without, through certain small apertures made in the walls for that purpose; but the colonnades can only be partially observed; and the day-rooms can only be inspected by leaving the outer doors of the wards open, in order that the officers may catch a glimpse of the day-rooms through the bars of the inner iron gate; but as the prisoners have generally the wit to retire into that part of the day-room which cannot be seen through the door-way, it is obvious that such a power of inspection as this must be quite worthless. The sleeping-cells can only be inspected by going to them.

The ventilation of the cells is badly contrived; as although there are pipes for the admission of air from the passages, yet the windows in general do not open, but are composed of small panes of glass, two or more of which are left vacant to receive air, and which, notwithstanding the shutter, will admit a considerable draft of cold wind. A ventilator placed in the window, or even a window which would open and shut, would be a desirable substitute for this clumsy expedient. In the debtors' wards the windows are in a very bad state. The prisoners break them to admit air in warm weather, and they are not repaired lest they should be broken again; which is an additional reason for adopting a different kind of window. The cells used for punishment in the female prison are not sufficiently ventilated. One of them, in which a woman was confined at the time of our visit, smelled closer and stronger than it could possibly have done with a proper supply of air. The temperature of the cells gives us no reason to suspect their being too cold for health, although some of the prisoners complained of cold during the late severe weather. On 11th January, at about six P.M., during a hard frost, the thermometer in several of the cells ranged from 42 degrees to 46 degrees, the upper tiers of cells being colder than the lower. Complaints were made to us by prisoners of their cells and bedding being damp, which seems to have arisen not from any defect in the buildings, but from the admission of damp air during the day, and from the exposure of the bedding also during the day to a current of damp air in the passage, where it is aired.

The prison stands on a dry soil, and no part of the buildings appears affected by damp. The drainage is good, by a common sewer to the river Medway. There are wells of 30 feet deep within the walls, which afford a supply of pure water. The whole of the prison is lime-washed every spring, and is' now neat and clean.

There is ample space for alterations or new erections within the present boundary-wall. This prison would afford an opportunity for introducing a system of separate confinement, at a moderate expense, for the untried, by throwing down the partitions between the sleeping cells in some of the wards, and making two cells into one, so as to form rooms 14 feet 2 inches long, by 8 feet 8 inches wide. The thickness of the partition walls between the cells, (about 14 inches,) is not indeed such, at present, as to prevent communication; but as there is only a single row of cells in each passage, it would be easy to alter the cells experimentally in any given ward, with a view to the individual separation of any class of prisoners whom it might be determined so to confine. An excess of from 40 to 50 sleeping cells beyond the greatest number requisite for two years past, besides 39 day-rooms convertible into two cells each, and ample building-ground, offer the means of commencing a system of individual separation in this prison, such as few others are likely to afford at so little cost. We submit whether the magistrates might not be required to provide a sufficient number of cells of proper dimensions for the individual separation of the untried?

2. Discipline.

The system of discipline is that of association in classes by day, and separation by night, with the exception of some of the debtors and female prisoners, who sleep respectively in separate beds in the same room. The spaciousness of the prison enables the classification of the Gaol Act to be carried into effect, and there are several subdivisions beyond what the law requires. For instance, in the gaol, prisoners for trial for capital felonies, for felonies not capital, re-committals for felony, and juvenile offenders, are placed in separate wards; in the house of correction, prisoners convicted of felony are divided into several classes, according to the length of their respective periods of confinement, and juvenile convicts are also kept in a distinct ward. If classification according to the technical description of the offence were of any value, such subdivisions would be improvements: but regarding the classification of the Act as wholly worthless, we can only consider the further subdivisions as equally delusive. It is quite a mistake to suppose a man committing a capital felony more immoral, on that account, than he who commits a felony not capital. If it were so, the offence of stealing in a dwelling-house implied, more depravity in 1833 than in 1834, when it ceased to be capital. It is idle to suppose that the removal of a few re-committed prisoners from the rest can prevent the bad effects arising from a system of association. Nor can the corruption of boys be prevented by classifying them in A juvenile ward together, for this plain reason, that they corrupt each other. We could not find that any practical good had resulted from this extended classification.

