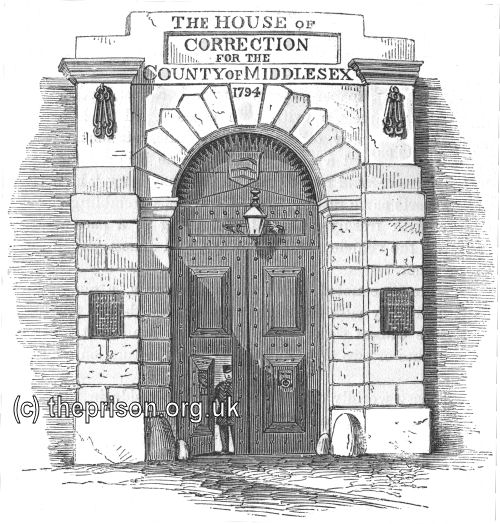

Middlesex County Bridewell, Coldbath Fields, Clerkenwell, London

In the reign of James I, Middlesex erected a Bridewell, or House of Correction, at Coldbath (or Cold Bath) Fields, an area lying between Clerkenwell and Pentonville. It was established to deal with the increase of vagabondage, which had become so great at that time, that the City Bridewell could no longer accommodate the number of offenders. The judges therefore built this prison, the City authorities giving £500 towards it, for keeping their poor employed.

A new prison was erected in 1788-94, on an area of former swamp-land at the north side of Bayne's Row, now Mount Pleasant. The land, purchased for the purpose by the county magistrates, cost £4,350; and the original building was constructed at a cost of £65,656. Although this was a massive sum at the time, the building provided only 232 cells, each then being used to house three inmates.

The prison site is shown on the 1827 map below.

Middlesex County Bridewell site, Clerkenwell, c.1827.

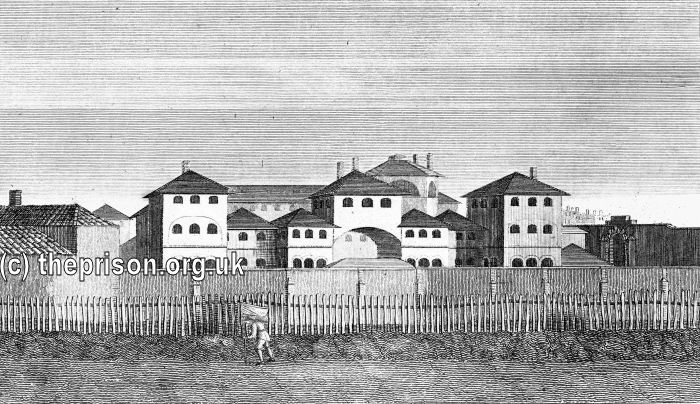

Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1794. © Peter Higginbotham

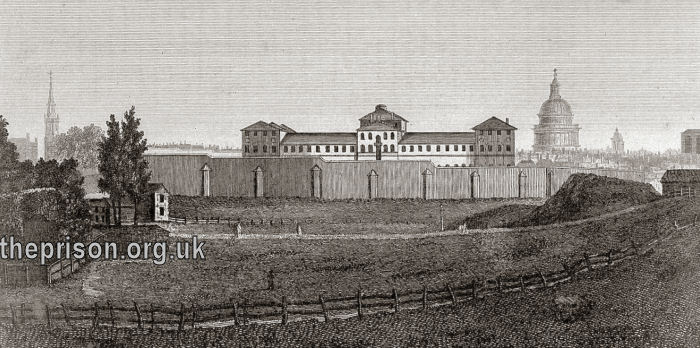

Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1798.

Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1828.

Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

In 1812, James Neild wrote:

The Prison of Cold Bath Fields stands in front of Bayne's Row. The entrance to it is the main gate, with the First Turnkey's room adjoining; from whence a court-yard, of about 35 feet, leads on to the Inner Turnkey's Lodge.

From the iron rails next the Gaoler's house, to those nearest the Prisoner's workyard, is another court, 48 feet in length, paved with stone, which forms a carriage way into the Prison.

At the end of the court-yard next the main gate, stands the Inner Turnkey's lodge, which has two rooms above it. The gateway below, leading on to a courtyard in front of the office, of about 28 feet by 12 feet 9 inches wide, is paved with broad Purbeck stone, and has an iron gate, with a wooden one also across it.

The former gate is where the friends of Prisoners are admitted who come to visit them, and stands about four feet distant from the wooden gate, at which the Prisoners are allowed to receive their friends; both gates being under cover, and having between them a door belonging to the Inner Turnkey's lodge.

Another court-yard, of 45 feet by 42, leads from the last-mentioned lodge, and extends to the front of the Turnkey's office. The office itself, 15 feet by 14 feet 6, has two rooms above it: one of them is for the Gaol Committee; and over it is the Store-keepers apartment, 17 feet by 16.

A passage of 5 feet 9 inches wide, reaches from the court-yard just noticed, to the kitchen. The Chapel, which is above the passage, and in the centre of the whole building, is so constructed as to receive all the six classes of Prisoners, male and female; and contains, also, a pew for the Magistrates, the Communion Table, and seats for the Keeper and Turnkeys. On the 19th of June, 1808, I attended Divine Service here, when all the Prisoners were cleanly in their persons, and decently attentive to a very suitable discourse.

The kitchen, 33 feet by 32, is furnished with two cast-iron boilers, for the use of the Prisoners.

In the interior of the Gaol are eight other court-yards, extending each about 66 feet from the doors to the water-closets in them, and from the front of the cells to the back-wall of the Colonnades, 32 feet 6 inches wide. These courts contain each from seven to nine cells, and a water-closet. The staircases to the different apartments are about five feet wide, and the several passages to the galleries and cells,, about 4 feet 6 inches.

Next the garden grounds also are eight smaller court-yards, about 41 feet by 23, surrounded by iron rails; and a ninth, 16 feet 6 by 13 feet 10. These are all appropriated to the Prisoners for taking air and exercise.

A spacious garden is thrown round the whole Prison, and extends to the boundary wall on all sides. On the right-hand from the Main-Gate is the Gaolers House, which I am given to understand was built by the Prisoners here confined, and contains two cellars, and as many kitchens, a water closet, two parlours, and the Keeper's office. On the first-floor are a drawing-room, dining ditto, and a bedchamber; on the second-floor, three bed-rooms, the house is enclosed within a small iron palisade, and a gate (said also to have been made by the Prisoners): And on the right of the Inner Turnkey's lodge is the Keeper's wash-house, with coppers, and other utensils.

On the left of the Main-Gate is the working-yard, containing sheds for coals, and a large one for the drying of oakum; under which last is sunk a capacious saw-pit, and nearly adjoining, on the left of the Inner Turnkey's lodge, are placed an oven for fumigating clothes, with various shops for shoe-makers, taylors, blacksmiths, and other handicraft Prisoners.

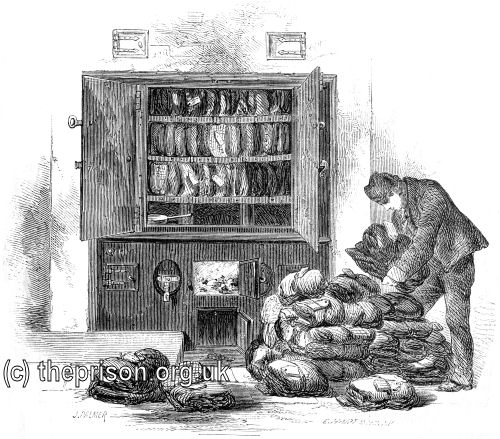

Fumigation room at Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

The garden is cultivated, sown, and planted with different kinds of vegetables for the use of the Prisoners, and the labour of it is done by themselves, under the Gaoler's direction. The Gaol is white-washed at least twice a year, which is also performed by the Prisoners; and it is supplied with water plentifully from a well on the East-side, which is carried to different parts of the building,: by means of an engine occasionally set to work by two of the Prisoners. Here is also a large workroom at the top over the well, of 27 feet 10 inches by 29 feet 3 inches wide.

The Debtors here have, on the Eastern-side of the Prison, a court-yard, 35 feet by 20; a day-room about 12 feet square; and two sleeping-cells, 7 feet by 5 feet 6 inches on the first story, furnished with wooden bedsteads, a straw-in-ticking bed, one blanket in Summer, two in Winter, and a rug each. The County humanely allows them a peck of coals per day.

On the South-west Side, being the department of the Females, is a small well, supplied from the one before-mentioned, to serve this part of the Prison; which is done by an engine set to work by the disorderly Females. Over this well, likewise, there is a large work-room of the same dimensions as the former; and also a courtyard, of 37 feet 9 inches by 28 feet, in which are the Turnkey's apartments.

At the South-corner is the general laundry, or wash-house, with copper, washing troughs, &c. in which the Female Criminals are employed to wash and get up the linen of the Prisoners at large. Here is also a drying-yard next the garden, of 41 feet by 23, and another for the like purpose, of 13 feet 10. Over the wash-house is a work-room for the Females, 25 feet by 15; and above this, at the top of the building, is the Female Infirmary, of the same dimensions.

At the East-corner is a day-room, for the first class of Male-Felons, about 23 feet square; over which, on the first floor, is another day-room, set apart for the aged and infirm Prisoners, of like dimensions; and above all these, on the top of the Prison, is the Male Infirmary.

