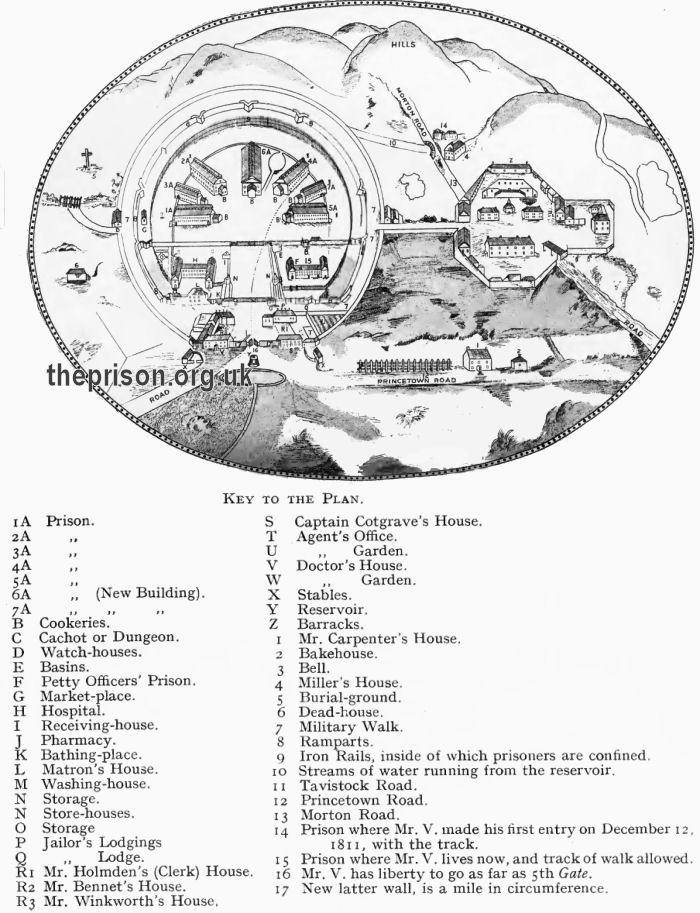

Dartmoor Prisoner of War Camp, Princetown, Devon

Overcrowding at the Stapleton and Norman Cross prisons and aboard the hulks at Plymouth resulted in the building of a large new prison at Princetown on Dartmoor. The site chosen was near to granite quarries which supplied stone for construction of the prison, which was designed by Daniel Asher Alexander. The first stone of the new buildings was laid on 20 March 1806.

The prison covered thirty acres and was enclosed by stone walls, the outer of which was sixteen feet high, and was separated by a broad military way from the inner wall, which was hung with bells on wires connected with all the sentry boxes dotted along it. One half of the circle thus enclosed was occupied by five huge barracks, each capable of holding more than 1,000 men, with their airing grounds and shelters for bad weather, and their inner ends converging on a large open space, where a daily market was held. Each barrack, or caserne, consisted of two floors, and above the top floor ran, the length of the building, a roof room, designed for use when the weather was too bad even for the outdoor shelters, but which came to be appropriated for other purposes. On each floor, a treble tier of hammocks was slung on cast-iron pillars. Each barrack had its own airing ground, supply of running water, and Black Hole, or punishment cell. The other half-circle was occupied by two spacious blocks, one the hospital, the other the petty officers' prison, by the officials' quarters, the kitchen, washing houses, and other domestic offices, and outside the main, the Western Gate, the barrack for 400 soldiers and the officers' quarters. The cost of the prison was £135,000.

Dartmoor Prisoner of War Camp, Princetown, Devon, 1812.

The first prisoners arrived on 24 May 1809. Two months later, the first escape occurred when two prisoners bribed the sentries, men of the Nottinghamshire Militia. The Frenchmen were soon recaptured. The soldiers, four in number, confessed they had received eight guineas each for their help, and two of them were condemned to be shot.

Within a few months of its opening, the prison was home to about 5,000 French prisoners. At its height, the number of inmates was over 8,000.