The untried associate at all times of the day, in their respective yards and day-rooms. The convicted also pass the day in association, at washing in the yard, at meals in the day room, during labour on the tread-wheel, or in the manufactory, during chapel, whilst under instruction, and in fact at all times, except when locked up for the night, or when in solitary cells for punishment. We did not understand it to be in the contemplation of the visiting justices to propose the abolition of the day-rooms. The prisoners have the means of speaking to each other, whilst in their sleeping-cells, from window to window; and a loud voice can be heard through the partition walls. The precautions against talking at night consist in a watchman who goes round outside, and in the wardsman within, whose duty it is to report any noise he may hear. Talking by night is, however, seldom detected, and is probably not much the practice, as the prisoners have opportunities enough of talking by day.

We were informed that silence was the rule of the prison; but there is no written or printed rule or order on the subject. It is, in fact, so little enforced, that no one would suppose there was any existing rule of the kind. Its enforcement in the day-rooms, at meals, washing, &c., depends entirely upon the wardsman, himself a prisoner, having other duties, such as sweeping and washing the day-rooms and cells, and bringing the food from the cooking-house, which puts it out of his power to be constantly with the others. But when the wardsman is present, the observance of silence is a mere farce. The wardsmen do not report for ordinary conversation short of a great noise or disturbance. From the statements of the prisoners, they do not seem to have the least difficulty in talking as much as they please with those in the same ward, provided they are not riotous. In chapel, where they are placed according to classes, they have the same facility, particularly as the chapel is so badly constructed that the prisoners in the gallery cannot all be seen either by the chaplain or officers. Even in the condemned cells they would seem to have the opportunity of intercourse; for the chaplain, in the month of March 1836, overheard two prisoners in these cells shouting to each other, and using low and profane language in reference to their trials. Prisoners on the tread-wheel, although under the frequent eye of the turnkey, besides a monitor, who is a prisoner, manage to talk in whispers, but have more chance of being reported and punished. The number of punishments inflicted by the keeper for talking whilst on the tread-wheel, in the year ending Michaelmas 1836, was 89; of whom 21 were confined in a dark cell for three days, 44 for two days, and 24 for one day; but it does not appear that any prisoners have been punished for the mere act of talking at other times; the inference from which agrees with the statements of the prisoners, viz., that they are allowed to talk in a quiet way when not upon the wheel. Whatever benefits, therefore, may be supposed to result from silence rigidly enforced, they have not yet been attained in this prison.

The position of the female prison separates it effectually from the male yards. Attempts at communication between male and female prisoners are, we believe, rare; but an instance lately occurred of a letter being thrown from the male into the female tread-wheel yard, which was suspected to have been done by a wardsman who had seen the female from the window of one of the cells in the upper tier of his ward. The fact could not, however, be fixed on him with certainty. As affording the means of communication, it should be noticed that the window of the kitchen of the male infirmary looks into the yard of the female infirmary, which, though a blind is used, ought to be stopped up, as instances of intercourse through it have occurred. The wooden partitions, also, between the male and female seats in the chapel, are so thin that holes have been cut and notes passed through them. It should also be remarked, that the head-turnkey, who is the husband of the matron, sleeps in the matron's apartments in the female prison, which are contiguous to the sleeping-cells of the women. The turnkey referred to bears an excellent character; but it is easy to imagine the abuses to which such a practice might lead; and we submit that it is contrary to the spirit if not to the letter, of the present Gaol Act.