The number of cells was 366, each 6 feet 3 inches wide by 8 feet 3 inches long, and 11 feet high. Of these, ten are solitary cells; and four of the others have been laid into two: so that the original number of sleeping-cells is at present reduced to 354.

The distribution of employment into its various branches is as follows, and deserves to be recorded; viz.

- White-washing and painting the Prison.

- Washing and mending the Prisoners' linen.

- Making and mending their clothes and shoes.

- Carpenters' and Smiths' work for the Gaol.

- Making rope and spun-yarn, and spinning tow.

- Knotting yarn, and picking oakum.

- Working in the garden, and at the water-engines.

- Sweeping and cleaning the Prison; and

- Attending as Nurses to the Infirm and Sick.

The Prisoners (except such only as stand on the Surgeon's List,) are constantly engaged at their several occupations; and, during the hours of labour, are kept as much separated as the nature of their respective employments will admit. Of their earnings they are allowed one sixth part, or two-pence in every shilling; which they receive at the expiration of their Term of Imprisonment, and are then discharged without paying Fees. N.B. No Prisoner who appears to be distressed, is sent forth, without first receiving some relief, either in money or clothes; and sometimes they have both.

| Table of the Fees | |

| To be taken by the Keeper of Cold-Bath-Fields Prison, or House of Correction, at Clerkenwell, in the County of Middlesex. | |

| s. d. | |

| For keeping and discharging every person committed by a Warrant of Commitment | 4 6 |

| For turning the Key at every such Person's Discharge | 1 0 |

| For a Copy of Commitment | 1 4 |

| For going with any Person before a Justice | 1 0 |

| Prisoners brought in by Constables of the Night, and carried before Justices of the Peace | 2 0 |

| By the Court, | |

| BUTLER. | |

At the South-west front of this Prison are two store-rooms, for depositing the different articles of provision, clothing, bedding, &c. for the use of the Prisoners; and also for laying by the clothes of such as are convicted, from Session to Session, either at Justice-Hall, in the Old Bailey, or from other of His Majesty's Courts belonging to the County of Middlesex: which clothes, upon the Prisoners' coming in, are examined; and, if found in an offensive state, are fumigated, washed, and carefully kept separate, till the time of their discharge. Frequently, however, they enter the Prison so wretchedly equipped, that their apparel is obliged to be destroyed.

Since writing the above account some alterations have taken place; viz. A room, heretofore used as a store-room, has been turned into a day-room for Male-Prisoners detained for misdemeanours, which was much wanted. The number of day-rooms is thus increased to seventeen, and there is a fire-place in each.

The Old Infirmary-rooms have been converted into foul-wards; and two new Infirmaries, (large and airy apartments,) are built over the tanks, or wells. All the sewers have been turned into water-closets, and cisterns very properly constructed for their supply.

A new stove has been put up in the Chapel, which is thus rendered warm and comfortable.

There are still some other improvements which this Prison is very capable of receiving; and after being specified in detail by the judicious Commissioners appointed to examine into the state of it, they will, no doubt, be readily adopted by the considerate Magistrates of the County of Middlesex.

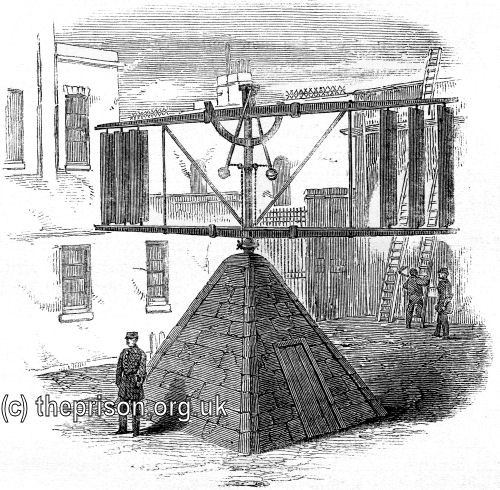

In December 1822, the tread-wheel was introduced at the prison. Wheels were erected in eight of the yards so that, with relays, more than three men could be kept employed for eight hours a day. The turning of the wheels was used to grind flour. The speed of the wheels was regulated by a large rotating fan.

Also in 1822, it was reported that the prison was very full, sometimes having more than twice the number of inmates that the building was originally designed for. It was particularly bad for the women, for whom the lack of space meant that no classification was possible, so that first offenders were mixed with hardened bad characters. They also had no matron or female officers to attend them.

In 1829, George Laval Chesterton took over as Governor of the prison. He later recalled the state of things when he arrived:

It was a sink of abomination and pollution; and so close was the combination amongst its corrupt functionaries, that it was difficult to acquire any definite notion of the wide-spread defilement that polluted every hole and corner of the Augean stable. There was scarcely one redeeming feature in the prison administration, but the whole machinery tended to promote shameless gains by the furtherance of all that was lawless and execrable.

Each "turnkey" had a fixed locality, and was the supervisor of a yard containing from 70 to 100 prisoners, while every yard contained a "yardsman," i.e., a prisoner who could afford to bid the highest price for acting as deputy-turnkey, and, under his superior, to trade with the prisoners at a stupendous rate of profit to his principal and to himself. Prisoners also occupied the lucrative posts of "nurses" in the infirmary, while those of "passage-men," and other still more subordinate capacities, procurable by money, all tended to enrich the officers and the chosen prisoners at one and the same time.

From one end of the prison to the other, there existed a vast illicit commerce at an exorbitant rate of profit. The basement of all the cells was hollowed out and made the depositories of numerous interdicted articles. Layers of lime-white, frequently renewed, hid beneath the surface an inlet to such hidden treasures; and thus wine and spirits, tea and coffee, tobacco and pipes, were unsuspectedly stowed away, and even pickles, preserves, and fish sauce, might also be found secreted within those occult receptacles. The walls, too, separating one cell from another, were adapted to like clandestine uses, the key to such deposits being merely a brick or two easily dislodged by any one acquainted with the secret.

In vain might a magistrate penetrate into the interior of the prison, and cast his inquisitive glances around him. Telegraphic signals would announce the presence of an unwelcome visitor, and all be promptly arranged to defeat suspicion. The prisoners would assume an aspect and demeanour at once subdued and respectful; the doors of cells would fly open to disclose clean basements, edged with thick layers of lime-white (deliberately used to conceal the secrets beneath), pipes would be extinguished and safely stowed away, the tread-wheels fully manned, and other industrial arts set in motion.

The first question addressed to a prisoner on his arrival was, "had he money, or any thing convertible into money, or would any friend supply him with money." If the reply were affirmative, the turnkey, or some agent of his, would convey a letter for the requisite contribution, which became subject to the unconscionable deduction of seven or eight shillings, out of every pound sterling transmitted, besides a couple of shillings to the "yardsman,"and, in many instances, an additional shilling to the "passage-man."

The poor and friendless prisoner was a man wretchedly maltreated and oppressed. Every species of degrading employment was thrust upon him, and daily inflictions rendered his existence hardly supportable. If he presumed to complain, the most inhuman retaliation awaited him. He was called "a nose," and was made to run the gauntlet through a double file of scoundrels armed with short ropes or knotted handkerchiefs.

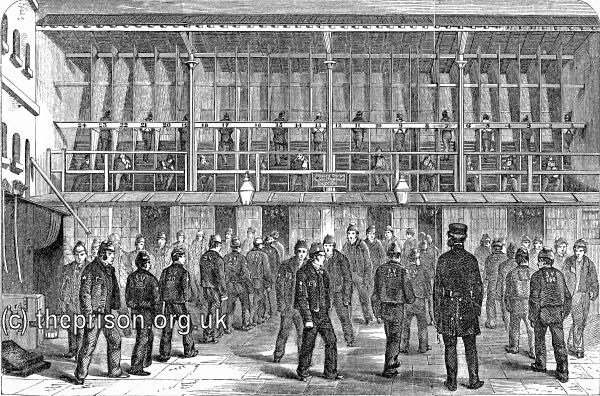

Within a few years, Chesterton had managed to bring the prison into line. One of the most effective changes was the introduction in 1834 of the 'silent system', under which 'all intercommunication by word, gesture, or sign, was prohibited.' Achieving this required adaptations to the sleeping arrangements. Extra accommodation was created by enclosing the space under each set of tread-wheels, which were erected on elevated platforms. The previous day-rooms, and every spare room throughout the great building, were then adapted to sleeping by the construction of berths in three tiers, as used on passenger ships. Opposite to these, a monitor slept on an iron bedstead. A night watchman was also able to inspect each room from outside.

Chesterton also discovered that, despite the considerable cost of the original building, some of the construction work had been badly done. In 1833, following a major cholera outbreak in the previous year, an inspection of the prison's sewers revealed that the support arches, which ought to have been turned with cement, had been so loosely constructed, that the bricks had fallen in, choked up the outlet for impurities, and stagnant accumulations had undoubtedly engendered cholera, and, for a time, delayed its eradication.

A building to house up to 150 vagrants was erected at the south-west corner of the site in 1830, followed by one for 300 female prisoners in 1832. Both of these adopted a radial layout, with cell wings emanating from a central hub.