The clothing of the prisoners consisted of a cap of wool, one inch thick and coarser than rope yarn, a yellow jacket not large enough to meet round the smallest man, although most of the prisoners were reduced by low living to skeletons with the sleeves half-way up the arms, a short waistcoat, pants tight to the middle of the shin, shoes of list with wooden soles one and a half inches thick.

The inmates' diet was rather better than that received by many of those being held in England's civilian gaols. The food was provided by private contractors. The daily ration for Dartmoor's healthy prisoners is shown below.

| Sunday Monday Tuesday Thursday Saturday |

One pound and a half of bread. Half a pound of fresh beef. Half a pound of cabbage or turnips fit for the copper. One ounce of Scotch barley. One-third of an ounce of salt. One-quarter of an ounce of onions. |

| Wednesday | One pound and a half of bread. One pound of good sound herrings (red herrings and white pickled herrings to be issued alternately). One pound of good sound potatoes. |

| Friday | One pound and a half of bread. One pound of good sound dry cod fish. One pound of good sound potatoes. |

Despite the relatively good fare provided to the Dartmoor inmates, food was still the cause of problems, particularly amongst a group of French prisoners known as the 'Romans'. These were largely men who, because of the gambling that was rife in the prison, had literally lost their shirts — together with their bedding, and any other possessions. Such men formed a commune in the large lofts beneath the prison roofs which had been intended to provide exercise space during bad weather. The Romans rarely tasted the prison's official dietary:

From morning till night groups of Romans were to be seen raking the garbage heaps for scraps of offal, potato peelings, rotten turnips, and fish heads, for though they drew their ration of soup at mid-day, they were always famishing, partly because the ration itself was insufficient, partly because they exchanged their rations with the infamous provision-buyers for tobacco with which they gambled. In the alleys between the tiers of hammocks on the floors below you might always see some of them lurking, if a man were peeling a potato a dozen of these wretches would be round him in a moment to beg for the peel; they would form a ring round every mess bucket, like hungry dogs, watching the eaters in the hope that one would throw away a morsel of gristle, and fighting over every bone.

After the prison's own bakehouse was burned down in October 1812, the prisoners refused to accept the bread sent in from Plymouth by the contractor, claiming that it was damp and sour. After satisfying himself that the bread was of good quality, the prison's governor, Captain Isaac Cotgrave, announced that any man who refused the bread would forfeit the ration for that day. According to one account, the starving Romans:

Fell upon the offal heaps as usual, and when the two-horse waggon came in to remove the filth they resented the removal of their larder. In the course of the dispute, partly to revenge themselves upon the driver, partly to appease their famishing bloodthirst, these wretches fell upon the horses with knives, stabbed them to death, and fastened their teeth in the bleeding carcases. This horror was too much for the stomachs of the other prisoners, who helped to drive them off.

A rather more salubrious part of the premises, known as the Petty Officers' prison, housed French naval and merchant service officers. Many were fairly well-to-do men who were able to buy provisions from the daily market and also hire prisoners from other sections to perform menial tasks such as cleaning for them. Even here, though, life was not uneventful:

One day at dinner a man pulled out of the soup bucket of his mess a dead rat which he held up by the tail, whereupon heads and tails and feet were dredged up from every bucket in such numbers that they would have furnished limbs for fully a hundred animals. We may judge whether the regulation diet of the prisoners was sufficient, from the fact that out of all these Frenchmen of the middle classes only a handful of the most squeamish went without their soup that day. For a time the life of the cooks hung by a thread, and it was only upon the intervention of the Commissaire that the head cook was allowed to speak in his own defence. The coppers, as it seemed, had been filled with water overnight as usual, but through forgetfulness the covers had not been closed, and the coppers had thus been converted into rat traps. It had not occurred to the cooks to dredge them for dead bodies, and the meat and vegetables had been thrown in atop and the fires lighted.

Naturally enough, some foreign prisoners attempted to recreate their home cuisine. Some of the more enterprising French inmates 'opened booths for the sale of strange and wonderful dishes compounded of the Government rations with ingredients purchased in the market. The favourite was a ragout, called "ratatouille," made of Government beef, potatoes and peas.' When American prisoners came to Dartmoor, some shaved a thin layer from the crust of their bread which was then scorched over coals to make a form of coffee.