The only kind of hard labour is the tread-wheel, which is divided into eight separate compartments, and will hold 92 persons at once. During the month of inspection (January) the number of working-hours at the wheel is 6¼, and the number of feet of daily ascent By each labourer, 12,000; being about one-third less than in the summer months, when the working-hours are 9½, and the feet of ascent 18,240; so that a man sentenced to two or three months' hard labour in the summer season undergoes one-third more of the tread-wheel than he who is sentenced to the same period in the winter, and that without any difference of diet. This inconsistency is accompanied by another evil, viz., the length of time which the prisoners pass in bed in the winter months, being upwards of 15 hours, when the days are at the shortest—a space of time far too long for the prisoner's welfare either mental or bodily. These inconveniences, however, appear to be inseparable from any system of association, except in so far as that the diet might be better proportioned to the labour than it is at present. The work of the tread-wheel is disliked in itself, but on account of the superiority of the diet of prisoners at hard labour over that of others who do not work, the former generally consider their situation preferable. On a late occasion, when, to make room for an unusual number of male convicts, the females were taken off the wheel, the latter complained that they were not fairly used, as by not working on the wheel they lost the better diet which they had whilst they were on it. Those prisoners who are unfit for the wheel are employed in the manufactory in making sacking, matting, and shoes. The manufactory, although an orderly establishment, does not preclude conversation; and the liveliness attendant upon a work-room renders it anything but a place calculated for punishment. Able-bodied female prisoners are put to the wheel; but the majority of them are employed in washing, ironing, mending, &c. The tread-mill is let for grinding flour; but the gross profits of every kind of productive labour done in the prison, including the rent of the mill, do not exceed 320l. per annum, and after deducting the miller's and superintendent's wages, and expenses of repairs, &c., the balance in favour of the county is a mere trifle. The manufactory undoubtedly furnishes the means of labour for prisoners unfit for the wheel, but it has nothing in it of a penal character. Such labour, in society, with facility of conversation, is of course quite a different thing from what it would be in the solitude of the separate cell. The association prevents the labour being penal, or, in other words, renders it wholly useless as an instrument in deterring from crime.

The prison has visiting-rooms for the reception of the prisoners' friends. The visiting-room is divided into three compartments with gratings between them. In one of these the visitor stands, and in the other the prisoner—the intermediate compartment being left vacant. The turnkey might occupy it, if necessary; but it is considered sufficient for him to stand just outside the door, so that he can hear the conversation. Prisoners before trial are allowed to receive visits daily, between the hours of 12 and 2, and at other times, under special circumstances. Debtors' visitors are allowed daily, from 10 till 4 o'clock, the same visitor not being permitted to come twice the same day. Convicted prisoners are only allowed to see visitors by a written order of a visiting justice, which it is not the practice to grant until four months after conviction, and a similar period intervenes before another visit. Prisoners under summary conviction only receive visits by justices' orders. The reparation and gratings of the visiting-rooms prevent the possibility of a visitor giving any thing to a prisoner whilst in that situation. No particular proof of relationship is required; it is left to the officer's discretion to refuse admittance to improper persons. Letters are permitted to be received and sent by convicted prisoners as well as others, subject to the inspection of the keeper in cases where he suspects they relate to any crime against the law, or offence against the discipline of the prison. We submit, that convicted prisoners ought not to be allowed this privilege at least until they have been a definite time in prison, except under very special circumstances.

Money is taken away from all prisoners on the criminal side on their entrance into the prison, and the amount is entered in a book, that it may be returned on their discharge. Prisoners maintaining themselves have their money given them by small instalments for that purpose.

The use of tobacco is prohibited; but there can be little doubt that it is habitually introduced. Some prisoners contrive to conceal it about their persons, notwithstanding their being searched on admittance; others have it secreted in the provisions which they are allowed to receive. J. J., a convicted felon in ward No. 24, informed us, that once another prisoner assaulted and pulled him down from off the wheel, because he (J. J.) had drawn some tobacco out of the other prisoner's trousers.

The prisoners on the criminal side have access to the publications and religious books authorized by the chaplain. The debtors take in newspapers, without restriction, and are little, if at all, restrained as to books, magazines, or other publications.

We discovered in the day-room of the debtors receiving the gaol allowance a number of small square stones in the form of dice, but not marked. They were evidently intended to be used as dice. The debtors can have little difficulty in obtaining either cards or dice, when they wish it, and dice have been observed in their rooms by the chaplain. The prisoners in the criminal wards occasionally cut holes in the wooden benches of the day-rooms, in order to play some games with pegs. This is one of the results of day room association.