In 1850 the Middlesex Justices decided that Coldbath Fields should be used only for convicted male prisoners aged 17 or over. Thereafter, convicted female prisoners and males under 17 were sent to the Westminster House of Correction at Tothill Fields.

An extensive description on the prison from 1862, considerably abridged, is reproduced below:

Interior of the Prison.

We entered a stone-paved yard, on one side of which stood the gate-warder's lodge, and on the other stretched out a gravelled court. A canopy of glass, like the roof of a green house, was suspended in the air like an awning, and covered in the path leading to an iron double gate, which lay some twenty feet off in front; the little yard was hemmed round with thick railings and massive gates, through which we could distinguish the governor's house and the protruding sides of the main prison itself, with its small heavily-barred windows. The detached clump of buildings between us and the main prison seemed more like a private residence than part of a prison; and on inquiry it was explained to us, that the erection was that in which the clerk's and governor's offices, the visiting magistrates' committee-rooms, as well as the armoury and the record office, were situated.

The gate-warder stood by with the bright key inserted in the lock, as the officers entered, ready to turn the bolt at the first order. We were not long before we made the acquaintance of the deputy-governor, who, in full uniform, with a crimson shield and gold sabre on his collar, and gold band round his cap, came out to review the warders before they began the duties of the day.

This examination over, the double iron-gratings were unlocked, and passing through the passage in the centre clump of buildings, we entered the flag-stoned yard facing the main or felons' prison.

There was no doubt now as to the nature of the edifice before us. The squat front of the whitewashed two-storeyed building was so devoid of any attempt at ornament, that even the small windows with the heavy black gratings before them seemed reliefs to its monotonous aspect. A few stone steps led to a low wicket with a row of spikes on its thick swing door, the spikes being so arranged that they reached within two inches of the thick cross bars fixed in the circular fan-light over it.

A gang of prisoners, dressed in their suit of dusty gray, now issued from the main building and crossed the yard, with a warder following them. On the back of each criminal was a square canvas tablet stitched to the jacket, and on the bosom was a long badge worn something like that of a cabman. Each of the wretched men, as he descended the stone steps, and caught sight of the deputy-governor, held up his hand to his worsted cap and gave a half military salute. "They are vagrants and reputed thieves," explained the officer; "but for want of room in the vagrants' ward they have been sleeping in the felons' cells.

The Interior of the "Main"

All confined within the main prison have, as we have said, been convicted as felons. Ascending the stone steps we passed down a few paces of passage, when a second wicket, similar to the first, was unlocked to admit us. We now stood in a kind of hall about forty feet square, in the centre of which were four stout iron pillars, "to support," as we were told, "the chapel above." This vestibule was so bright with whitewash, that the light reflected was almost painful to the eyes. On the walls were large paper placards printed in bold type, with religious texts. One was as follows: — "CONSIDER YOUR WAYS, FOR YE SHALL ALL STAND BEFORE THE JUDGMENT SEAT OF CHRIST." Another ran — "SWEAR NOT AT ALL," which, in a prison conducted on the silent system, struck us as being somewhat out of place. Whilst a third contained the curiously inappropriate quotation — "BEHOLD HOW GOOD AND HOW PLEASANT IT IS FOR BRETHREN TO DWELL TOGETHER IN UNITY." At each corner of this hall there was a gate of thick iron bars leading to the prisoners' cells.

This main building contains eight yards, each one holding from a hundred to a hundred and fifteen prisoners, all felons. The deputy-governor, unlocking one of the strong iron gates in the corner, led us into what is called the first yard. It was an oblong open space, about the size of a racket-ground, lying parallel with the outer wall, or front, of building, and at right angles with the passage. On one side was what appeared two low wooden sheds built one above the other, and each with long glazed lights running the entire length of the buildings; the under one being the meal-room, and the upper a spare dormitory, at present out of use. Facing these sheds was a row of doors leading, as we found, to the sleeping cells. The doors, with the black bolts drawn back, and the cross-bars slanting upwards, were half opened, showing the inmates had left the cells. Over each door was a massive half-circular grating let into the stone wall, and by means of which the light entered when the men were locked up for the night; whilst at the further end, ranged on one side of the doorway leading to the galleries above, were six slate washing-stands for the use of the prisoners.

Those of the prisoners who slept in the dormitories and cells, in the upper part of the prison, were entering by the last-mentioned door, in a long file, each carrying a wooden tub, which, as he passed a sink in the centre of the yard, he emptied, and then added the vessel to a pile that kept rapidly increasing in height as one after another went by. Then, still continuing in line, the prisoners entered the wooden shed. These men carried also a bundle composed of a towel, a comb, and Bible, Prayer, and reading book.

The place, as we entered, was silent as a deserted building. The deputy-governor having counted the prisoners, called out the number, and the sub-warders having answered "Right," an entry was made in a book, and the felon's morning toilet commenced. The men took off their coats and opened their blue shirts. Directly the sombre gray clothes were removed, it was strange how altered the appearance of the prisoners became. The colour of the flesh gave them once more a human look.

Twelve at a time they rose and entered the yard. Then, some at the slate lavatories, others at tubs placed on the paved ground, began to soap their neck and faces, and rub them with their wet hands until they were white with the lather. But a few minutes were allowed to each gang, and at the expiration of the time they returned to the shed, there to adjust their shirts, comb their hair, and put on their jackets. Whilst these operations were going on the iron-barred door of the yard opened, and a prisoner, bearing a tin can entered, accompanied by the infirmary warder. This can contained poultices, and the man called out aloud, "Any want dressings?" A lad, with sores in his neck, had a soda-water bottle given to him, filled with a gray-coloured wash, and he entered a cell to apply the medicine.

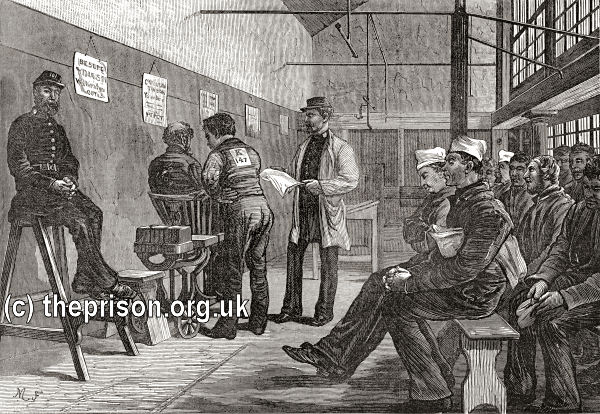

Arrival of Prisoners.

When the prison-van is seen driving in the direction of the House of Correction, a crowd begins to form outside, in the hope of catching a glimpse of the prisoners alighting.

One by one the men stept out, with a half bound, as if glad to have ended their cramped ride. They stared about them for second, to see what kind of place they had arrived at, and then, obeying the warder's commanding voice, they passed the double iron gate, where the visits take place, and entered the inner court. There they stood with their backs turned to the main prison, waiting for their names to be called over, and their sentences and offences entered in the prison books.

Presently the voice of the chief warder was heard ordering the first man to enter the office, where the clerk was to make the necessary entries. The tall, stout man, with the silver spectacles, walked up to the desk, and the examinations commenced in a business-like manner, the questions and answers being equally short. "Name?" asked the chief warder. "J— C—," answered the prisoner. "Age?" continued the officer. "Thirty-nine," replied the man. And then the following questions and responses followed in quick succession:— "Read and write?" "Yes." "Ever here before?" "Oh, no!" "Trade?" "Clerk." "What were you tried for?" "Embezzlement." "That will do, you can go back," said the officer; and then turning to the entering clerk, he added, "with hard labour." As the prisoner heard this addition, he stopped at the door and remarked, "I thought it was without labour;" but the officer dispelled his hopes by repeating, "with hard labour."

All the prisoners had to answer to similar questions, all equally short, but often the replies were long, and a kind of cross-examination was required before a decisive answer could be elicited.

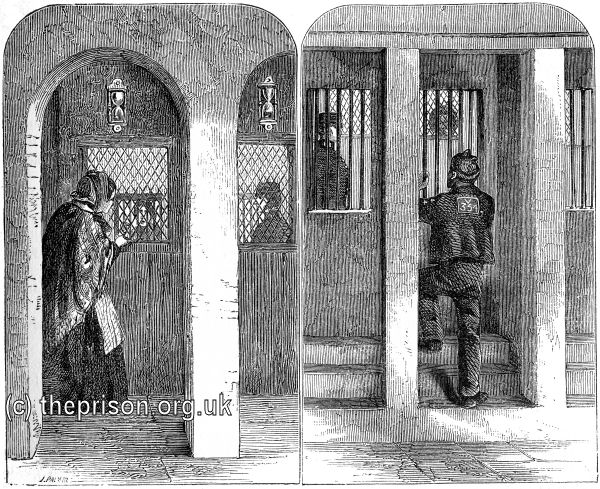

Presently we had an opportunity of being present during the visits paid to the prisoners by their friends. "Two relations or respectable friends," say the prison rules, "may visit a prisoner, in the presence of an officer, at the end of every three months, between the hours of ten and twelve."

All prisoners, on entering Coldbath Fields, cease to be called by their names, but are christened with a number instead. When a relation or friend calls at the jail on the day appointed for visiting, the criminal is asked for by the number he bears.