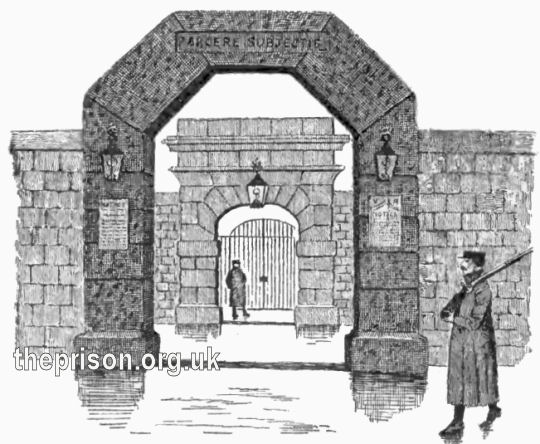

Original entrance gate to Dartmoor Prison, Princetown, Devon.

An extension to the buildings was used to hold captives from the Anglo-American war of 1812-15. On 2 April 1813, their numbers were increased when American prisoners being held on prison hulks, were ordered to be transferred to Dartmoor because of their ceaseless efforts to escape. Around 900 came from Chatham, 100 from Portsmouth, and 700 from Plymouth, most of them destitute of clothes and swarming with vermin. From the Plymouth hulks Hector and Le Brave, 250 were landed at New Passage, and marched the seventeen miles to Dartmoor, where were already 5,000 French prisoners. On 1 May 1813, Captain Cotgrave ordered all the American prisoners to be transferred to No. 4 block where there were already 900 French 'Romans'. On 18 May, 250 more Americans came from the Hector hulk, and on 1 July, 100 more.

The militia garrison at Dartmoor consisted of from 1,200 to 1,500 men, who had mostly been given this duty as punishment for their own offences. The manning of the garrison at all the war prisons was frequently changed as it was believed that an undesirable intimacy often developed between the guards and those they guarded. The guards feared the American prisoners more than the French. From the hulks came warnings of their skill and ingenuity, their courage, and their frantic endeavours to regain liberty. As a result, the Americans were badly treated. The prison medical officer, named Dyer, took notice of no sickness until it was too far gone to be treated, and refused patients admission to the hospital until the last moment: for fear, he said, of spreading the disease. They were also denied many privileges and advantages allowed to Frenchmen of the lowest class; they were shut out from the usual markets, and had to buy goods through the French prisoners, at 25 per cent, above market prices.

The date of 4 July 1813 was a dark day in the history of the prison. The Americans, who wished to hold an Independence Day celebration, obtained two flags and asked permission to hold a quiet festival. Captain Cotgrave refused, and sent the guard to confiscate the flags. Whn resistance was offered, there was a struggle and one of the flags was captured. In the evening the disturbance was renewed, an attempt was made to recapture the flag, the guard fired on the prisoners and wounded two. A growing antipathy between French and American prisoners boiled over on July 10, when the 'Romans' in the two upper stories of No. 4 block collected a variety of makeshift weapons and launched a surprise attack on the Americans, with the avowed intent of killing them all. A bloody battle ensued, with the priosn guards eventually intervening to separate the two parties, though only after forty on both sides had been badly wounded. After this, a wall fifteen feet high was built to divide the airing ground of No. 4.

Originally, negroes, who formed considerable part of American crews, were mixed with the white men in the prisons. However, they were housed separately following a petition from the American white prisoners that black inmates should be confined by themselves, as they were said to be dirty by habit and thieves by nature.

Gradually, the official fear of the Americans' determination to obtain liberty subsided, and their treatment became more relaxed. A coffee-house was established, trades sprang up, markets for tobacco, potatoes and butter were carried on, the old French monopoly of trade was broken down, and the American prisoners imitated their French companions in manufacturing all sorts of objects of use and ornament for sale. The French prisoners by this time were quite well off, their straw-plaiting for hats bringing in threepence a day, although it was a forbidden trade, and plenty of money being found for theatrical performances and amusements generally. The condition of the Americans, too, kept pace, with improved money allowances, so that each prisoner received 6s. 3d. per month, the result being a general improvement in their outward appearance.