The employment of prisoners as wardsmen, and in menial offices in the prison, prevails here, and is regarded as an inconvenience. The wardsmen are mostly selected from those convicted prisoners who are disabled by infirmity from working at the tread-wheel, and also as a reward for good behaviour. The keeper and turnkeys agreed, however, that the duties of wardsmen would be much more efficiently performed by officers who were not prisoners. All the opinions which we could collect, concur, indeed, that the wardsmen are not to be depended upon; sometimes they secrete improper articles themselves; and it is seldom that they exercise a proper control over the other prisoners. The situation of a wardsman is generally desired, as it confers the advantage of some addition to the diet, besides exemption from tread-wheel labour. The impropriety of allowing such indulgences to any prisoner whatever, however good his conduct during confinement, can admit of no question: it is quite inconsistent with the object for which punishment is indicted. Undoubtedly, the discontinuance of prisoners as wardsmen would occasion the necessity of having additional officers to perform their duties; but it should be remembered, that in such duties as cleaning the wards, bringing the meals, &c., no economy is justifiable which interferes with the paramount object of rendering a prison a place of punishment. A practice prevailed of the wardsmen selling writing-paper to prisoners, which was stopped by the magistrates; and we have not been able to ascertain that any of the wardsmen now derive profit from any articles sold or let to prisoners. Some of the wardsmen shave the other prisoners, and are paid for it by the county, not by the prisoners. The matron and female turnkey declared they had no confidence in the character of the wardswomen, who did not keep any thing like silence; nor could they do so, if disposed, as they had often occasion to leave the prisoners.

A number of prisoners are employed in casual services about the prison, such as whitewashing, gardening, &c., which are considered labour for punishment. Exclusive of these, the number of prisoners in regular employment as wardsmen, or in menial services, on the 10th February last, was, males 28, females 13, total 41. On that day. the total number in custody was, males 267, females 38, total 305; being a proportion of about 13 per cent. The whole of these employments were under the sanction of the visiting justices.

A practice prevails of removing female prisoners from this prison to St. Augustine's, Canterbury, after their conviction; it being customary for the Courts at Maidstone, upon application previously made by the visiting justices of St. Augustine's, to sentence to that prison such female convicts as may be wanted for workwoman, as it frequently happens that there are not female prisoners enough in St. Augustine's to do the prison work. Six women were so removed in the course of the year 1836. The employment of convicted prisoners in any services which do not fall within the description of penal labour, is open to strong objection: magistrates are too prone to view the matter as merely one of economy. Occupations of this kind are sometimes not only improper, but inconsistent with the safe custody of the prisoner. As an instance of this, E. B., a female convict, under sentence of transportation in this gaol, not long since was employed, as nurse, to sit up with a sick prisoner in the female-infirmary. In the morning she found means of going to the wardrobe where the clothes used by prisoners before their admission were kept, and changed her prison-dress for ordinary clothing; she then walked coolly to the prison-gate, and deceived the turnkey by telling him that she was no prisoner, but came from the town to sit up with the sick woman. Upon this the turnkey let her out, and she was not retaken till she had proceeded 2½, miles from the prison, on the Chatham road.

3. Religious and other Instruction.

The Rev. John Winter has been 15 years chaplain of this prison. He is 48 years of age. Divine service is performed by this officer twice on Sundays; and prayers are read by him, every morning at h past 8; the whole Morning Prayer, according to the Rubric, being read on Wednesday and Friday, and prayers selected from the Liturgy on other days. He administers the Holy Communion, from time to time, to such prisoners as he thinks in a proper frame of mind to receive it; and attends especially upon prisoners under sentence of death. His salary is 250l. per annum; he has no other preferment, and resides in a house belonging to and adjoining the boundary-wall of the prison; but which has no communication with it, otherwise than by the common prison-gate. A door between the back of the chaplain's house and the prison would be a convenience; but the magistrates consider that such an alteration would be insecure. The chaplain is always accessible, and attends at night, or any other time, if sent for. He visits the prisoners in solitary confinement three times a week, and those in the dark cells daily. He sometimes talks to prisoners in the day-rooms; but from the numbers congregated there, he finds that he can do little good in that way. He superintends the schoolmaster, and himself instructs the female prisoners. The conduct of the prisoners during chapel is in general orderly; but the building is so badly constructed, that neither the chaplain nor officers can see all the prisoners in the gallery. There is no calling over the names of the prisoners before chapel; the wardsman is responsible for the attendance of the prisoners of his ward. It rarely happens that any one absents himself: but not long since, a prisoner contrived, whilst on his way to chapel, to return to his cell, and, during the service, to get over the wall of his yard, into the part near the boundary-wall; over which he would probably have escaped, if a turnkey had not seen him from one of the chapel-bridges. The keeper regularly attends chapel; but there are four of the turnkeys, including the two at the gate, who do not constantly attend; their services being required in other parts of the prison. The superintendent of the manufactory and the miller, both of whom are officers of the establishment, are not in the habit of attending, even on Sundays. These two officers, we were informed, stipulated, on their appointments, that they should not be required to attend chapel. The debtors are not obliged to come to chapel, but some of them make their appearance on Sundays. Prisoners confined in the dark cells are not allowed to attend, but those in the solitary cells attend daily. The thinness of the wooden partitions in the chapel is stated, both by the chaplain and officers, to afford easy means of communication, and the prisoners are so situated that they can make holes through them without being seen; so as to frustrate the object of classification, worthless as it is. The different classes have separate passages from their wards into their seats in the chapel; but those of the same class have ready means of intercourse whilst going to, attending at, or returning from, chapel. The chaplain lectures in the infirmary every Sunday and on alternate week-days.