There are two arrangements in Coldbath Fields by which the prisoners are permitted to see their friends. The one is at the double gate before the building, situate between the entrance doors and the main prison, and the other is at a place built for the purpose in the first yard of the vagrant jail. At the latter a series of niches have been built in the side wall, each one just large enough for a man to enter. Through gratings the prisoners can converse with their visitors, who stand in almost similar niches, separated by a long passage, where a warder patrols. The gratings before the visitors are almost as close as net-work, in order to prevent anything being passed to the inmates of the jail. Only fifteen minutes are permitted for each interview, and, for the correct measurement of the length of the visit, hour-glasses are fastened up over the niches appropriated to the prisoners.

Visiting niches at Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

Prisoners' Letters.

All letters sent by the prisoners to their friends are opened by the governor before they leave the jail, to see that they contain nothing but matters relating to the family or personal business of the writer. Some of the men, knowing that their epistles are sure to be perused by the governor, endeavour, as is usual at other prisons, to win his good opinion, by giving to their compositions a religious and repentant air, in the hope of easing their labours and bettering their position.

Prisoners are not permitted to send or to receive more than one letter in every three months, but events of importance to prisoners may be communicated by letter (prepaid) to the GOVERNOR. Letters to or from prisoners are read before delivery; they should not exceed a sheet of letter paper, legibly written, and not crossed. They must contain nothing improper, and no detailed news of the day. Two relations or respectable friends may visit a prisoner, in the presence of an officer, at the end of every three months, between the hours of ten and twelve (Sundays excepted). The visit lasts a quarter of an hour. These privileges may be forfeited by misconduct. No clothes, books, or other articles, are admitted for the use of prisoners except postage stamps or money.

Of "Hard Labour" and "Prison Labour".

At the correctional prisons, labour, especially of the kind called "hard," forms part of the punishment to which the prisoners are condemned. Out of the 7,743 persons passing through Coldbath Fields in the course of last year, 4,511, or rather more than 58 per cent., were, according to the official returns, employed at "hard labour."

Men sentenced to hard labour at Coldbath Fields are employed at:

- Tread-wheel work.

- Picking Oakum (3½ lbs. daily).

- Cleaning

- Crank Work.

- Mat Making

- Tailoring.

- Shot Drill.

- Washing.

There are likewise other handicrafts, to which the men are put after they have been in the prison for some time, provided their behaviour has been good.

The Tread-wheel.

There are six tread-wheels at Coldbath Fields, four in the felons' and two in the vagrants' prison. Each of these is so constructed, that, if necessary, twenty-four men can be employed on it; but the present system is for only twelve men to work at one time. At the end of a quarter of an hour these twelve men are relieved by twelve others, each dozen hands being allowed fifteen minutes' rest between their labours. During this interval the prisoners off work may read their books, or do anything they like, except speak with one another.

Each wheel contains twenty-four steps, which are eight inches apart, so that the circumference of the cylinder is sixteen feet. These wheels revolve twice in a minute, and the mechanism is arranged to ring a bell at the end of every thirtieth revolution, and so to announce that the appointed spell of work is finished. Every man put to labour at the wheel has to work for fifteen quarters of an hour every day.

Those who have never visited a correctional prison can have but a vague notion of a tread-wheel. The one we first inspected at Coldbath Fields was erected on the roof of the large, cuddy-like room where the men take their meals. The entire length of the apparatus was divided into twenty-four compartments, each something less than two feet wide, and separated from one another by high wooden partitions, which gave them somewhat of the appearance of the stalls at a public urinal. The boards at the back of these compartments reach to within four feet of the bottom, and through the unboarded space protrudes the barrel of the wheel, striped with the steps, which are like narrow "floats" to a long paddle-wheel.

Tread-wheel at Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

When the prisoner has mounted to his place on the topmost step of the wheel, he has the same appearance as if he were standing on the upper side of a huge garden-roller, and some what resembles the acrobat we have seen at a circus, perched on the cask that he causes to revolve under his feet.

There are 24 steps in the wheel. The steps are 8 inches distant from each other. This gives 16 feet as the circumference of the wheel. The wheel performs 30 revolutions in each¼ of an hour. And therefore each man on it ascends 480 feet in of an hour. Each man works altogether 15 quarters of an hour a day. And so ascends in all 7200 feet or very nearly 1 mile 3 furlongs [2.19km] per diem.

All the men work with their backs toward the warder, supporting themselves by a hand-rail fixed to the boards at the back of each compartment, and they move their legs as if they were mounting a flight of stairs; but with this difference, that instead of their ascending, the steps pass from under them, and, as one of the officers remarked, it is this peculiarity which causes the labour to be so tiring, owing to the want of a firm tread. The sight of the prisoners on the wheel suggested to us the idea of a number of squirrels working outside rather than inside the barrels of their cages.

Only every other man, out of the twenty-four composing the gang on the wheel, work at the same time, each alternate prisoner resting himself while the others labour. When we were at the prison, some of those off work, for the time being, were seated at the bottom of their compartments reading, with the book upon their knees; others, from their high place, were looking listlessly down upon some of their fellow-prisoners, and who were at exercise in the yard beneath, going through a kind of "follow my leader" there. In the meantime, those labouring in the boxes on the wheel were lifting up their legs slowly as a horse in a ploughed field, while the thick iron shaft of the machinery, showing at the end of the yard, was revolving so leisurely, that we expected every moment to see it come to a stand-still.

Whilst we were looking on, the bell rang, marking the thirtieth revolution, and instantly the wheel was stopped, and the hands were changed. Those whose turn it was to rest came down from the steps with their faces wet with perspiration and flushed with exercise; while the others shut up their books, and, pulling off their coats, jumped up to their posts. There they stood until, at the word of command, all the men pressed down together, and the long barrel once more began to turn slowly round.

We inquired if the work was very laborious, and received the following explanation."You see the men can get no firm tread like, from the steps always sinking away from under their feet, and that makes it very tiring. Again, the compartments are small, and the air becomes very hot, so that the heat at the end of the quarter of an hour renders it difficult to breathe."

We were also assured that the only force required to move the tread-wheel itself is that necessary to start the machine, and that when once the regulator, or fan, begins to revolve, scarcely any exertion is necessary to keep it in motion. Nevertheless, the power that has to be continually exercised, in order that the prisoners may avoid sinking with the wheel, is equal to that of ascending or lifting a man's own weight, or 140 lbs.; and certainly the appearance of the men proved that a quarter of an hour at such work is sufficient to exhaust the strongest for the time being.

Another proof of the severity of the tread-wheel labour is shown by the subterfuges resorted to by the men as a means of getting quit of the work; either they feign illness or else maim the body, in order to escape the task. In the course of last year, according to the surgeon's printed report, there were no less than 3,972 such cases of" feigned complaints."

"We were compelled," writes Mr. Chesterton, the late governor, "to limit the quantity of water, otherwise many would drink it to excess, purposely to disorder the system. like manner did we narrowly watch the salt, else inordinate saline potations would be swallowed, expressly to derange the stomach. Soap would be 'pinched' (i.e., a piece would be pinched out), and rolled into pills, in order to found the plaint of diarrhoea. white would be applied to the tongue, and any available rubbish bolted to force on a momentary sickness. Daring youths, who winced not at pain, were constantly in the habit of making 'foxes' (artificial sores), and then, by an adroit fall, or an intentional contact with the revolving tread-wheel, would writhe and gesticulate to give colour to their deception.

The Tread-wheel Fan.

As we were leaving the gate we caught sight, for the first time, of an immense machine situated in the paved court, which leads from the main or felons' prison to that of the vagrants'. In the centre of a mound, shaped like a pyramid, and whose slate covering and lead-bound edges resemble a roof placed on the ground, stands a strong iron shaft, on the top of which is a horizontal beam some twenty feet long, and with three Venetian-blind-like fans standing up at either end, and which was revolving at such a rapid pace that the current of air created by it blew the hair from the temples each time it whizzed past.

Tread-wheel regulating fan at Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

This is what is called the regulator of the tread-wheel. By this apparatus the resistance necessary for rendering the tread-wheel hard labour is obtained. Without it no opposition would be offered to the revolutions of the wheel; for, as that power is applied to no useful purpose, the only thing which it is made to grind is, as the prisoners themselves say,"the wind." Another method of increasing the resistance of this "regulator" consists in applying to it the apparatus termed by engineers a "governor." If the regulator revolves too quickly, the governor, similar in action and principle to that of a steam-engine, flies open from the increased centrifugal force, and by means of cog-wheels and levers closes the fans at the end of the beams, thus offering a greater resistance to the air, and, consequently, increasing the labour of the prisoners working at the wheel.

Crank-labour.

Sometimes a prisoner, tired of working at the tread-wheel, or fatigued with the monotony of working at his trade as a tailor or cobbler, will complain of some ailment, such as pains in the back or chest, thereby hoping to obtain a change of labour. In such instances the man is sent to the surgeon to be examined. If he be really ill, he is ordered rest; but if, as often happens, he is "merely shamming," then he is sent back to his former occupation. Should he still continue to complain, he is set to crank-labour, and it is said that after a couple of days at this employment, the most stubborn usually ask to return to their previous occupation.