On May 20, 1814, peace between England and France was announced amidst the frenzied rejoicings of the French prisoners. All Frenchmen had to produce their bedding before being allowed to go. One poor individual failed to comply, and was so frantic at being turned back, that he cut his throat at the prison gate. Some 500 men were released, and with them some French-speaking American officers got away. When this was followed by a rumour that all the Americans were to be removed to Stapleton, where there was a better market for manufactures, and which was far healthier than Dartmoor, the tone of the prison was quite lively and hopeful. This rumour, however, proved to be unfounded, but it was announced that henceforth the prisoners would be occupied in work outside the prison walls, such as the building of the new church, repairing roads, and in certain trades.

Two desperate and elaborate attempts at escape by tunnelling were made by American prisoners in 1814. Digging was done in three barracks simultaneously — from No. 4, in which there were 1,200 men, from No. 5, which was then empty, and from No. 6, lately opened and now holding 800 men — down in each case twenty feet, and then 250 feet of tunnel in an easterly direction towards the road outside the boundary wall. On 2 September, Captain Shortland, the new governor, discovered it; some say it was betrayed to him, but the prisoners themselves attributed it to indiscreet talking. The enormous amount of soil taken out was either thrown into the stream running through the prison, or was used for plastering walls which were under repair, coating it with whitewash. When the excitement of this discovery had subsided, the indefatigable Americans got to work again. The discovered shafts having been partially blocked by the authorities with large stones, the plotters started another tunnel from the vacant No. 5 prison, to connect with the old one beyond the point of stoppage. It was planned to tunnel under the boundary walls and then, armed with daggers forged at the blacksmith's shop, to emerge on a stormy night and make for Torbay, where there were believed to be fishing boats sufficient to take them to the French coast. No-one was to be taken alive. However, the scheme was betrayed by an American prisoner named Bagley who, to save him from the fury of the other prisoners, was liberated and sent home. Following these escape efforts, the prisoners were confined to Nos. 2 and 3 barracks, and put on two-thirds ration allowance to pay for the damage that had been done.

In October 1814, eight Americans escaped by bribing the sentries to procure them military coats and caps, and so getting off at night. Much amusement was caused one evening by the ringing of the alarm bells, the hurrying of soldiers to quarters, and subsequent firing at a 'prisoner' escaping over the inner wall the 'prisoner' being a dummy dressed up.

In November, 5,000 more prisoners came into the prison. There was much suffering among the inmats that winter from their cold and scanty clothing. A petition to have fires in the barracks was refused. A man named John Taylor, a native citizen of New York City, hanged himself in No. 5 prison on the evening of 1 December.

Peace, which had been signed at Ghent on December 24, 1814, was declared at Dartmoor, and occasioned general jubilation. Flags bearing the words 'Free Trade and Sailors' Rights' were paraded with music and cheering. Unfortunately, much suffering took place between the date of the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent in March, 1815, and the final departure of the prisoners. The Americans' London-based Agent, Reuben Beasley, who was supposed to monitors prison conditions, was negligent and tardy in his arrangements for the reception and disposal of the prisoners. Although by rights they were free men, in practice they were still detained and treated as prisoners. Small-pox broke out, and it was only by the unwearying devotion and activity of Dr. Magrath, the prison surgeon, that the epidemic was checked, and that the prisoners were dissuaded from going further than giving Beasley a mock trial and burning him in effigy.