A schoolmaster (not a prisoner) is regularly employed, at the very moderate salary of 12s. per week, who instructs daily in reading, m distinct classes, the prisoners committed for trial, and the juvenile offenders. The number receiving instruction was, on 4th January, 60, and on the 11th January, 25, the variation being caused by the intervention of the sessions. On Sundays he instructs such of the convicted prisoners as, being sentenced to labour, cannot attend him during the week. His present number of Sunday pupils is 46. There is no school-room; consequently, the master is obliged to teach in the day-rooms, which is attended with several inconveniences. The chaplain instructs the female prisoners in their laundry every Wednesday and Friday, and says he finds them improve more than the men. Writing is not taught in the prison.

All books in use among the prisoners are selected by the chaplain, and are purchased from the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge.

Although the acquirement of instruction is left optional with the prisoners, yet there rarely appears any reluctance to attend it; and some of them, particularly the young, make fair progress in learning to read in the course of two or three months. To juvenile offenders instruction has the additional attraction of relieving them, for a short time, from the wheel—an indulgence of which few, perhaps, under the circumstances, will be disposed to disapprove. But, after all, the stock of knowledge that can be obtained in such short periods of confinement as three months and under, must be very small; and when the bad effects of association are taken into account, it is to be feared that the instances of moral and religious improvement are extremely rare. It is the chaplain's opinion that prisoners confined for short periods derive scarcely any benefit from instruction of any kind. Indeed,, the best way to impart religious instruction with effect is by private converse with the prisoner; which is impossible, under a system of association; and the labours of the chaplain must therefore be chiefly confined to divine service and to the furnishing of religious books, which the prisoner, if he has time, has seldom the ability or inclination to peruse with advantage. The chaplain, who appears to perform his duties with zeal and fidelity, is decidedly of opinion that no system but that of the cellular separation of prisoner from prisoner, can afford any well-grounded hope of effecting their moral and religious improvement.

4. Health.

The surgeon, who has a large private practice in the neighbourhood, has a salary of 200l. for his services in the prison, including medicines. He does not appear to attend constantly himself, and had not signed the attendance-book from the 13th November to the 11th January; but his assistant, who is also a regular surgeon, attends daily. The circumstance of the surgeon not performing the whole of his duties in person is irregular and improper. All the wards in which any sickness is reported are visited daily, as well as the infirmary, and patients are attended by night as well as by day. Prisoners under punishment in solitary cells are not visited, unless reported sick; the reason assigned for this is, that prisoners are always ready to complain if anything is the matter with them, and the turnkeys to report it, that there is little fear of their falling ill without its being known. One important duty of the surgeon is not performed, viz., that of examining every prisoner on admission, before he is passed into his ward. The prisoner is washed in a bath on his admission; but is allowed to enter the ward and mix with other prisoners before the surgeon has examined him—a practice too common in prisons, but contrary to the Gaol Act, and which might be the means of introducing an infectious disease. The surgeon, however, examines every prisoner before he is placed upon the tread-wheel.