Crank-labour consists in making 10,000 revolutions of a machine, resembling in appearance a "Kent's Patent Knife-cleaner," for it is a narrow iron drum, placed on legs, with a long handle on one side, which, on being turned, causes a series of cups or scoops in the interior to revolve. At the lower part of the interior of the machine is a thick layer of sand, which the cups, as they come round, scoop up, and carry to the top of the wheel, where they throw it out and empty themselves, after the principle of a dredging-machine. A dial-plate, fixed in front of the iron drum, shows how many revolutions the machine has made.

It is usual to shut up in a cell the man sent to crank-labour, so that the exercise is rendered doubly disagreeable by the solitude. Sometimes a man has been known to smash the glass in front of the dial-plate and alter the hands; but such cases are of rare occurrence.

As may be easily conceived, this labour is very distressing and severe; but it is seldom used, excepting as a punishment, or, rather, as a test of feigned sickness. A man can make, if he work with ordinary speed, about twenty revolutions a minute, and this, at 1,200 the hour, would make his task of 10,000 turns last eight hours and twenty minutes.

Shot-drill

This most peculiar exercise takes place in the vacant ground at the back of the prison ,where an open space, some thirty feet square and about as large as a racket-court, has been set aside for the purpose, on one side of the plantations of cabbages and peas. There is no object in this exercise beyond that of fatiguing the men and rendering their sojourn in the prison as unpleasant as possible.

The shot-drill takes place every day at a quarter-past three, and continues until half past four. All prisoners sentenced to hard labour, and not specially excused by the surgeon, attend it; those in the prison who are exempted by the medical officer wear a yellow mark on the sleeve of their coat. Prisoners above forty-five years of age are generally excused, for the exercise is of the severest nature, and none but the strongest can endure it. The number of prisoners drilled at one time is fifty-seven, and they generally consist of the young and hale.

The men are ranged so as to form three sides of a square, and stand three deep, each prisoner being three yards distant from his fellow. This equidistance gives them the appearance of chess-men set out on a board. All the faces are turned towards the warder, who occupies a stand in the centre of the open side of the square. The exercise consists in passing the shot, composing the pyramids at one end of the line, down the entire length of the ranks, one after another, until they have all been handed along the file of men, and piled up into similar pyramids at the other end of the line; and when that is done, the operation is reversed and the cannon balls passed back again. But what constitutes the chief labour of the drill is, that every prisoner, at the word of command, has to bend down and carefully deposit the heavy shot in a particular place, and then, on another signal, to stoop a second time and raise it up

After a while the prisoners began to move more slowly, and pay less attention to the time, as if all the amusement of the performance had ceased, and it began to be irksome. One, a boy of seventeen, became more and more pink in the face, while his ears grew red. The shot is about as heavy as a pail of water, and it struck us that so young a boy was no more fitted for such excessive labour than prisoners above the age of forty-five, who are excused.

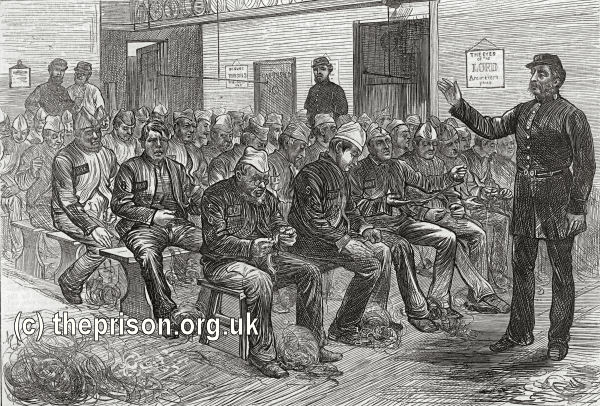

Oakum Picking.

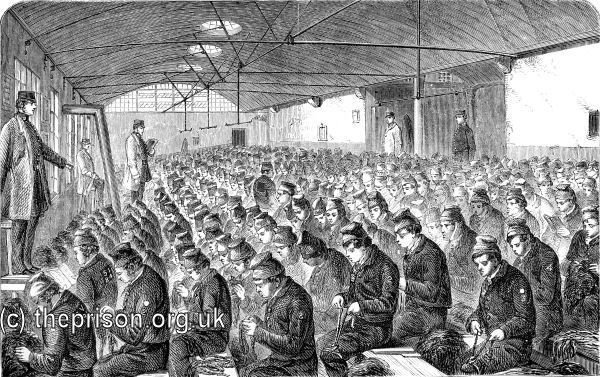

There are three distinct rooms where the prisoners pick oakum, one in the misdemeanour prison, and the two others in the felons' prison. We shall choose for our description the larger one in the felons' prison. It has lately been built on so vast a plan that it has seats for nearly 500 men. This immense room is situated to the west of the main or old prison, close to the school-room. It has a corrugated iron roof, stayed with thin rods, spanning the entire erection. We were told that the extreme length is 90 feet, but that does not convey so good a notion of distance to the mind as the fact of the wall being pierced with eight large chapel windows, and the roof with six skylights. Again, an attendant informed us that there were eleven rows of forms, but all that we could see was a closely-packed mass of heads and pink faces, moving to and fro in every variety of motion, as though the wind was blowing them about, and they were set on stalks instead of necks.

Oakum-picking at Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

If a man rest over his work for a moment and raise his head, he sees, hung up on the white walls before him, placards on which texts are printed. One is to the effect that "It is GOOD FOR A MAN TIAT HE BEAR THE YOKE IN HIS YOUTH;" another tells the prisoners that "GODLINESS WITH CONTENTMENT IS A GREAT GAIN;" whilst a third counsels each of them to "GO TO THE ANT, THOU SLUGGARD, CONSIDER HER WAYS, AND BE WISE.

The utter absence of noise struck us as being absolutely terrible. The silence seemed, after a time, almost intense enough to hear a flake of snow fall. Perfect stillness is at all times more or less awful, and hence arises a great part of the solemnity of night as well as of death.

The quantity of oakum each man has to pick varies according to whether he be condemned to hard labour or not. In the former case the weight is never less than three, and sometimes as much as six, pounds; for the quantity given out depends upon the quality of the old rope or junk, i.e., according as it is more or less tightly twisted. The men not at hard labour hare only two pounds' weight of junk served out to them.

Each picker has by his side his weighed quantity of old rope, cut into lengths about equal to that of a hoop-stick. Some of the pieces are white and sodden-looking as a washer woman's hands, whilst others are hard and black with the tar upon them. The prisoner takes up a length of junk and untwists it, and when he has separated it into so many cork screw strands, he further unrolls them by sliding them backwards and forwards on his knees with the palm of his hand, until the meshes are loosened.

Then the strand is further unraveled by placing it in the bend of a hook fastened to the knees, and sawing it smartly to and fro, which soon removes the tar and grates the fibres apart. In this condition, all that remains to be done is to loosen the hemp by pulling it out like cotton wool, when the process is completed.

When the men had fallen into line, and been marched off to their different yards, we inquired of one of the warders if oakum-picking was a laborious task. "Not to the old hands," was the answer. "We've men here that will have done their three or four pounds a couple of hours before some of the fresh prisoners will have done a pound. They learn the knack of it, and make haste to finish, so as to be able to read; but to the new arrivals it's hard work enough; for most thieves' hands are soft, and the hard rope cuts and blisters their fingers, so that until the skin hardens, it's very painful."

The quantity of rope picked into oakum at Coldbath Fields prison would average, says the governor, three and a half tons per week, which, at the present price of £5 the ton, would produce the sum of £ 17 10s.

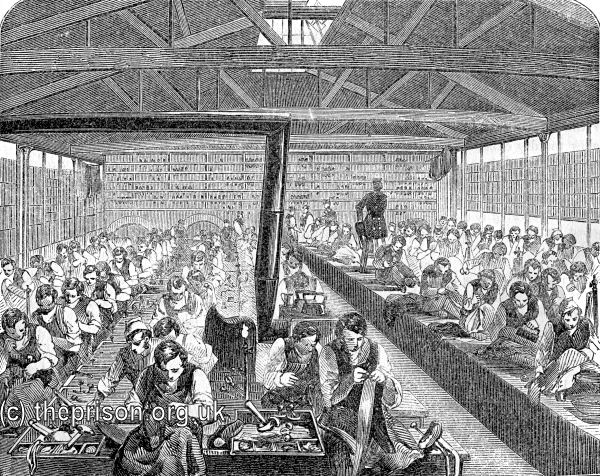

The Tailors' and Shoemakers' Room.

When a prisoner is brought to the House of Correction, he has the option given him — provided he was not sentenced to hard labour — of picking oakum or working at a trade. Through this arrangement the establishment boasts of a numerous staff of tailors and shoemakers, who have a large room, as big as a factory floor, given up to them, where, under the inspection of three officers, 160 of them pass the day, making and repairing clothing and boots and shoes. After the depressing sight of the tread-wheel yards and the shot-drill, it is quite refreshing to enter this immense workshop, and see the men employing their time at an occupation that is useful, and (judging from the countenances of the men) neither over-fatiguing nor degrading.