Worse was to come, however. On 4 April 1815, the provision contractors tried to off-load their stock of biscuit by serving it out to the prisoners instead of the fresh bread they were entitled to. The Americans refused to accept it, swarmed round the bakeries, and refused to disperse when ordered to. Captain Shortland was away in Plymouth at the time, and the officer in charge, deciding that it was useless to attempt to force them with only 300 Militia at his command, yielded, and the prisoners got their bread. When Shortland returned, he was very angry at what he that his subordinate had so readily caved in, swore that if he had been there the Yankees should have been brought to order at the point of the bayonet, and he determined to create an opportunity for revenge. This came on 6 April 6, when some boys playing in the yard of No. 7 caserne, knocked a ball over into the neighbouring barrack yard. When the sentry on duty there refused to throw it back,they made a hole in the wall, crept through it, and retrieved the ball. Shortland pretended to view the holemaking as a plan to escape. He ordered the alarm bell to be rung and when many of the prisoners had emerged from their quarters he ordered one of the two doors in each caserne to be locked. In the market square, several hundred soldiers, with Shortland at their head, were then ordered to charge the prisoners assembled there. The consequent confusion among hundreds of men vainly trying to get into the casernes by the one door of each left open, and being pushed back by others coming out to see what was the matter, was wilfully magnified by Shortland into a concerted attempt to break out, and he gave the word to fire. According the American accounts, seven men were killed, thirty were dangerously wounded, and thirty slightly wounded.

A rapidly conducted inquiry into what became known as the 'Dartmoor Massacre' reached no satisfactory conclusion. It was evident, said its report, that the prisoners were in an excited state about the non-arrival of ships to take them home, and that Shortland was irritated about the bread affair; that there was much unauthorized firing, but that it was difficult exactly to apportion blame. Shortland was effectively exonorated, having justified the initial shooting and blaming the subsequent deaths on unknown culprits. The report was utterly condemned by the committee of prisoners, who resented the tragedy being referred to as 'this unfortunate affair', and complained of the hurried and imperfect way in which the inquiry was conducted and the evidence taken.

On 20 April 1815, 263 ragged and shoeless Americans left Dartmoor, leaving 5,193 behind. The remainder followed in a few days, marching to Plymouth, carrying a huge white flag on which was represented the goddess of Liberty, sorrowing over the tomb of the killed Americans, with the legend: 'Columbia weeps and will remember!'

In July 1815, the last Dartmoor war prisoners arrived —, 4,000 Frenchmen taken at Ligny. These were easy to manage after the Americans; 2,500 of them came from Plymouth with only 300 Militiamen as guard, whilst for Americans the rule was man for man.

The final prisoners left Dartmoor in December 1815. The site was then unoccupied until 1850 when it taken over for use as the Dartmoor Convict Prison.

Records

Note: many repositories impose a closure period of up to 100 years for records identifying individuals. Before travelling a long distance, always check that the records you want to consult will be available.

- The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. Has Registers of American and French Prisoners of War at Dartmoor.

- Plymouth and West Devon Record Office, The Box, Tavistock Place, Plymouth, Devon PL4 8AX. Microfilm of indexes to American and French Prisoners of War at Dartmoor.

- Find My Past has an extensive collection of Prisoner of War records from the National Archives covering both land- and ship-based prisons (1715-1945).

Bibliography

- Abell, Francis Prisoners of War in Britain 1756 to 1815 (1914, OUP)

- Higginbotham, Peter The Prison Cookbook: A History of the English Prison and its Food (2010, The History Press)

- Brodie, A. Behind Bars - The Hidden Architecture of England's Prisons (2000, English Heritage)

- Brodie, A., Croom, J. & Davies, J.O. English Prisons: An Architectural History (2002, English Heritage)

- Harding, C., Hines, B., Ireland, R., Rawlings, P. Imprisonment in England and Wales (1985, Croom Helm)

- McConville, Sean A History of English Prison Administration: Volume I 1750-1877 (1981, Routledge & Kegan Paul)

- Morris, N. and Rothman, D.G. (eds.) The Oxfod History of the Prison (1997, OUP)

- Pugh R.B. Imprisonment in Medieval England (1968, CUP)

Links

- Prison Oracle - resources those involved in present-day UK prisons.

- GOV.UK - UK Government's information on sentencing, probation and support for families.

Except where indicated, this page () © Peter Higginbotham. Contents may not be reproduced without permission.