The sick in the male and female infirmaries are attended by a prisoner of each sex respectively. An instance has been mentioned of a prisoner escaping from the male infirmary during divine service—a circumstance which indicates no great vigilance on the part of the infirmary wardsmen, who are, of course, no better than others of their class. Silence is not required to be observed in the infirmaries, and the surgeon considers that it might have a prejudicial effect upon the recovery of invalids. It is impossible to enforce such rules in an infirmary. The treatment of sick prisoners in separate cells is the only method of avoiding the abuses which at present attend prison infirmaries.

The diseases appear to have been in general of an ordinary kind, such as diarrhoea, bilious affections, disordered lungs, &c. No connection can be traced between these complaints and the locality of the prison, which is believed to be very healthy. At the period of our visit (January, 1837,) only seven male and eight female patients were in the infirmary, whilst great sickness prevailed in the workhouse, the barracks, and generally in the town of Maidstone. The proportion of cases of slight indisposition in the year ending Michaelmas, 1836, was about 25 per cent, upon the whole number confined in the year; that of infirmary cases only 8.52 per cent.; and that of deaths only 0.32 per cent., or seven in the whole year. The diet is supposed by the surgeon to produce a tendency to diarrhoea. The tread-wheel has the effect of reducing the prisoners in bulk, and few can endure it for long periods, such as twelve months, with the ordinary prison diet, without injury to their constitutions.

By the dietary table it appears that a man employed at hard labour receives weekly 174½ ounces of solid food, 13 pints of gruel, and 4 pints of soup made of ox-heads, peas, &c., of good quality. Prisoners for trial receive 168 ounces of oread and 7 pints of vegetable soup in the course of the week. Misdemeanants not sentenced to hard labour the same, and two pints of gruel a day when employed. Poor debtors the same, with the addition of one pound of potatoes daily. The dietary table is affixed in the cooking-house and turnkeys' house, but not in any place accessible to the prisoners. Scales and weights are provided, but are rarely asked for by the prisoners.

The prisoners allowed to find themselves in food, bedding, and clothing, are debtors, prisoners for trial, and convicted prisoners not sentenced to hard labour. Debtors not receiving gaol allowance are permitted to purchase eatables, with no particular restriction in quality or quality, except that they are not to lay in more than two days' supply at a time. In liquors they are limited to a pint of wine each day, or a quart of ale or strong beer. Other prisoners not receiving gaol allowance are on the same footing, except that prisoners before trial are not allowed wine, and convicts neither wine nor beer. The prisoners write their orders on a slate; a shopman comes and brings the provisions, and the turnkey takes them into the wards. The practice of allowing a convicted prisoner, under any circumstances, to find himself with provisions, notwithstanding the discretionary power vested in the justices by the 15th regulation of the Gaol Act, is extremely objectionable, particularly when the prisoners associate, and where it is not uncommon for those maintaining themselves to give a part of their provisions to others maintained by the county. The poorer prisoners do not appear to think it unfair for their richer associates to have their own eatables, but they complain of not being permitted to receive such occasional presents as their friends may be able to bring them; the rule being that prisoners must maintain themselves either entirely, or not at all.

The cost of clothing each prisoner is estimated at 15s. 6d. per head per annum. Some prisoners, however, clothe themselves. There is only one sort of prison dress, and it is not varied by seasons. It is a coarse woollen dress, which costs about 11s., and lasts upwards of a year. The shoes and shirts are the only articles of clothing made in the prison. The keeper goes into the wards every Sunday morning before chapel, and inspects the prisoners' clothing: it is not frequently destroyed, but, when it is, the offenders are punished by solitary confinement.

The cost of bedding is estimated at 18s. 3d. per head per annum; but some prisoners find their own. It is bought in the town, and is every morning taken out of the sleeping-cells, and aired in the passages, or in summer in the yards. We have already observed that at this season of the year, (the winter,) the bedding frequently becomes damp by the air in the passages, and that some different mode of ventilating the cells and passages would be an improvement. Private bedding is not taken out of the cells to be aired in the same way as that of the prison.

The prisoners' washing is not conducted with regularity, as we were informed by more than one prisoner that they now and then fall out about the use of the pail, and it is a time when the prisoners converse pretty freely together. The combs are in a bad state throughout the prison. The allowance of two combs to each ward is not sufficient, and it would be but an inconsiderable expense if every prisoner were allowed a comb to himself. The whole of the linen is washed in the prison by the female prisoners.