Tailors at Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

One entire side of this workshop is occupied by a raised platform, on which are seated a crowd of tailors, all with their shoes off, and cross-legged, like so many Turks. Tall rows of gas-lights stand up amongst them, most of which are, now that it is summer-time, serving as convenient places for hanging thick skeins of thread upon, or as pegs to sup port some unfinished work. The men have a certain grade in their work, beginning with repairing the clothes of their fellow-prisoners, then passing to the making of new suits of gray and blue for the future arrivals, and at length reaching the proud climax of working upon the cloth uniforms of the officers. When there is a lack of employment, some of the younger hands are set to work at shirt-making.

The earnings of the prison tailors are estimated at from 3d. to 5s.(!) the day, according to their proficiency, the lads who are just learning to use their needle being put down at a merely nominal sum — the value of everything made in the prison being estimated at what it would cost if the work had been paid for outside the prison. A great quantity of the clothes, boots, and shoes, sent to Hanwell Lunatic Asylum and the House of Detention, are manufactured at Coldbath Fields. A considerable portion of the "estimated profit of work or labour done by the prisoners," given in the annual returns, is earned in this large chamber.

The men bend over their work, silent as mussulmen at their devotions, so that the first impression on seeing the hands moving about is, that they are the gesticulations of so many dumb men.

The other side of the room is, however, not so quiet; for the eighty prison cobblers, seated on rows of forms, are hammering on their lapstones or knocking in the sprigs. The men wear big leathern aprons, like smiths', and some of them, with the last between their knees, are covering it with the dead black skin, pulling it out with nippers until you expect to see it split, and then tacking it down into its place. Others are bending forward, and screwing up their mouths with the exertion of making the awl-holes round the tough brown soles. Others, again, are throwing their arms wide open as they draw out the waxed threads. Two or three lads, working near the wall, are rubbing some newly-finished boots up and down with a piece of wood, as though they were burnishing the well-tightened calf and foot.

The Printing-office and Needle-room.

To see the printing-office, where the prison lesson-books are set up in type and worked off, we had to leave the main prison and cross over to that for misdemeanants. We found the prison printers sharing the same room with the "needle-men," for as there is not more typographical work required than will keep three "hands" employed, a separate workshop cannot be spared, so valuable is every bit of space at Coldbath Fields.

When female prisoners were sent to this jail, all the needle-work was performed by them; but since their removal to Tothill Fields the men have had to do the labour. The apartment, scarcely larger than a back parlour, was filled with the black-chinned needle-workers, who sat on forms, some darning old flannel-jackets, others making up bed-ticks. One, with a pair of spectacles almost as clumsily made as if they belonged to a diver's helmet, was"taking up" some rents in a mulberry-coloured counterpane, but he used his needle and thread somewhat after the manner of a cobbler making boots.

Against the wall of this needle-room stood a small printing-press, made so clumsily out of thick pieces of wood and unpolished iron, that there was no difficulty in telling that it had been manufactured in the prison. Close by was the frame on which was placed the case of types, with its square divisions for each letter, like the luggage-label trays at railways. In a side-room, we found the head printer busily folding up sheets of letter paper, with a newly-printed heading, on which the prisoners write whenever they send to their friends.

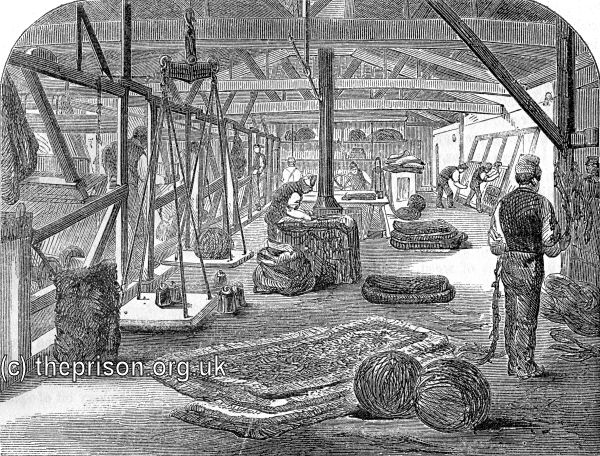

Mat-room.

Mat-making appears to be a favourite occupation with prison authorities; doubtlessly owing to the facility with which a man can be taught the occupation, and because such kinds of manufacture afford considerable occupation to others in preparing the different materials, "hands" being required, not only to pick the coir, but also to make the rough cordage for the mat; and in a jail labour is so plentiful, that the difficulty is to find sufficient employment for all the prisoners.

Mat room at Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

All the mats made at Coldbath Fields are contracted for by a wholesale dealer, who is allowed to place foremen over the prisoners, both to instruct the new, and superintend the old hands. There are thirty-three prisoners employed in the mat-room; but including those who dress the flax and coir, and spin the rope, occupation is afforded for about sixty hands.

It is a very peculiar sight to enter the large workshop set apart for the mat-makers, especially after leaving the adjacent oakum-room, where the silence of the junk-pickers is only broken by the sound of the moving arms; for the mat-room is alive with the clatter of tools and looms, and all the tumult of a busy workshop, so that the absence of all sound of the human voice appears to be the result of a close application to labour, rather than a prison punishment.

The big room, with its stone-paved floor, and iron-work roof, is as large as if a spacious yard had been covered in, and what with windows and sky-lights, it is almost as light as a photographer's studio.

The looms are used for manufacturing cocoa-nut fibre matting, and cheap hearth-rugs-a form of manufacture, which, compared with silk-weaving, is as different as house-carpenters' work is to cabinet-makers'. The gauze-like threads of the Spitalfields machine are replaced by coarse brown string; and the silk-weaver's shuttle, not so big as the hull of an ivory frigate, which darts with a whiz through the brilliant fibre of the Jacquard loom, is laid aside for one as big as a dressing-case boot-jack; and this had to be pushed and coaxed along the cordage that stretches across the beams like the strings of some coarse musical instrument. The battens come thumping down with a dead, heavy sound, while the muscles, swelling and moving in the bare arms of the weaver, show the exertion required to form the stiff coir into the required position.

The young men prisoners, seated at spinning-wheels, are rocking to and fro as they twirl round the humming disc that winds off the balls of coarse rope. The older hands are occupied with the harder work of making the rope door-mats; some plying a needle like a skewer, and others hammering with a wooden mallet to make the rows of the design lie evenly.

One of the boys was working at a stand fitted up with immense reels of crimson worsted, pulling off the threads so rapidly that the frayed edges threw out a bright-coloured smoke, which powdered his shoulders and the ground around as if the reflection of a painted window had fallen there. With this showy worsted the edges of the better kinds of mats are ornamented. The rug manufactory constitutes the fine arts department of the prison mat-room.

The overseer, anxious that we should see specimens of the work, called to a man who was clipping down the rough crop of a newly-made door-mat into a smooth lawn of fibre, and desired him to spread out some of the rolled-up rugs before us. "This one," explained the overseer, as we were looking at the rude design of a rose as large as a red cabbage, "is a cheap article, made mostly out of yarn; but here is the best style of goods we make," and another rug was spread out, with a full length tiger worked upon it.

Artisan Prisoners.

Printing, tailoring, shoemaking, and mat-making are not the only crafts which the prisoners are permitted to follow in Coldbath Fields. The whitewash on the walls has been laid on by prison plasterers; many parts of the prison have been erected by prison bricklayers and masons; the wood and iron work receives its annual coat of colour from prison painters; and even the tin mugs, out of which the men take their gruel, are manufactured by prison tinmen.

A list of the handicrafts pursued in the prison:

Plumbers.

Tinmen.

Bookbinders. Plasterers.

Glaziers.

Blacksmiths.

Basket-makers. Masons.

Sawyers.

Upholsterers.

Carpenters. Painters.

Coopers.

Education and Religious Instruction of the Prisoners.

The School-room.

As we were standing at the entrance of the felons' prison, a gentleman passed us dressed in black, and carrying under his arm a roll of what, from the marbled-paper coverings, were evidently copy-books. We instinctively asked if he were not the schoolmaster, and learnt that he was then on his rounds to collect together his class. The school hours commence at half-past seven in the morning, and end at half-past five in the evening. Each class consists of twenty-four scholars, and these are changed every hour. All the prisoners who are unable to read and write are forced to submit to instruction. We directed our steps to the westward portion of the main prison, where, in a kind of outbuilding, the classes are held.

The prison school-room is about the size of an artist's studio, being large enough to admit of twelve desks, arranged in four rows in front of the open space where the master's rostrum is placed. Each desk is sufficient for three scholars, but, to prevent talking, only two are allowed, one at each end, the middle place being kept vacant.

Against the whitewashed walls were hung maps as big as the sheets of plate-glass. Over the master's raised chair was an immense black board, with the letters of the alphabet painted in white upon it; whilst, to impress upon the "scholars" the necessity to be tidy, a printed maxim is hung between the windows, to the following effect:—"A PLACE FOR EVERYTHING AND EVERYTHING IN ITS PLACE."

Presently the pupils entered, in a long line, headed by the master. Each prisoner seemed to know his seat, for he went there as readily as a horse to his stall. All was silent as in a dumb asylum, the only sound being the rustling of the copy-books on their being distributed. A few minutes afterwards all the "pupils" were leaning over the desks, squaring out their elbows in every variety of position — some with their tongues poked out at the corner of the mouth, and others frowning with their endeavours to write well. It was a curious sight to see these men with big whiskers, learning the simple instruction of a village school. Some of them with their large fingers cramped up in the awkwardness of first lessons; others wabbling their heavy heads about as they laboured over the huge half-inch letters in their clumsy scrawl.