The personal cleanliness of the prisoners is as great as can be reasonably expected. The prison was generally clean at the time of this inspection, and the whole is lime-washed annually, as required by law. Chloride of lime is used for purifying the infirmary.

5. Prison Punishments.

The total number of punishments inflicted in the year ending Michaelmas, 1836, for offences within the prison, was 510, or about 23 per cent, on the whole number of prisoners. They appear to have consisted almost entirely of confinement in dark cells. Only one man was whipped in the year. The instrument of whipping is a cat-of-nine-tails made of cord. It is performed by a turnkey, in the presence of the keeper and surgeon, and two dozen is the number of strikes ordinarily inflicted. The number of punishments for breach of silence on the tread-wheel was 89, or 17 per cent. upon the whole number of Punishments; but we could not ascertain that any punishments had been inflicted for mere breach of silence at other times. The inference is, as we have before remarked, that the wardsmen scarcely ever report for mere conversation, and that prisoners are not habitually punished for talking, unless it is during labour at the wheel, or accompanied by noise or outrageous conduct. This is further confirmed by observing the very small number of punishments inflicted on the untried, being only 29 in the year, or about 6 per cent, on 434, being the number committed for trial in the year, exclusive of debtors. A discipline of silence, to make it of any value, should be enforced with the utmost rigour, and punishment should be inflicted with certainty for breach of it: the discipline of this prison is not, in this respect, what it professes to be.

The keeper remembers only one instance of an unnatural offence attempted within this prison, which was 14 years since. The parties were tried for it by the ordinary course of law, and acquitted.

The punishment of locking-up in a dark cell, with reduced diet, is undoubtedly dreaded; and the imprisonment in solitary cells, pursuant to sentences of courts, is regarded as a severe punishment. R. B., a military prisoner, who had been nearly two months in solitary confinement, under sentence of a court-martial, told us that he thought his punishment much worse than the tread-wheel. The solitude of such prisoners is, however, broken by removal to a different sleeping-cell at night; where they, no doubt, find opportunities of communicating with prisoners in the adjoining cells.

6. Officers.

The keeper, Mr. Thomas Agar, has filled that office above 15 years. He is 63 years of age, and is a lieutenant in the army. He gives security to the sheriff in the penalty of 5,000l. He visits the prisoners in their wards daily, or as often as practicable in so large a prison. He is not in the habit of visiting at night after locking-up. He does not make it a constant rule to examine the bedding, locks, &c., himself, but receives reports of their state from the turnkeys. He receives the complaints of all prisoners, whether made through the turnkeys or to himself directly. He never absents himself from the prison, unless upon duty or by leave of the visiting justices. He superintends the several journals, character, and account-books, kept in the prisons.

All the turnkeys but one reside within the prison. Having perceived by the chaplain's journal that information had lately been given, by a discharged prisoner, in regard to beer and tobacco alleged to have been introduced a twelvemonth before, with the knowledge of one of the turnkeys and his wife, we thought it right to make some inquiries into the matter, and found that the visiting justices had dismissed the charge against the turnkey and his wife, it being unsupported by any evidence beyond that of the discharged prisoner, whom the justices deemed unworthy of credit. There is reason to believe that one of the prisoners, employed as a cook, found the means of obtaining beer twice in a soup-pail, whilst the turnkey in question was engaged at the sessions-house; but the justices did not think there was any ground for questioning the fidelity of the turnkey, and made no entry in their minute-book upon the subject.

We have already noticed the impropriety of the head turnkey sleeping in the female prison.

7. Miscellaneous.

The proportion of prisoners previously committed to this or other prisons was, upon the total number of prisoners committed, in the course of the year ending—