The schoolmaster is assisted in his duties by two prisoners, who, by their proficiency and good conduct, have been raised to the position of hearers — and to them the scholars repeat their lessons.

The books — of which there are three,from which the prisoners are taught are all printed and bound by prisoner workmen in the jail. In the first book the lessons are of the simplest form, beginning with the letters of the alphabet, then gradually comprising letters and words mixed up together, and concluding with short sentences. In the second lesson book one of the objects of the instruction is to make the pupils, by means of nonsense sentences, pay attention to the copy before them, for they are apt to read, we were told, only the commencement of a sentence, and jump at the meaning of the remaining portion. Accordingly these lessons are made into kinds of puzzles, like the following:— "train save thirst ring train thou shall soap save train pick thou." The third book contains lessons from the gospels; and by the time the scholar is able to copy out and read those correctly, his education, as far as the prison limit of reading and writing is concerned, is supposed to be completed.

Chapel.

The chapel is situate immediately over the entrance hall of the main or felons' prison. It is a kite-shaped, triangular building, seeming as if it were some spare corner of the prison that had been devoted to the purpose; the clergyman's place — for you can hardly call the little desk and arm-chair set apart for the minister a pulpit-being in a kind of small gallery at the apex of the triangle, and the seats for the prisoners below towards the base. Reckoning the seats in the gallery and on the ground, there is room for about 500 men.

The chapel is certainly a primitive and curious building. There are three compartments on the ground floor, and three in the gallery, separated from each other by a tall, strong, wooden partition, so that each storey presents somewhat the appearance of a huge three stalled stable. Instead of panelling in front of the men, as in other chapels, stout iron bars rise up, close set together, such as would be placed before an elephant's cage.

The governor, in lieu of a pew, has a comfortable arm-chair placed in the gallery, on one side of the chaplain's desk, and another row of arm-chairs is arranged as tidily as against a drawing-room wall, to receive visitors and the principal warders. Immediately under the gallery, on the ground floor, is the communion-table, and on one side of it hangs a notice-board, stating that "COMMUNICANTS DESIROUS OF PARTAKING OF THE SACRAMENT" must give due notice to the clergyman.

On entering the chapel, in company with the governor, we found the felon congregation already assembled, each cage being as closely packed with men as the gallery of a cheap theatre. On one side of the dirty-gray mass of prisoners, stood up the dark-uniformed warder. All the men had their caps off, showing every variety of coloured hair. There was one man, a big square-shouldered negro, whose white eyes, as he rolled them about, seemed like specks of light shining through holes in his dark skin; and we also observed a Malay, with his slanting eyes and dried mummy skin, whose long, straight hair hung from his pointed skull like the tassel on a fez. Nearly all the congregation appeared to be youths, for we could only here and there distinguish bald or white head. Some of these elderly sinners had spectacles on, and were busily hunting out in their Bible the lessons to be read that day. The building was silent as a criminal court when sentence is being passed.

When the prayer was ended, a sudden shout of "Amen" filled the building, so loud and instantaneous, that it made us turn round in our chair with surprise; the 500 tongues had been for a moment released from their captivity of silence, and the enjoyment of the privilege was evinced by its noisiness.

When the morning service had ended, the erring flock, under the guidance of the warders, left their pews in the chapel, and in a few moments afterwards were occupied with their different prison duties.

On Sunday all the men are taken to divine service once a day, part in the morning and the remainder in the afternoon; for the chapel in the felons' prison contains only 507 sittings, and that in the misdemeanants' prison but 274; and as the usual number of prisoners in the entire building is seldom below 1,300, of course only half of that number can attend service at one time. Those who are left behind are not, however, allowed to remain without religious instruction. Three men in each yard have been appointed by the chaplain to read aloud to their fellow-prisoners, and each relieves the other every half-hour. The book for the Sunday's reading is issued by the chaplain. It is of a purely religious character, and is usually "The Penny Sunday Reader," containing short sermons. Tracts are also distributed in the different yards, so that those who prefer reading to themselves, instead of listening to what is being read aloud, may do so.

The Prison Accommodation, Cells, and Dormitories.

The prison is capable of holding, altogether, 1,453 persons, and 919 of these can be accommodated with separate sleeping cells. The daily average number of prisoners in the year ending Michaelmas, 1855, was 1,388, while the greatest number at any one time during that year was 1,495; so that occasionally the prison contains three per cent. more than it has proper accommodation for.

Cells.

As regards the "separate sleeping cells," of which there are 919 altogether, they differ in size in each of the three different prisons, which make up the entire House of Correction. The largest are to be found in the old building, erected in 1794, and now set apart for felons; next in space come those appropriated to the vagrants, built in 1830; and the smallest ones are those situate in the misdemeanant's prison, constructed in 1832. We shall describe the cells we visited in the felons' prison, for these may be considered as the best form of the separate sleeping apartments in the entire establishment.

The cells are situate in the wings and corridors, on the first and second floors of the building, as well as on one side of all the eight exercising yards. The entrance to each cell is guarded by a narrow door, solid as that of a fire-proof deed-box, and just wide enough to allow a man to enter, whilst heavy bars and bolts make the fastenings secure. Every one of them is eight feet two inches long by six feet two inches broad, and has an arched groined roof springing from the sides, at an elevation of six feet, until it attains its highest pitch of ten feet. If it were not for the height of the apartment, the chamber would be about the size of an ordinary coal-cellar.

The walls and roof are brilliant with whitewash, so that one could almost imagine the cell to have been dug out of some chalk cliff, and the stone flooring has been holy-stoned until it is as clean as the door-step of a "servants' home." Fastened up to hooks set in the stone-work, and stretching across at the farthest end, is the hammock of cocoa-nut fibre, brown and bending as a strip of mahogany veneer, with the bed-clothes folded up in the counterpane rug, tightly as a carpet-bag. Hanging up against the wall are boards, on which are pasted printed forms of the morning and evening prayer, as well as "A Few Texts from the Bible." A wooden stool completes the furniture of the cell.

Over the door is a fanlight window, glazed inside, and protected without by heavy cross bars. In some of the cells another grated opening is let into the back wall. As we entered the cell it felt chilly as a dairy, so we asked the warder if it were not cold. "Not at all," was the answer. "In summer the men like being in the cells, in winter they prefer the dormitories." This desire on the part of the prisoners to quit the cells in winter, induced us to inquire whether, during the cold weather, the building were not heated by hot air or hot water-pipes. We were much startled to find that no such attention had been shown to the necessities of the wretched inmates. Again, seeing that no arrangements had been made for lighting the apartment with gas, we asked how the men managed for light in winter when, long before the locking-up time, the night has set in, and it is perfectly dark at the time of their entering the cells. We were informed that the men in the separate cells went to bed, although in the dormitories, where gas exists, they are allowed to remain reading until ten o'clock. Again, we found that no provision had been made to enable a prisoner to call for assistance in case he was taken ill during the night, and that his only chance of help under such circumstances, depended upon his ability to make sufficient noise to attract attention. Further, the ventilation of the chamber was most imperfect.

The prison authorities assert that the ventilation of the cells is sufficient and healthy. They point triumphantly to the extremely sanitary condition of the prison — the healthiest in London they say. In answer to this we urge that the House of Correction is a short sentence prison, where offenders are sent for terms averaging from three days to three years, and the returns do not admit of its being compared as to its daily average amount of sickness with that of other prisons.

The prisoners are locked up for twelve hours out of the twenty-four.

The prison authorities themselves do not offer a word of excuse for not lighting up the cells. In winter it is dark when the men are locked up in them, and it is dark when they rise, so that twelve hours are passed in total obscurity. Even some of the cells in the galleries are in summer so obscure that it is impossible to distinguish anything in them beyond the white washed walls.

As regards the defective arrangements for enabling the prisoners to call for assistance, if attacked by sickness in the night, we were told that a watchman patrols each prison, visiting every yard once in the half hour. Nevertheless, the fact of several sudden deaths having occurred in the cells demands, in our opinion, some such arrangements as exist at Pentonville.

It appears, however, that there is every probability of the prison being pulled down, a railway company, whose line is to pass through the building, having undertaken to erect another prison in lieu of the existing one.

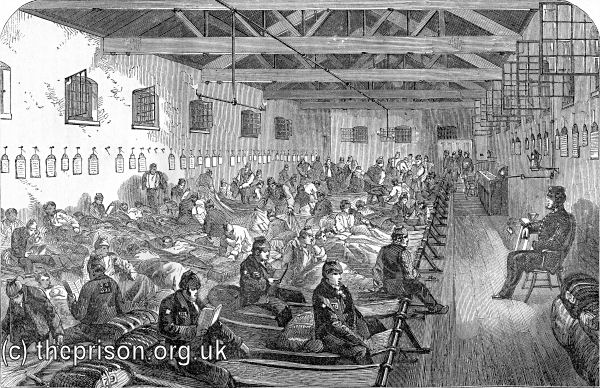

Dormitories.

By the aid of spacious sleeping-rooms the felons' prison, which contains only 356 cells, is made to accommodate 889 prisoners. There are altogether five such apartments at Coldbath Fields, all situate in the old portion of the building, and built on the same plan, the smallest capable of making up 82 beds, the largest 101.

The dormitories are eighty-three feet in length, and twenty-five feet broad; and if the pointed roofs, with their grained tie-beams, were more lofty, they would do very well for rude chapels. At one end are the lavatories, made out of slate, with a porcelain basin let into each of the ten divisions, the bright brass button showing that water is continually laid on.

The manner in which the hammocks are arranged is ingenious enough, for every inch of space is taken advantage of. Four stout iron bars, resting on supports a foot from the floor, run along the entire length of the building, the first next the passage, like a long thick curtain-rod just above the ground, and the others ranged at a distance of six feet from each other. To these bars the hammocks are suspended, so that three rows are obtained, while a passage of some five feet wide along one side of the room is still left for the warders to patrol up and down during the night.

Dormitory at Middlesex County Bridewell, Clerkenwell, London, c.1862. © Peter Higginbotham

During the day-time, when the bed-clothes are folded up into a close bundle, and the brown cocoa-nut fibre of the hammocks is visible, the rows of tightly-stretched beds attached at either end to the long iron bars seem interminable. They form a kind of raised plat form, gradually slanting upwards to the wall, as if they were so many sacks that had been carelessly laid across the rails.

Here, hanging against the wall, is a line of printed forms of the morning and evening prayers, ranged like the slates in a school-room.

The men lie with their heads to each other's feet, and, being near the ground, the warders, on their raised stools, can command a bird's-eye view of all the sleepers. The sides of the hammocks curl round the prisoners' forms, so that they look like so many mummies ranged along three deep.

Close to where the warders sat were two rings of gas burning beneath tin pots, from which issued the curling steam of the coffee allowed for the officers' refreshment through the night.

As we peeped, at a later hour, through the little inspection-hole in the closed door of the dormitory, we could see those who were conversing together. One of the men was lying flat on his back, with his handkerchief raised to his mouth, and though the eye on the side towards the warder was shut as if in sleep, the other one was wide open, and kept on winking at his apparently slumbering neighbour, in a manner which showed that the two men were having a nice quiet chat together. There can, indeed, be no doubt that it is utterly absurd in a prison conducted on the silent system, with the special view of avoiding intercourse among the criminals, to herd together a hundred such men, and place them in exactly that position which is the most favourable for intercommunion.

The daily routine of discipline at the House of Correction, is as follows:

| 6.25 a.m. | The gun fires, and the prisoners rise. The officers for the day enter, are mustered, and examined in the outer yard. Cells are unlocked, and the prisoners counted in their yards. |

| 7.00 a.m. | Work commences. |

| 8.00 a.m. | Breakfast and exercise in the yards. |

| 9.15 a.m. | Prepare for chapel. |

| 9.30 a.m. | Service commences. |

| 10.00 a.m. | Go to work. |

| 2.00 p.m. | Dinner, and exercise in the yards. |

| 3.00 p.m. | Go to work. |

| 5.30 p.m. | Supper. |

| 6.00 p.m. | Commence locking up. |

Stars.

To induce the prisoners to conduct themselves with propriety during their stay in Coldbath Fields prison, the system of stars, as badges of good conduct, has been adopted; one of these is given for every three months during which a man has not been reported for misbehaviour. These badges are in the shape of a red star, which is stitched to the prisoner's sleeve. We were told that at one time there was a man in the jail who had gained eleven such stars. Half-a-crown is given for each of the good-conduct badges on the day the prisoner is liberated.

We inquired of one of the warders whether he considered that these rewards had any influence over the prisoners' reformation. He replied that he thought not, and indeed, that he considered the half-crowns given for them as so much money thrown away. "The best behaved men," he continued, "are the old offenders — those who have been imprisoned before; they know the prison rules and observe them. Do you see that man with four stars on his sleeve?" he added, pointing to a prisoner in the exercising yard; "you observe he has a greater number of badges than any here, and yet it is the third time he has been in jail, as you can tell by the white figure on his other sleeve."

Of the Different Kinds of Prisons and Prisoners, and Diet allowed to each.

Vagrants' Prison.

The Coldbath Fields House of Correction consists of three distinct prisons — one for felons, another for misdemeanants, and a third for vagrants. The latter building is situated at the south-western corner, on the Gray's-Inn-Lane side, and occupies the point of ground enclosed by the bending of the outer wall, as it turns down from Baynes Row into Phoenix Place.

On entering the principal gates, there is seen to the left, through the strong iron railings which enclose the paved court like a cage — towards the quarter where the fan for regulating the tread-wheel is revolving — a broad tower, built in the mixed styles of a chapel and a granary; for it has a half-ecclesiastic appearance, the windows being tall and arched; whilst the walls have become so weather-beaten, that the yellow plastering with which they are covered has turned white in places, seeming as if covered with flour. That tower is the central "argus"-like portion of the vagrants' prison.

This prison, which was built in 1830, is designed in the half-wheel form, with four wings radiating like spokes from the central building. Though at first only calculated to accommodate 150 prisoners, it has since been enlarged, so that it now contains 177 cells. The second and third yards each contain a tread-wheel.

The plan of this prison is of the ancient kind. On each side of the yards are ranged the cells, those in the ground floor opening into the exercising ground, whilst in the galleries, on the first and second floor, the cells are ranged on either side of the passage. The cell furniture here is similar to that allowed to the felons, and consists simply of bedding and a stool, whilst hanging to the walls are boards, on which are pasted forms of morning and evening prayer; the cells, themselves, however, are inferior to those of the felons' prison in respect to size, being one foot less in width and breadth; though in all other respects they are similar in style, and, like them, neither warmed, ventilated, nor lighted.

Attached to the vagrants' prison is a strong room or cell, for either unruly or lunatic criminals. It is larger than the usual cells, and instead of a door has a strong iron grating before it, through which the incarcerated man can look out into a kind of passage before him, and which also enables the warder to watch him without the necessity of unlocking the door. The day on which, accompanied by the governor, we visited this portion of the jail, a man had been placed here for attempting the life of one of the warders. Hearing Captain Colvill's voice, he rose up from the dark corner in which he had been seated, and, advancing to the grating, requested that he might be permitted to have a bath. This prisoner had stabbed one of the officers in the back with a knife stolen from a warder's locker. Had the Millbank tin knives, however, been in use at this prison, such an act could not have been perpetrated.

The offences which, according to law, fall under the denomination of vagrancy, are principally as follows:

- Begging or sleeping in the open air.

- Fortune Disorderly telling prostitution.

- Gaming.

- Indecent exposure of person.

- Leaving families chargeable.

- Incorrigible rogues convicted at sessions.

- Obtaining money by false pretences.

- Reputed thieves, rogues and vagabonds, suspected.

Judging by the returns from the Metropolitan unions and the mendicants' lodging-houses, as well as the asylums for the houseless, there is good reason to believe that there are 4,000 habitual vagabonds distributed throughout the Metropolis, and that the cost of their support annually amounts to very nearly £50,000. That vagrancy is the great nursery of crime we have said, and that the habitual tramps are often first beggars and then thieves, and, finally, the convicts of the country — the evidence of all the authorities on the subject goes to prove. Out of a return of 16,901 criminals in London that were known to the police in 1837, no less than 10,752, or very nearly two-thirds of the whole were returned as being of "migratory habits." Moreover, throughout England and Wales there was, between the years of 1840 and 1850, an average of 21,197 vagrants committed to prison every year, so that the gross vagabond population of the entire country may probably be taken, at the very least, at that number; whilst in every 100 summary convictions by the magistrates, throughout England and Wales, the number of persons committed as vagrants was no less than 28.9, and those as reputed thieves 23: 4, or, together, more than 50 per cent. of the whole.

Misdemeanants' Prison.

Facing the kitchen, at the Bagnigge Wells corner of the felons' prison lies that for the misdemeanants, so that the three distinct prisons are built on a kind of diagonal line, which stretches from the north-eastern to the south-western corner of the boundary wall, across the ground enclosed within it

The misdemeanants' prison is decidedly the handsomest of the three buildings. It is built of brick, with white stone copings to the windows, which give a liveliness to the brown tint of the front. In the centre is a handsome, comfortable-looking dwelling-house (the abode of the deputy-governor); on each side extends the two-storeyed wings, with the plain brick-work pierced by strongly bound, half-circular openings, whilst the entrance to the prison itself is through a kind of cellar-door, placed like an arch under the bridge formed by the double flight of stone steps which lead up to the deputy-governor's house.

The half-wheel style of architecture has likewise been adopted in the erection of this prison, the spokes forming four distinct wings. By excavating the ground, the architect has managed to make the building, which outside appears to have but two storeys, have, in the interior, three; and thus 386 cells have been obtained. All the wings converge to the centre building, with which they communicate by means of covered-in bridges, whose sides of rough unpolished glass give them a light and pleasing look.

In the first yard there is an extensive oakum-picking shed, capable of holding nearly 200 men; and close to it are the laundry and the washhouse.

The cells in the misdemeanants' prison are the smallest of all those in the House of Correction, for not only are they less by a foot, both in breadth and length, than those in the felons' building, but they are also one foot less in height. They, too, are neither warmed, well-ventilated, nor lighted.