| Michaelmas 1835 | 18 per cent |

| " 1836 | 19 " |

It appears, that, out of 1,706 committals to the criminal side of this prison in the course of the year ending Michaelmas 1836, 192 were under the age of 17, and 452 between the ages of 17 and 21. Juvenile felons are kept in separate wards both before and after trial, and they are also separated from others on the tread-wheel and during instruction. The juvenile misdemeanants and minor offenders are not, however, in general separated. In, inquiring into the histories of many of these boys, we found them almost always the same. Brought up with scarcely any instruction, and imbued with no religious principles, their homes usually uncomfortable from disunion in the family, or from ill treatment; friendless outcasts upon the world, they have begun their career of crime on the first impulse of want, and continued it from inability to obtain employment. Their situation on being discharged from prison is truly pitiable, as they rarely know which way to turn, to obtain a livelihood. An instance occurred during our visit, of three boys who had been sentenced to three months' imprisonment for stealing two silk handkerchiefs, and were on the point of their discharge. Their conduct had been good whilst in prison, and one of them particularly had made great progress in instruction, and was, in the chaplain's opinion, a very promising lad. These boys were most anxious to go to sea, or anywhere to be actively employed, but did not know how to set about it, or to whom to apply. They would gladly have accepted an offer of emigration immediately upon their discharge, and might probably have turned out well. Such cases are so common, that it is impossible for private charity to render any effectual assistance, and any public provision that could be made for them on their discharge would be highly desirable.

The number of military prisoners committed to this prison in the year ending Michaelmas last has been very considerable, being 245. The county receives 6d. per head per diem for their subsistence, and they are maintained as other prisoners. The visiting justices consider them a great incumbrance, as they are usually a very troublesome class of offenders. They are kept in a separate ward.

The Commissioners of the Customs allow 4½. per diem for the maintenance of every smuggler committed to the gaol. It is paid at the gate by an officer of the Customs, and with it the prisoner maintains himself. For those offenders against the revenue laws who are sentenced to the house of correction and hard labour, the Board of Customs pays 1s. per head per diem, to the credit of the county, and they are then maintained by the county in the same way as other prisoners.

The number of prisoners in custody was—

| On the 11th January 1835 | 378 |

| " 1836 | 361 |

| " 1837 | 294 |

| l0th February 1837 | 305 |

A gradual diminution is here exhibited, which appears to be confirmed by a comparison of the numbers committed to the prison in the course of the three years ending Michaelmas 1836. The number committed was—

| In the year ending Michaelmas 1834 | 2,167 |

| " 1835 | 1,977 |

| " 1836 | 1,832 |

In 1878, following the nationalisation of the prison system, the establishment became Her Majesty's Prison Maidstone.

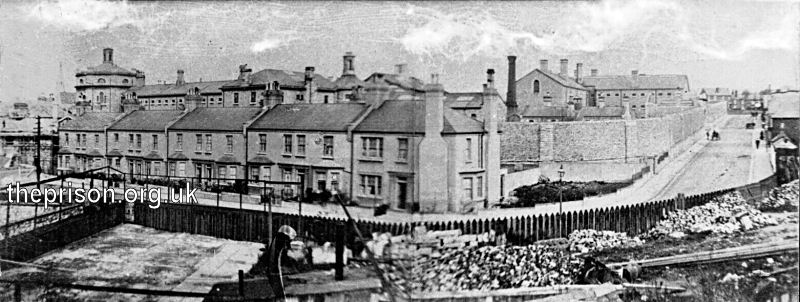

HMP Maidstone, aerial view from the west. © Peter Higginbotham

HMP Maidstone, c.1905.

The prison is still in operation. It is now classed as a training prison, largely being used to hold foreign nationals convicted of a variety of offences, with many being deported at the end of their sentence. The only parts of Alexander's original buildings to survive are the large roundhouse that lay at the centre of the complex, and the blocks that formed the southern cross.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- Kent History and Library Centre, James Whatman Way, Maidstone, Kent ME14 1LQ Holdings include: Convict book — a register of all convicts, arranged annually by Sheriffs (1805-33); Prison registers (from Canterbury and Maidstone prisons, though not always clear which prison for each book, 1880-1900).

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Has a wide variety of crime and prison records going back to the 1770s, including calendars of prisoners, prison registers and criminal registers.

- Find My Past has digitized many of the National Archives' prison records, including prisoner-of-war records, plus a variety of local records including Manchester, York and Plymouth. More information.

- Prison-related records on

Ancestry UK

include Prison Commission Records, 1770-1951

, and local records from London, Swansea, Gloucesterhire and West Yorkshire. More information.

- The Genealogist also has a number of National Archives' prison records. More information.

Census

Bibliography

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.